How powerful is the religious right in Canada?

Opinion: Various forces have made Canada’s Christian conservatives a weaker political group than America’s. Could that change?

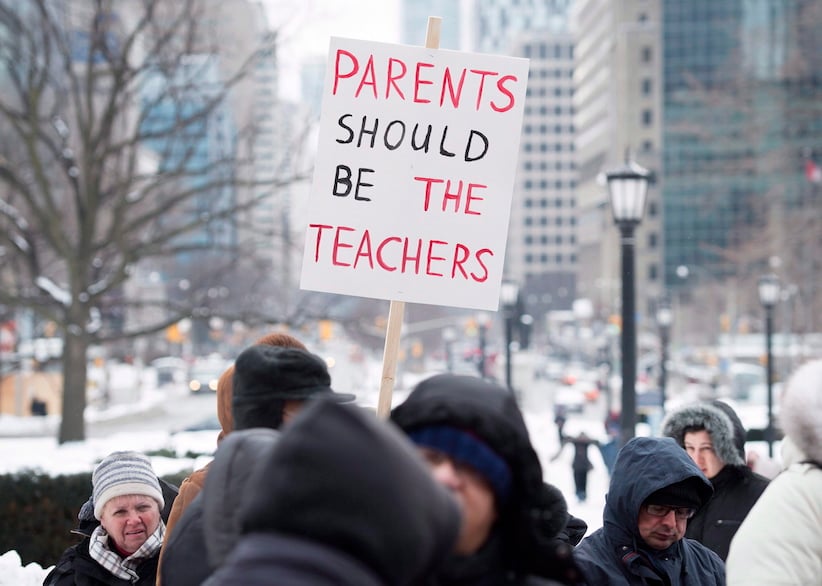

Demonstrators gather in front of Queen’s Park to protest against Ontario’s new sex education curriculum in Toronto on Tuesday, February 24, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darren Calabrese

Share

Michael Coren is a journalist and broadcaster and the author of 16 books.

It’s always comforting to assume moral superiority. The Greeks did it when they lost dominance over the ancient world to the Romans; the British did the same when Washington replaced London as the centre of power. Canada has this, too. We travel, and Americans don’t, we like to say; they are insular, we’re not; we elect moderates and intelligent people, they don’t; we’re not extreme in our religion, and they are. There are elements of truth in all this—as well as risible leaps of mythology.

Certainly, in some areas, an informed criticism is in order. American Christianity, for example, is dangerously nationalistic, and the Americanization of the faith has genuinely distorted its meaning. More than 80 per cent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, while the Christian right leads battles against abortion rights and LGBTQ equality, and conservative Roman Catholics have proven to be enormously influential in right-wing politics and media. That’s not necessarily a bad thing in itself, but while high-profile conservatives announce their Catholicism, high-profile liberals seem almost embarrassed to speak of their Catholic faith—creating a false impression of authentically Catholic Christianity. There is a vibrant Catholic as well as mainstream Protestant left—but as is so often the way, the loudest noise comes from the shallowest end of the pool.

In Canada, meanwhile, Christian conservatives are simply not as powerful as their siblings to the south. In numbers alone, evangelicals compose around 10 per cent of the population of Canada, whereas more than a quarter of Americans identify as evangelical. Indeed, when it comes to the power of Canada’s religious right, I once heard Ian Paisley—the late Northern Irish firebrand who, for all his bigotry, had the spark of wit—refer, in his thick Ulster accent, to Canada’s evangelicals with an “emphasis on jelly.” In other words, he considered the Canadian Christian right to be, well, rather Canadian in its meekness.

But the truth is that Canadian Christianity is more nuanced and less polarized than in the United States. One reason is that while Americans are rightly proud of their separation of church and state, Canada’s variation is less codified and formal. Ironically, this has proven to be a liberating and empowering influence on American Christianity, as though they feel obliged to try to influence and shape the state because they’re outside it.

Another reason is that almost 40 per cent of Canadians are Roman Catholic, which is both extraordinarily high and, perhaps surprisingly, trends against conservatism and uniformity. While in theory Rome doesn’t tolerate theological dissent, in reality, individual Catholics have all sorts of moral and political positions. Catholicism is often cultural rather than religious, and so while bishops may make statements about public issues—usually marriage, abortion, euthanasia, or sex education—they know that they speak for a limited number of their flock.

MORE: Is technology the key to growing Protestant churches in Canada?

So with the exception of a handful of hardline groups on the Catholic fringe, this leaves Christian conservative politics to Canada’s evangelicals—and they’ve come relatively late to the game, with their origins being far from reactionary. After all, Tommy Douglas—the first leader of the New Democratic Party—was a Baptist minister. And Canada’s social democratic tradition was strongly flavoured by non-conformist Protestants, much in the way that the British Labour Party was said to owe more to Methodism than to Marx. There are also more than 200,000 Mennonites in Canada, and their Anabaptist and pacifist origins mean that while they can be conservative on certain subjects, they also embrace a powerful social-justice theology.

Still, conservative evangelicals and Catholics in Canada do champion campaigns against equal marriage, abortion rights, assisted dying, and modern sex-ed curricula. They also advocate for publicly funded faith schools, home-schooling, and so-called parental rights, referring to the conceit that Christian parents should be able to decide what their children learn at school, especially when it comes to sex, evolution, and other religions. They’re also prominent in rejecting accepted wisdom concerning ecology, with polls revealing that the highest rate of denial of human-made climate change is among evangelicals.

The two most influential conservatives in Canada—Andrew Scheer and Jason Kenney—are both orthodox Catholics and owe much of their success to right-wing Christians and their well-funded, well-organized pressure groups. Even at a less senior level, the 2016 election of Sam Oosterhoff, the youngest MPP in Ontario’s history, owed much to the activism and voting of the Christian right; his riding of Niagara West—Glanbrook is, after all, in the buckle of the eastern Bible belt. (The west’s belt stretches across southern Alberta.)

MORE: Why Sam Oosterhoff might just be a true conservative disruptor

It’s also home to a vibrant and political Dutch community, an important element of Canada’s religious right. The Canadian army liberated a number of Dutch cities at the end of the Second World War, and with a large Dutch population already here, immigration to Canada was inevitable. Those who came to Canada in the 1940s and ‘50s were both Catholic and Protestant, of the political left as well as right, but the themes of Calvinism—which emphasizes a traditional interpretation of Scripture, and the need for the faithful to be politically engaged—were enormously strong. Many look to the inspiration of Abraham Kuyper, an early 20-century Dutch prime minister and theologian, whose approach is summarized thus: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!’ ”

More recent immigration has also affected the Christian right in Canada, as political parties work to court various religious ethnic communities. While many are Muslim, those who are Christian often come from churches that are at the less progressive end of the scale, a fact that certainly hasn’t escaped white conservative Christian leaders. I reported on three demonstrations against Ontario’s new sex-ed curriculum, and the encouragement—or was it manipulation?—of Asian and Middle Eastern Christians by a more traditional leadership was obvious.

The enigma of this is that while any religious text is open to interpretation, the central writings of Christianity—the very handbook, if you like—are the four Gospels, and they depict a Jesus who says little and often nothing about the social, moral, and sexual issues that seem to obsess conservative Protestants and Catholics. He does, however, speak and teach consistently about the evils of social injustice, and the need to reject wealth and power and embrace the marginalized and broken. The Christian right rests its case more on the prohibitions contained in the Old Testament and in the letters of St. Paul, but often with far too little acknowledgement of their context and when they were written. Paul is simply not the misogynist or homophobe that some of his modern followers like to think he is.

It’s patronizing to completely dismiss this wing of the church. But at the same time, their monomania and approach to the Bible can be frustrating; it’s a little like trying to understand a novel by only reading the semi-colons. It’s also harmful because it hurts many who are already under attack, and it also makes Christianity appear loveless—even cruel.

The real testing ground for the political power of Canada’s religious right will be the next federal election. In spite of what his critics might think, Stephen Harper was always careful to keep social conservatives at a certain distance. Scheer, however, is far more of a true believer, and while some of his advisors are recommending caution and his public comments suggest that he will keep his faith out of the House of Commons, this son of a Roman Catholic deacon is perceived as the great hope of the Christian right. His campaign in 2019 could be buoyed—or broken—by their support.

Then again, Lethbridge is not Alabama, Niagara is not Texas, and Canadian Christianity has no Franklin Graham or Mike Pence. When Canadians next go to the polls, it may well be the great litmus test of just how much influence religious conservatives have. The answer is probably less than they like to think—but more than the secular world thinks it likes.

MORE ABOUT RELIGION:

- Atheists need to understand that religion is here to stay

- If there’s a war on Christmas, it’s being led by the most zealous Christians

- Roy Moore and the hypocrisy of America’s evangelicals

- The Reformation at 500: Grappling with Martin Luther’s anti-Semitic legacy

- Why Quebec’s Bill 62 is an indefensible mess

- Jagmeet Singh’s Quebec problem

- Q&A: Reza Aslan on religion and U.S. politics

- Atheist United Church minister to start new secular community