Satire: Use at own risk

Brian Bethune on the long and uneven tradition of satire — from Swift to South Park to Charlie Hebdo

Share

Satire has always been celebrated in Western culture, even through the clenched teeth of those being satirized, for the moral outrage that propels it at its finest. In short, for often mythic reasons: the value of, say, South Park, which has been savagely mocking everything for two decades, is debatable for many, who see neither courage, nor beneficial outcomes nor actual moral fervour in it. Even in the case of English literature’s most famous satire, Jonathan Swift’s brilliant A Modest Proposal—which blandly suggests an obvious solution (eat the children) to 18th-century Ireland’s dual problems of starvation and overpopulation—the practical effects then and now are debatable. But as an ideal—the crusading artist, whether writer or illustrator, raging with a brave mockery that entertains and shames and changes hearts—the satirist is honoured. In some places, notably France, the satirist and the satirical vehicle, whether magazine or TV show, are perched on the higher rungs of the cultural ladder, almost sacred cows themselves.

It wasn’t always so. Celebrated or not, until relatively recently satire was a chancy business even in the West, its peril always in direct proportion to the sacredness, power and cruelty of the ox being gored. Criticism of medieval church prelates or Renaissance popes could lead to encounters with the Inquisition, and in pre-revolutionary France, Voltaire often found it prudent to live abroad. It’s also difficult to distinguish from pure mockery or simple political opposition — the mobs that attacked abolitionist newspapers in the antebellum South were not angered by satirical humour. Yet there is something in the real thing, a stinging truth that leaves the powerful naked and ridiculous, without any answer but repression. Satire also lodges in the popular consciousness with an afterlife that continues long after earnest protests are forgotten: there are endless historical accounts about the bureaucratic and deadly stupidity of armies, but none that will survive as long as the satirical novel Catch 22.

Related reading: Charlie Hedbo and the revenge of old religion.

In the past half-century, though, as ever-wider free expression became a core Western value — as long as libel laws and their modern offspring, hate-speech bans were skirted — satire offered little danger to its practitioners, who could attack virtually anyone in a culture with very little untouchable left in it. There was probably something of that thoughtless assurance in the offices of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which, in 2005, commissioned 12 cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad — even though the paper’s stated object was to test the limits of self-censorship in the wake of the murder of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh the year before, as well as what happened to Salman Rushdie in 1989, when Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill the British novelist for perceived blasphemies in his Satanic Verses novel.

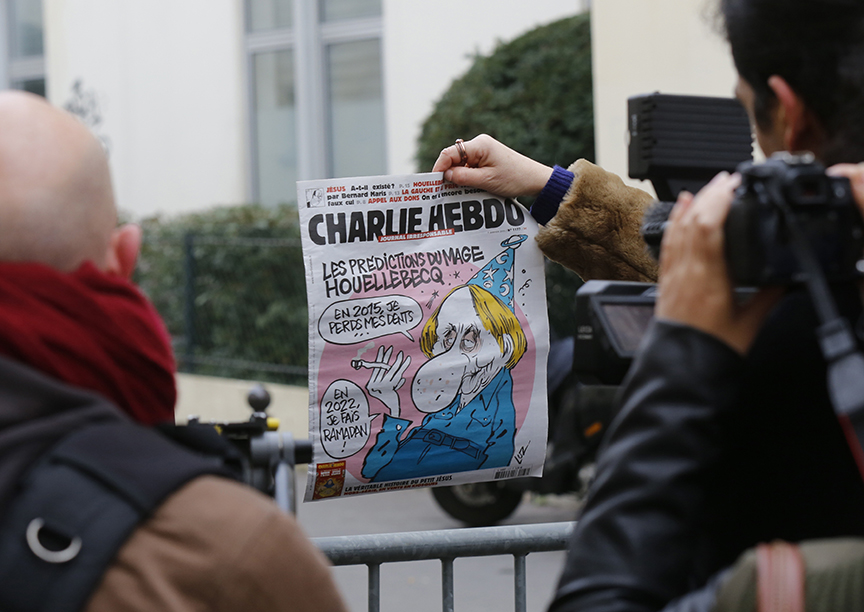

The reaction — riots worldwide causing more than 200 deaths, continuing threats and attacks on the cartoonists — marked the return, for the first time since the Nazis, of real physical danger for satirists. And it marked too, a resurgence — from those who did not self-censor themselves out of the fray — of the sort of courage and moral defence of free speech that originally brought political satire to the esteem it holds in our culture. It’s the sort of courage the staff of Charlie Hebdo, firebombed only three years ago, displayed in full awareness of the risk to their lives, a risk that caught up with them Jan 7. In a long and uneven tradition, their place of honour is unquestioned.

Related reading: Cartoonists pay tribute to Charlie Hebdo.