New HIV strategy sets hopeful goal, amid grief of flight MH17 losses

In the shadow of the deaths of conference delegates, new strategies for combatting AIDS are debated

AFP/Getty Images

Share

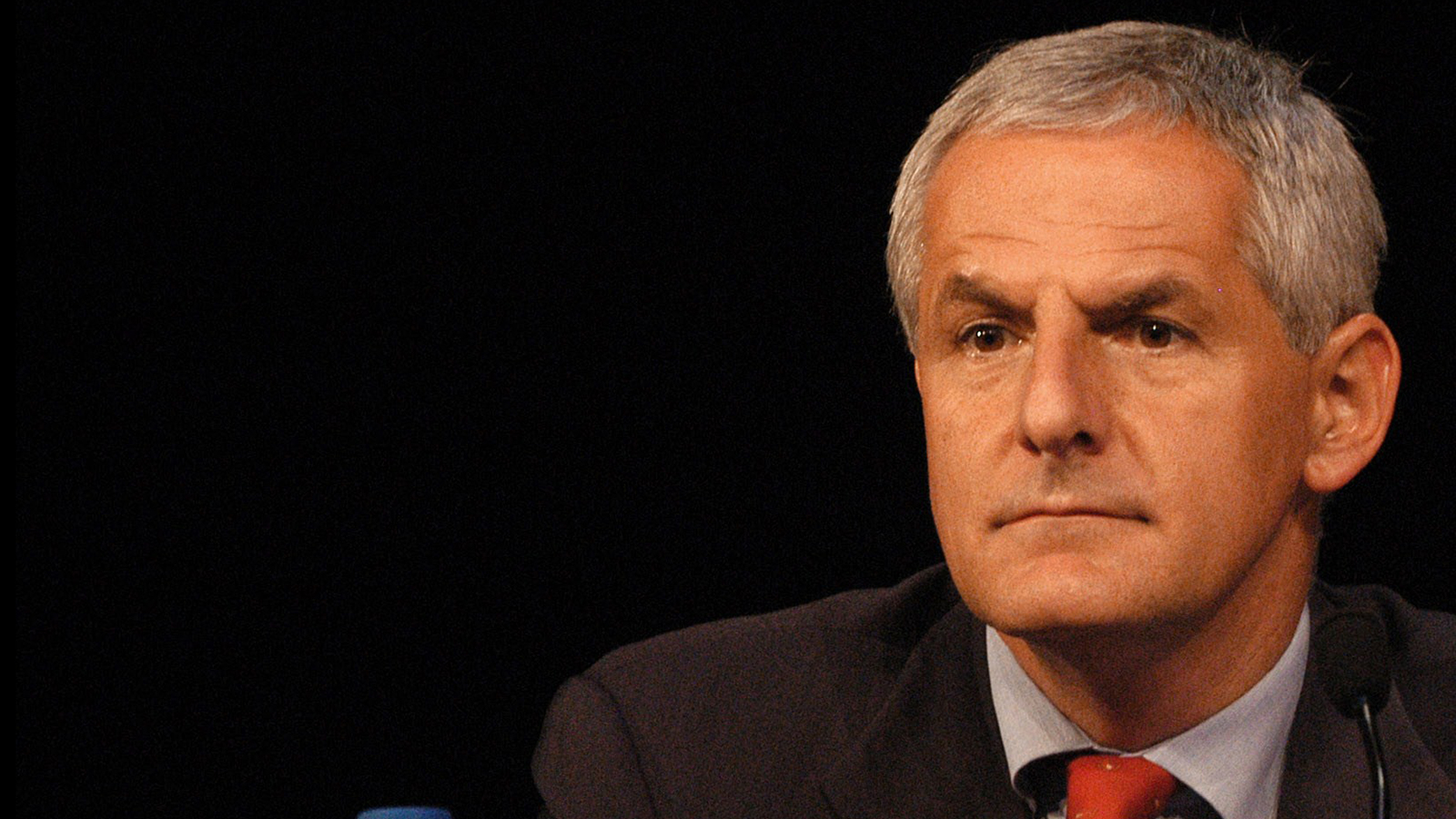

Dr. Julio Montaner, a top AIDS researcher and professor at the University of British Columbia, last saw his long-time friend and collaborator Dr. Joep Lange earlier this month. As special adviser to the United Nations on HIV/AIDS, Montaner had convened a high-level meeting to go over a new strategy for combatting AIDS worldwide—one being presented and discussed at the International AIDS Conference, in Melbourne, Australia, this week. “That is why I am here. It is why Joep was travelling to Melbourne,” says Montaner, who was deeply shaken after learning that the Dutch AIDS researcher was killed on July 17, when his Malaysia Airlines flight to Kuala Lumpur—en route to Melbourne—was shot down over eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 aboard, including at least six conference delegates.

The new strategy, called “90-90-90,” sets ambitious targets for combatting AIDS, and it comes at a critical time. With the UN’s Millennium Development Goals set to expire next year, researchers are looking beyond 2015. By 2020, the aim is to have 90 per cent of all people with HIV aware of their status. Further, 90 per cent of those diagnosed will receive regular antiretroviral therapy. And 90 per cent of people being treated will have lasting viral suppression. “This will open the door to an AIDS- and HIV-free generation,” says Montaner, who, like Lange, is a past president of the International AIDS Society (IAS). The UNAIDS paper outlining the strategy states bluntly: “[O]ur aim in the post-2015 era is nothing less than the end of the AIDS epidemic by 2030.”

Despite this hopeful message, the mood at AIDS 2014, as the conference is called, has, of course, been sombre. Held every two years, it attracts participants from around the globe. (This year’s number some 12,000.) “I go to many scientific meetings, but this one is always remarkable,” Dr. Marina Klein, a McGill University associate professor of medicine, told Maclean’s from Melbourne. “It’s the one where we bring together clinicians, scientists, activists and people living with HIV, who all learn from one another.”

Condolence books have circulated. The opening, on July 20, was marked by a moment of silence. Carmen Logie, assistant professor of social work at the University of Toronto, who has attended each year since 2008, says she’s received a flood of emails from concerned friends and colleagues. “This has touched every delegate,” Montaner says. He first learned that Lange and his partner, Jacqueline van Tongeren, might be on board the downed Malaysian plane through an email he received while awaiting a taxi to take him to the airport. “I tell you, it’s one of those moments I will remember forever.”

The fight against AIDS has seen significant progress since Lange and Montaner first started working together in the early ’90s. Today, HIV is increasingly a condition people live with, rather than die from. The UNAIDS discussion paper on 90-90-90 outlines how far we’ve come. Someone who acquired HIV in the “pre-treatment era,” it says, could expect to live 12½ years. Today, a young person in the developed world who becomes infected can live out a relatively normal lifespan. As of December, almost 12.9 million people worldwide were receiving antiretroviral therapy; at least 15 million should be receiving the same by 2015.

Challenges remain. “We have made fantastic progress,” acknowledges Dr. Mark Wainberg, director of the McGill AIDS Centre, and another past IAS president. “There are still many countries where we treat HIV, but we don’t do it with the best drugs. Joep would have argued, as we all do, that we want the best drugs to be available [to all].” As of December, the UNAIDS report notes, more than 60 per cent of all people living with HIV still lacked treatment, with spotty coverage in Africa (in sub-Saharan Africa, coverage is at 37 per cent; it’s 11 per cent in the Middle East and North Africa). Sharing information and other resources will help bring costs of treatment down, the report says; per patient costs decline as those with HIV receive regular treatment and require less intensive interventions. The 90-90-90 targets are realistic, Montaner says. “It’s done, proven, tested. This issue is, do we have the leadership to deliver on it?”

As this strategy is presented and debated at AIDS 2014, Lange’s absence is acutely felt. “Time will heal these huge scars,” Montaner says. “But the path is clear. The route has been described.” The end of AIDS is finally in sight, Montaner and others believe. It’s a fitting legacy for Lange, described by so many in Melbourne as a “giant of HIV medicine.”