The most dangerous place in the world

On the Pakistan-India border, two nuclear powers are quiety edging closer to war

Share

It was a controversial move, the first of its kind in 15 years: On Sept. 11, the British Parliament held a debate on the ongoing crisis in Kashmir. What was odd about it was not only that the British parliamentarians would be discussing a bilateral issue between Pakistan and India, but that they would do it at a time when more important, seemingly urgent events were playing out elsewhere.

Islamic State had recently released videos showing the beheadings of two American journalists and were threatening to next kill a British aid worker (a threat it carried out on Sept. 13). The U.S. administration was in crisis mode, reaching out to its allies to form a united front against the group formerly known as ISIS.

Many people responded with bewilderment to the call made by one British parliamentarian, David Ward, for a debate on Kashmir. Even the moderate Indian press wondered why the British government would want to talk about a conflict with no obvious direct links to the U.K. Others condemned the British meddling in India’s internal affairs and accused Ward of acting like a colonial overseer. But the Liberal Democrat representative of Bradford, a city with a sizable Kashmiri population, had a crucial point to make: “With the rise of extreme jihadists and NATO forces leaving Afghanistan,” he said in the opening comments to the debate, “there is a real danger that . . . ‘unemployed jihadists’ will look for new opportunities within the unresolved Kashmir conflict.”

The point of the debate, he went on to say, was that while everyone has looked the other way, the world’s most dangerous conflict—one pitting two nuclear-armed neighbours against each other—has quietly edged toward catastrophe in recent weeks.

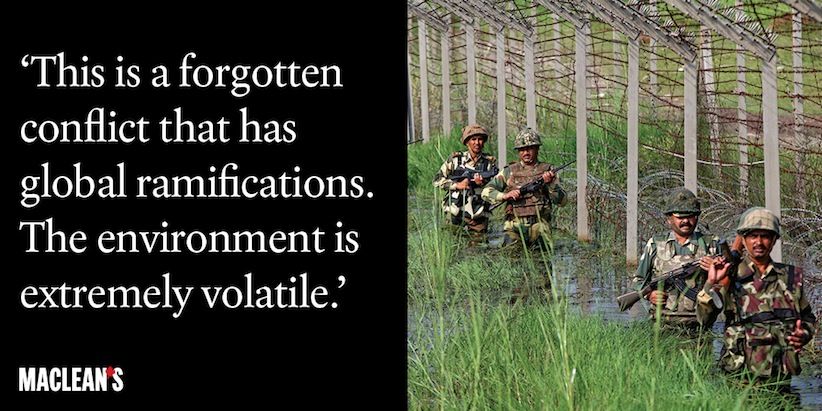

The signs are worrying: Cross-border shelling at the Line of Control, the de facto border separating Indian-held Kashmir from Pakistan, has spiked in recent weeks. India is again accusing Pakistan of facilitating the movement of militants, claiming it has captured dozens of fighters attempting to enter India and uncovered a 50-m-long infiltration tunnel.

Recent floods in Kashmir have further increased tensions. Natural disasters in Pakistan have always proven an effective recruitment tool for extremist groups such as the Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), a charity organization with links to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Pakistan’s most feared and powerful anti-India militant group. Its relief efforts often outstrip the government and are accompanied by propaganda campaigns that paint India as the cause of all the misery inflicted on Pakistanis.

“This is all India’s doing,” Muhammad Yassin, a 48-year-old farmer in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-held Kashmir, tells Maclean’s by telephone. “They have built dams on their side of the border and control the water flow of all the rivers. If there is flooding here, it is because India wants it.” Radical leaders like Hafiz Saeed, the founder of the LeT and current head of the JuD, have latched onto this sort of anger, claiming on Twitter that “India has used water to attack Pakistan,” and calling the floods “water terrorism.”

As ridiculous as it might sound, some Pakistanis believe it, highlighting the depth of the anger Pakistanis feel for their Indian rivals—an anger that has erupted into two wars (and nearly a third) over who has the right to control the Muslim-majority alpine region.

It’s the kind of hatred that fuels militant activities. Saeed, for instance, is back on Pakistan’s front pages after a long hiatus following the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai, blamed on the LeT. India claims he masterminded the bloodshed that left 164 dead and hundreds more injured and has demanded Pakistan prosecute him. Pakistan counters that Saeed has been exonerated by the courts and, according to a Sept. 15 statement by Pakistan’s ambassador to India, “is a Pakistani national” and “free to roam around.”

The implications of his freedom, and apparent revival of activities, herald some potential dark days to come. “The LeT is coming back to life,” says a former LeT fighter named Abdullah, who spoke on the condition that only his first name be published. “After Mumbai, they were told by Pakistani intelligence to freeze their activities. Now, my contacts say they have been given permission to resume their attacks.”

If the LeT is back, then Kashmir is heading toward disaster. “This is a forgotten conflict that has global ramifications,” says Ward in an interview. “You have two nuclear powers facing off against each other. The regional environment, including what’s happening in Palestine and Syria, not to mention Afghanistan, is extremely volatile. We need to be talking about this and formulating an international response.”

Back in the late 1980s, a similarly poisoned environment launched Kashmir into its worst years of conflict. Poor governance, including fraudulent elections in 1987, ignited an insurgency that quickly turned into a proxy war supported by Pakistani intelligence agencies that took advantage of the thousands of militants leaving the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan and pushed them across the border into India.

Now, history looks set to repeat itself, as recent developments have made the situation in Kashmir particularly dangerous. The war in Afghanistan is again approaching a critical phase with international forces exiting, freeing up thousands of experienced foreign fighters. Pakistan’s own fight against homegrown extremists, meanwhile, is showing signs of success. The Pakistani Taliban, a loose alliance of militant groups engaged in a bloody insurgency against the Pakistani state, is collapsing in the wake of a leadership struggle and an ongoing military offensive in North Waziristan. Factions have broken away and either announced allegiance to the Afghan Taliban or Islamic State, rejecting violence against the Pakistani state and promising instead to focus their efforts against “infidels” and “imperialists” in Afghanistan and Kashmir.

The political environment is equally unstable. Last spring, the Hindu nationalist BJP won a significant victory in India’s national elections, gaining majority control of Indian politics for the first time in its history. Its leader and now prime minister, Narendra Modi, is a hardliner with a history of treating India’s Muslims with disdain.

In the lead-up to the elections, Modi caused a stir by defending the BJP’s calls to abrogate article 370 of the Indian constitution, which guarantees special status for Kashmir, including broad powers of self-governance. He then stirred the pot some more following his election victory by announcing that the BJP would set aside $90 million to resettle the families of 62,000 Hindu pandits, or religious scholars, who fled Kashmir during the early days of the insurgency. Critics have argued that doing so will require a massive redeployment of Hindu soldiers into the valley.

Things don’t look much better on the other side of the border. Recent anti-government protests in Pakistan have weakened Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who won his own majority in Pakistan’s May 2013 elections with a promise to normalize relations with India. The powerful army, which considers itself the sole architect of Pakistan’s strategy toward its neighbour, wagged its finger and now appears to be fully back in control.

For Pakistan’s generals, the primary concern is finding a way to deal with the thousands of religiously motivated militants who could soon find themselves without a war to fight inside Pakistan. Their numbers are growing at an alarming rate alongside the growth of Islamic State. Sources in Pakistan’s Tribal Areas and in Peshawar, the capital of the restive northwest frontier bordering Afghanistan, say more and more locals are looking to Islamic State for guidance and inspiration.

“These are the same people who have fought the Pakistani army in the Swat valley and elsewhere,” says Nawab Khan, a local journalist in Peshawar who has covered militant activity in Pakistan for years. “They have been demanding sharia law for a long time, and they now see the Islamic State as their best chance to get it.”

Pakistan’s default solution is to send these extremists elsewhere, meaning the Kashmir jihad is back on the agenda. And that has the potential to ignite a conflict that will make Islamic State feel like a mere nuisance.