Rape in the military

From 1998: Women who have suffered sexual assault in the Canadian Forces are speaking out

Share

This story was originally published in Maclean’s May 25, 1998 issue:

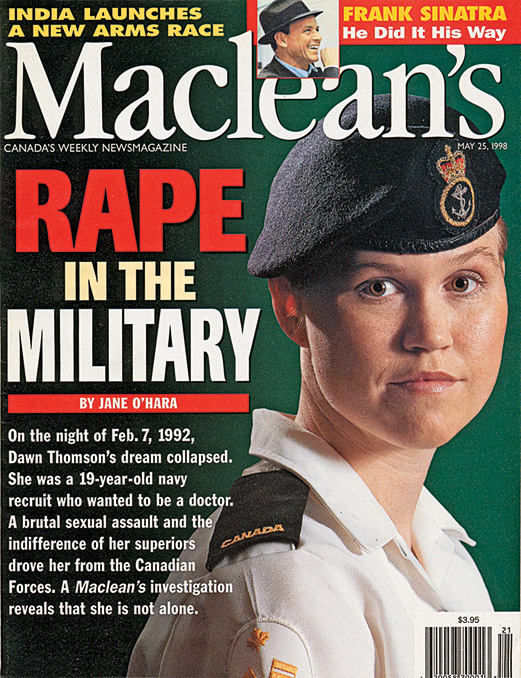

Dawn Thomson remembers peering up at the windows of Nelles Barracks when she arrived for her first posting at CFB Esquimalt in Victoria in January, 1992. She saw a wall of men’s faces—then came the hollering and the catcalls, a cacophony of sexual innuendo and gutter talk. “We were referred to as fresh meat more than once,” she noted in her diary. Back then, Thomson was a smart and smiling 19-year-old from Peterborough, Ont., anxious to start her naval signalman’s course at the Fleet School and hoping that, some day, the navy would put her through medical school. “I wanted to be somebody,” she says. The dream collapsed on the night of Feb. 7, when she awoke from sleep to find one sailor raping her and another—a man she considered a trusted friend—looking on laughing. “I was in his room,” she says. “He had brought me there because there’d been a big party and everyone was hammered. He said I’d be safer there than in my own room. I felt so betrayed.”

Related:

Speaking out on sexual assault in the military

Of rape and justice

She is not alone. Maclean’s has interviewed 13 women who say they were the victims of sexual assault in the Canadian military—and that their cases may represent a pattern of sexual harassment and assault of Canada’s servicewomen. Most of the incidents took place in the 1990s, after the military began its program of fully integrating women into the armed forces. And many of them reveal a systematic mishandling of sexual assault cases: investigations were perfunctory, the victims were not believed and often they—not the perpetrators—were punished by senior officers who either looked the other way or actively tried to impede investigations. And in the opinion of many of the women victims, the abuse they suffered is as shocking as the Somalia scandal, when members of the Canadian Airborne Regiment tortured and killed a Somali teenager in 1993.

The cases also reveal a culture—particularly in the navy and combat units—of unbridled promiscuity, where harassment is common, heavy drinking is a way of life, and women, who now account for 6,800 of the Canadian Forces’ 60,513 members, are often little more than game for sexual predators. Spokesmen for the department of national defence—which is now in the middle of a glitzy, $1.5-million campaign to entice more women into the Forces—say that recent efforts to deal with harassment have improved relations between the genders. Critics, though, say those efforts cannot eradicate a way of thinking that has existed for decades—and ease the situation of women in the Canadian Forces. Says one former member of the military police: “I knew male military police who made a game out of seeing how many new recruits they could nail in bed. They’d talk about it right at the front counter. What if they got caught? They didn’t care. They’d say, ‘Charge me. I’ll just lie.’ They became so accustomed to that phrase.”

In Dawn Thomson’s case, the Feb. 7, 1992, sexual assault was only the beginning of a traumatic experience. The next morning, crying, bleeding and in such pain she could barely walk, she was taken to the base hospital by a female friend. There, Lieut. Bonnie Henry, a doctor now retired from the Forces and working in San Diego, Calif., examined her for sexual assault, known in military jargon as the rape kit. In a department of national defence hospital emergency report dated Feb. 8, 1992, Henry wrote: “Rape kit obtained and physical exam conducted. MPs notified—kit turned over to Master Cpl. Rico Laidler.” After the exam, Thomson gave a statement to Laidler, the military policeman in charge of the investigation. The next day, Thomson called Laidler and the MP told her she had no case—that he believed her alleged assailants when they claimed she had willingly had sex that night. But a source close to the investigation told Maclean’s that the men later actually bragged openly about what they had done. “What they did to her was wrong, there’s no question about that,” says the source.

At 19, frightened and unsure of how the system worked, Thomson agreed not to press charges. Instead, she found herself on the receiving end: two weeks after reporting the rape, Thomson, back at Fleet School, was taken out of class, marched to the chief of Fleet School’s office and charged with being on the men’s floor after 11 p.m. It was information he had taken from her statement to Laidler. “They used my own complaint to charge me,” says Thomson, who was fined $250.

For 21 days, she was also confined to barracks—along with the man who she says assaulted her. Charged with having a woman in the men’s quarters after 11 p.m., he served his 21-day sentence in a room close to hers. For that time, she was forced to work alongside him and to stand beside him during roll call. Each day, the petty officers humiliated her further by ordering her to state publicly why she had been charged. “They were pretty much trying to drive me insane,” says Thomson.

Laidler, who is now a sniper instructor at a prison in British Columbia, defends his investigation—although he acknowledges that Thomson was badly bruised. And, he adds: “Her case was mishandled after it left me and went to her superiors, the guys in the upper echelons of the Fleet School.” He says he was appalled at her treatment. “That was wrong, the way they made her perform duties with that sailor and take that verbal abuse,” he says. “I complained about it to my superiors, but they said it was out of their hands.”

Even after the punishment, Thomson tried to soldier on. She underwent successful treatment for alcoholism, finished first among nine in her signalman’s course, and was transferred to CFB Halifax. But word of her attempt at whistle-blowing preceded her. According to Laidler: “Someone in Esquimalt called someone in Halifax and gave them a heads-up about her—and made her arrival worse.” Shortly after she arrived in Halifax, Thomson says, the harassment began again when one of her superiors warned: “I know about everything in Esquimalt. Don’t try pulling any of that here.”

For Thomson, now 25 and married, the treatment proved intolerable. She spent her final two months of service in the psychiatric ward at the military hospital in Halifax, suffering from a serious eating disorder and suicidal tendencies. She left the military on Sept. 9, 1993. Last month, still so emotionally fragile she cannot work, she won a lengthy battle with the Veterans Review and Appeal Board and was awarded a disability pension of $632 a month for her claim of post-traumatic stress disorder. It was, at the very least, a tacit admission that she had been grotesquely mistreated.

High-ranking officers and other military spokesmen say they take the issue of sexual assault seriously. “It’s a crime,” says Capt. David Marshall, who has been base commander at Esquimalt since 1997. “We just don’t tolerate it.” As for women who have been afraid to come forward, Cmdr. Deborah Wilson encourages them to “put their concerns on paper and address them to the chief of defence staff.” Wilson, who monitors gender issues at Defence headquarters in Ottawa, adds: “I would be very interested in hearing what went wrong for them.”

In an interview with Maclean’s, Defence Minister Art Eggleton said that his department had no sexual assault statistics. But, he acknowledged, “there are always individual cases—there is going to be some poor behavior.” Eggleton noted that new initiatives, such as anti-harassment programs, a new military investigative unit and a grievance board that operates outside the chain of command, will help solve whatever problems exist.

Those changes will do little to help those who have already suffered. Ruth Cummings, now a 26-year-old university student in Vancouver, still becomes visibly agitated when she recalls her experience. She was 21 when, on the night of June 18, 1993, she and her roommate were sexually assaulted by fellow sailor Eric Gervais in their room in the co-ed Stadacona barracks at CFB Halifax. A year later, Gervais pleaded guilty to the assault in a Halifax court and was sentenced to two years in prison. But in spite of the conviction, Cummings says her 24 months in the navy after the attack were a living hell.

Within 24 hours of the assault, she and her roommate returned to barracks to pick up some items from their room. There, they found Gervais’s underwear, watch and socks—evidence that should have been collected from the crime scene by the military police. While awaiting trial, Gervais was allowed to freely roam the base—and once threw rocks at Cummings’s roommate’s window in an attempt to get her to talk to him. Cummings and her roommate were posted to Esquimalt; shortly after, they were shocked to discover that Gervais had been posted to Esquimalt as well for training—the navy did not want to interfere with his career. Other humiliation followed: in Esquimalt, Cummings says, she was also called an “English slut” by francophone sailors who sided with the Quebec-born Gervais.

After finishing their training, Cummings and her roommate were posted to HMCS Annapolis—and quickly found their situation becoming even more intolerable. Cummings’s roommate grew increasingly disturbed when senior officers forced her to wake up the next watch—which entailed going into the men’s mess decks where some sailors often watched hard-core pornographic videotapes and others slept naked on their sheets. When she asked twice to be relieved of that duty, she was refused—by two different superiors. Finally, says Cummings, her roommate cracked and asked for a release from the navy. She followed suit in June, 1995. Her brother, Sean, an 11-year veteran of the Forces who vociferously supported her throughout the ordeal, also left the military in 1996. “It was horrible,” she says. “Everybody let us down.”

Of the women interviewed by Maclean’s, most were assaulted when they were most vulnerable, as raw recruits or recently minted privates in their late teens or early 20s—away from home for the first time, newly instilled with the fear of rank. Many have never really recovered. Some have suffered from nervous breakdowns and depression, others have developed eating disorders and tried to take their own lives. All have left the Forces, heartbroken that their careers were shattered and angry that the military response worsened their conditions.

That was certainly the experience of Catherine Newman. As a 27-year-old air force captain stationed in Qatar in March, 1991, during the Gulf War, she says she was ordered to attend a base party by Col. Romeo Lalonde, head of the Canadian Forces in the Gulf. Newman says that in a van on the way home from the party, a highly inebriated Lalonde put his hand down her blouse and up her skirt—while two other senior officers egged him on. Certain that her immediate superior would be supportive, she took her sexual assault complaint to him. Instead, she says, she was told that if she pursued the matter, she would be “on the next plane home as an administrative burden.”

Newman kept quiet. She waited two years, took a posting in Ottawa, and then filed her complaint. “I did it for other women,” says Newman, 33, who resigned from the Forces in 1994 and still lives in Ottawa. “Who else could? I had to come forward or it goes on forever.” At his 1994 court martial, Lalonde was found guilty of sexual harassment, fined $5,000 and demoted one rank. But his conviction was later overturned by the court martial appeal court on the grounds that the military judge had unfairly misinterpreted a statement that Lalonde had made about the incident. The appeal court said federal authorities were free to ask for a new trial—but they never did. The experience left Newman feeling bitter—and psychologically vulnerable. Now, the woman who once tossed grenades and fired machine-guns is afraid to answer her door or go to the mall. “I don’t go outside by myself any more,” she said. “I’m a changed person since the court martial. I found it as traumatic or worse than the assault.”

Experts say that military women who have been sexually assaulted by male colleagues may suffer greater psychological difficulties than civilians because of the special nature of the military. “The military was their family,” says Rick MacLeod, a lawyer with the Bureau of Pensions Advocates at the department of veterans affairs in Charlottetown. MacLeod, who has helped many assault victims fight for disability pensions, adds: “So, in many ways, these rapes were the same thing as incest. That’s why it might be more devastating than if it happens out on civvy street. That’s what bothers me more than anything about these cases.”

That devastation has hounded one woman, who will only be identified as former Cpl. B. Urlacher, for 13 years. In 1985, as a 19-year-old recruit, she was posted to CFB Borden—near the city of Barrie, Ont., 90 km north of Toronto and the largest training base in Canada —for a six-week course in administration. There, Urlacher says, she was raped by a soldier shortly after her arrival. She did not report it, fearing that her superiors would not listen—or that she would be made to look guilty. Besides, she says, there were other pressures to stay silent. “In the military, we’re trained to be teamworkers,” she notes. “It’s not right to tell on your teamworkers. So you keep it a secret.”

But the secret took its toll. In 1993—after repeatedly contemplating suicide—Urlacher tried to kill herself by overdosing on pills. She was taken to hospital; there, she told a psychiatrist about the rape. Urlacher, who subsequently left the Forces and now owns her own business on the Prairies, says she knows other women who were assaulted at Borden—and that warnings about the dangers of walking alone at night were commonplace. “We had to go out in groups of twos and threes and walk down the middle of well-lit streets,” says Urlacher. “We were told it was because too many women were getting raped.”

Many victims are now speaking out and seeking justice, talking to the courts and other tribunals to air their complaints and fight for compensation. In February, a federal judge in Toronto gave Kelly Scaglione, a former member of the military police, the go-ahead to sue the federal government for $12.6 million in damages. Scaglione had been in training at Borden in 1982 when she was raped by physical education instructor Master Cpl. Harold McLean. He pleaded guilty to the charge in a Barrie courtroom in 1997, and in a plea bargain, was sentenced to a three-month probation. (One former army instructor admitted that sexual relations between supervisors and recruits was common. He recalled that while at training camp in Cornwallis, N.S., he and others routinely had sex with young recruits. “That case is making a lot of us nervous,” he told Maclean’s about the McLean charge. “We’re looking over our shoulders.”)

Vancouver’s Cummings is also seeking a pension from Veterans Affairs. So far, she has been turned down three times; on Sept. 29, her case will be heard in a federal court in the Maritimes where it could determine the military’s legal responsibility for women who are raped while in the service. (Her roommate, who filed a disability claim arising from her sexual assault, received a pension of $648 a month last year and almost $16,000 in back pay.) At least three other women—all still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of being sexually assaulted by military personnel in the 1990s—have disability pension claims pending.

Civilians who have been assaulted by military personnel have also started coming forward. On Aug. 5, 1994, while employed as a bartender in A Club, the junior mess hall at Camp Borden, Jamie Monkman was sexually assaulted and beaten up by a soldier. An ambulance took her to a Barrie hospital where her injuries were evaluated. But although the military police were called in, Monkman felt they did not take her case seriously, and she was forced to hire a lawyer. The soldier was eventually charged by civilian authorities and entered into a peace bond, paying $500 and agreeing to stay away from Monkman for nine months.

Veterans Affairs lawyer MacLeod believes the recent spate of highly publicized sexual assault scandals in the American military may be one reason more Canadian women are now making themselves heard. “My feeling is that there are a lot more of these cases out there and that a lot more of them will come forward,” said MacLeod. “My clients all know other women who have gone through similar experiences.” And if the American experience is anything to go by, the numbers in Canada may end up being startling.

Since the Tailhook scandal of 1991—when 83 female officers claimed to have been abused at a convention of naval and marine pilots—the U.S. veterans affairs department has established an extensive network of sexual trauma programs, which include specially trained counselling teams at their medical and veterans centres and a sexual assault information line. Since 1992, veterans affairs counsellors have provided treatment for more than 22,000 military women whose complaints date back to the Second World War. “I don’t think anyone had anticipated these kind of numbers,” says Joan Furey, director of the department’s Center for Women Veterans in Washington. “A lot of these women kept it a secret. For them to finally have it come out and have people acknowledge that it happened is a tremendous relief.”

So far, the Canadian military has only one sexual trauma treatment program, at the Canadian Forces Support Unit Ottawa Health Care Centre. Over the past decade, the Canadian military has largely denied that a problem exists, maintaining that the incidence of sexual assault in the military is no greater than that in the civilian world. “We don’t have a statistical basis that would indicate that in the Canadian Forces this occurs more than it might in other places,” Eggleton told Maclean’s. But some bases have more of a problem than others. With its transient population of men and women on short-term training courses, CFB Borden is widely acknowledged to be one of the worst. In fact, from April, 1997, to March, 1998, Barrie’s Rape Crisis Line received 72 calls for help, all of them related to the military.

Anne Marie Aikins, executive director of the Barrie crisis line and past president of the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres, says that the hierarchical, patriarchal nature of the military makes women—especially those in the junior ranks—very vulnerable to sexual assault. “It’s a system where there are many levels of superiors and a lot of power is given to those superiors,” said Aikins. “So the lower you are, the less power you have and the less likely you are to have a voice. The less apt you are to speak out, the more people will be free to commit acts like this.”

Military strictures against speaking out make it difficult to get an accurate picture of the extent of sexual assaults within the Canadian Forces. But interviews with male military personnel—all requested anonymity for fear of reprisals—reveal a world in which assault is common. One former instructor at the basic training school in Cornwallis, N.S., said that sexual assaults of female students by instructors were routine—and were often hidden from the official record. “When guys would get caught,” said the soldier, “they were offered two choices. They could either take a commanding officer’s punishment—a fine and some extra duties—or they could take a court martial. But they were intimidated into taking the CO’s punishment because that way it would never be written down anywhere—the whole thing could be kept pretty quiet.”

One soldier who is still in the military told Maclean’s he was a witness to a rape on a military base in 1992. A superior officer, he says, insinuated that he would be charged with conduct unbecoming on some unrelated matter if he didn’t side with the perpetrator against the victim. “He didn’t directly order me to lie, he manoeuvred me there,” says the soldier. “It was like a chess game.” Another, also still in the Forces, says he has personal knowledge of two sexual assaults against women by a training officer who is still on the job. In one case, he says, the officer told a woman she would not pass her training course unless she had sex with him. “He came out of his quarters the next morning bragging about what he’d done,” says the soldier. “He said, ‘Oh she was a real good one. She does everything you want.’ ”

Another female private, he says, was raped, then driven out of the military by a campaign of intimidation—including misleading instructions about what military dress was required for functions—after she reported the assault to military police. “Over the period of a few months, she was continually given wrong orders, either about what dress to wear or what time to show up for duty,” says the soldier. “They don’t get rid of you by firing you. But if I tell you over a couple of months to come in at the wrong times and to wear the wrong dress, that will show in your personnel evaluation reports and your written warnings. That’s the administrative way they get rid of you.”

While most women say they anticipated some form of sexual harassment when they entered the military, few were prepared for the flagrant hostility they found. “We were referred to as splits because we have vaginas,” says one woman, who went through basic training at Cornwallis in 1990, but left the Forces two years later because she could no longer put up with the abuse. “We were taught that women who wanted to join the Forces were one of two things: sluts or lesbians. I tried to ignore it. I joined the military for a job—and I was good at my job. I finally said why the hell am I doing this?”

Vancouver’s Cummings describes an atmosphere of “drunken debauchery,” where officers preyed on young, naive subordinates—despite standing orders on all bases that outlaw such fraternization. “You go ashore and to the bar and your lieutenant or your captain or your master seaman or your petty officer starts sliming all over you when he’s drunk,” she says. “These people are higher than you and you don’t want to say or do the wrong thing. It happens continually.” Another female recruit who left the military in 1993 described instructors at the end of basic training handing out condoms by the dozen and telling the women to “have fun.”

It was, she says, “like they expected us to be wild animals and go out and sleep with the first thing we saw,” she says. “I think they should have had more respect for us.” Respect. In spite of the apprehensions, that is what Dawn Thomson and Ruth Cummings and many other women hoped for when they joined the military. Instead, as Thomson now notes sardonically, “they gave me three weeks of Prozac and a bus ticket home.” Now, she and others are speaking out, no longer content to endure in silence the memory of what they suffered.