A rough guide to the charges against Mike Duffy

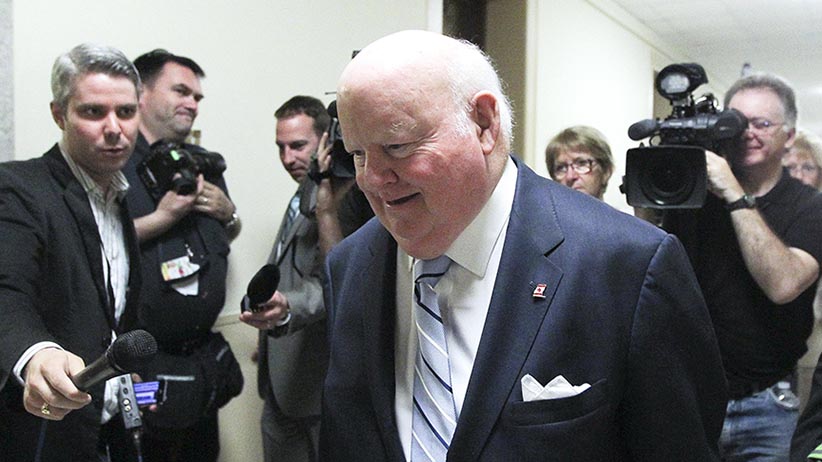

Has Mike Duffy, at one point or another in his senatorial career, committed a criminal act? Aaron Wherry takes a close look at the charges

The Senate chamber on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Thursday Jan. 13, 2011. (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

The tale of Mike Duffy, Nigel Wright and the secret cheque is the stuff of power, intrigue and politics. It is a drama that reaches within the Prime Minister’s Office and has shaken the Senate; a scandal that compelled the resignation of the Prime Minister’s top adviser and might ultimately imperil the Conservative government’s electoral chances.

The trial of Mike Duffy will revive all of this, and perhaps expose new details we weren’t supposed to know. But, for all that, the trial is still simply about one basic question: Has Mike Duffy, at one point or another in his senatorial career, committed a criminal act?

That question will be asked on 31 charges, covering four sections of the Criminal Code. (My thanks to Peter Sankoff and Michael Spratt for walking me through those charges and the relevant considerations.)

-

THE ROUGH GUIDE

Aaron Wherry’s explainer -

THE INVESTIGATION

Read the raw documents -

THE CHARGES

Read all 31 counts

The first 28 charges deal with a few different issues related to Duffy’s travel and residency claims and his dealings with Gerald Donahue, a friend of his. These 28 charges are essentially 14 pairs of charges—a charge of fraud under Criminal Code section 380(1), matched with a charge of breach of trust under section 122, the latter, because the alleged fraud was said to have been committed in the process of Duffy’s service as a public officer.

Section 380(1) states that: “Everyone who, by deceit, falsehood or other fraudulent means, whether or not it is a false pretence within the meaning of this Act, defrauds the public or any person, whether ascertained or not, of any property, money or valuable security or any service.” Charges under 380(1)(a) involve more than $5,000, while charges under 380(1)(b) involve less than $5,000.

Section 122 covers breach of trust: “Every official who, in connection with the duties of his office, commits fraud or a breach of trust is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years, whether or not the fraud or breach of trust would be an offence if it were committed in relation to a private person.”

Regarding the fraud charges, Duffy’s intent will be important. “If he was, for example, submitting expense claims and he legitimately believed that he was entitled to be reimbursed, it wouldn’t be fraud, because he wouldn’t be acting fraudulently,” says Michael Spratt, a criminal defence lawyer. “What they would need to prove is that, not only that he submitted the expense claims or took his residency money, but that he also did that, knowing that he wasn’t entitled to it to accrue a benefit for himself.”

It might matter how other senators claimed expenses and how clear the rules were. “If the standards are unclear, I would expect the defence to look for reasonable doubt here,” Spratt says. But public officials can also be held to a higher standard. Spratt points to the case of R. v. Hinchey, in which now-retired justice Claire L’Heureux-Dube, writing for the majority, said, “In my view, given the heavy trust and responsibility taken on by the holding of a public office or employ, it is appropriate that government officials are correspondingly held to codes of conduct which, for an ordinary person, would be quite severe.”

That could complicate any such defence. “The waters may need to be very muddy for this to work,” Spratt says.

On breach of trust, Spratt points to R. v. Boulanger, in which the Supreme Court set out five criteria to establish an offence: “The offence of breach of trust by a public officer is established where the Crown proves beyond a reasonable doubt that: (1) the accused is an official; (2) the accused was acting in connection with the duties of his or her office; (3) the accused breached the standard of responsibility and conduct demanded of him or her by the nature of the office; (4) the accused’s conduct represented a serious and marked departure from the standards expected of an individual in the accused’s position of public trust; and (5) the accused acted with the intention to use his or her public office for a purpose other than the public good, for example, a dishonest, partial, corrupt, or oppressive purpose.”

If Duffy is convicted of fraud, it’s likely he will be found guilty of the accompanying breach-of-trust charge.

Charges 29, 30 and 31

These three charges relate to Duffy’s acceptance of a cheque from Nigel Wright, and here is where the trial might get most complicated.

Charge 29 relates to Criminal Code section 119(1)(a), which sets out that “everyone is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years who . . . being the holder of a judicial office, or being a member of Parliament or of the legislature of a province, directly or indirectly, corruptly accepts, obtains, agrees to accept or attempts to obtain, for themselves or another person, any money, valuable consideration, office, place or employment in respect of anything done or omitted or to be done or omitted by them in their official capacity.”

More simply, this is about bribery. But that apparently raises several questions.

Peter Sankoff, a law professor at the University of Alberta, says the charge is a “stretch. This would be quite a bribery conviction,” he says. “Bribery convictions tend to be for, you bribe somebody and they did something for you. There’s a quid pro quo at the heart of the transaction.”

What did Duffy do in exchange for the money he received? And did he, wonders Sankoff, act in his “official capacity” in doing so? Was Duffy acting in his official capacity when he repaid his expense claims, or does official capacity constitute something more directly related to the powers of a senator, such as voting on, debating or studying legislation?

“It’s not a typical bribery situation,” Spratt says. “Wright isn’t necessarily gaining anything personally from it.”

Charge 30 goes at the same transaction with a different section of the Criminal Code. Section 121(1)(c) says, “Everyone commits an offence who . . . being an official or employee of the government, directly or indirectly demands, accepts or offers or agrees to accept from a person who has dealings with the government a commission, reward, advantage or benefit of any kind for themselves or another person, unless they have the consent in writing of the head of the branch of government that employs them or of which they are an official.”

Spratt says this normally involves “contractual dealings between outside entities and the government . . . Normally, this is outside contractors trying to confer benefits to get benefits for themselves.” Adds Sankoff: “This section is designed to prevent the appearance of bias in government.”

How, then, does Nigel Wright constitute a person who has dealings with the government? “Nigel Wright, unless I’ve missed something, does not have dealings with the government,” Sankoff says. “He was the government.”

Spratt notes that in R. v. Hinchey, the Supreme Court took a narrow understanding of “dealings. Therefore, I conclude that the proper interpretation of this term is the narrow one,” L’Heureux Dube wrote, “whereby only where persons are in the process of having commercial dealings with the government at the time of the offence is the conduct trapped under the section.”

Charge 31 is another charge of breach of trust, this time, in relation to the cheque. Once again, Sankoff notes, the Crown must demonstrate that what Duffy did was in connection with his duties as a senator.

Bonus question #1: Why wasn’t Nigel Wright charged?

Charges 29 and 30 could raise a question that continues to linger over this affair: Why wasn’t Nigel Wright charged? Whether or not that becomes clear as a result of Duffy’s trial, RCMP Commissioner Bob Paulson has said that question would eventually be answered. It could be that the intent—Wright has said his intention was to repay taxpayers—or the evidence did not support a charge.

Bonus question #2: What about the Parliament of Canada Act?

Section 16 of the Parliament of Canada Act dictates that “no member of the Senate shall receive or agree to receive any compensation, directly or indirectly, for services rendered or to be rendered to any person, either by the member or another person, in relation to any bill, proceeding, contract, claim, controversy, charge, accusation, arrest or other matter before the Senate or the House of Commons or a committee of either House . . .”

It also states: “Every person who gives, offers or promises to any member of the Senate any compensation for services described” is guilty of an offence.

Rob Walsh, a former law clerk of the House of Commons, has pointed to this statute as potentially applicable, and both the NDP’s Charlie Angus and Liberal MP Sean Casey have raised it in letters to the RCMP. And although the Canadian Press discovered that the director of public prosecutions had not been consulted by the RCMP—a potentially relevant fact, because the public prosecutor would have been responsible for a charge under the Parliament of Canada Act—Paulson then told the Globe that the Parliament of Canada Act had been considered.

It seems no one has ever been convicted under section of the Parliament of Canada Act, though.

APPENDIX I: THE INVESTIGATION

On June 24, 2013, RCMP Cpl. Greg Horton filed an access-to-information request to obtain a production order that detailed his allegations that Duffy had broken the law.

On Nov. 15, 2013, Horton filed an access-to-information request to obtain a production order that detailed his allegations that both Duffy and Wright had run afoul of the law.

APPENDIX II: THE CHARGES

On July 17, 2014, the RCMP charged Duffy with 31 counts. Following the charges, RCMP Assistant Commissioner Gilles Michaud made a statement:

Duffy’s charge sheet lists the details of each count.

Mike Duffy's charge sheet

Duffy’s lawyer, Donald Bayne, released a statement that responded to the charges:

“This has been a difficult year for Mike and Heather Duffy, financially, emotionally, and, for Mike, health-wise. He has had to undergo a second open-heart surgery, required serious follow-up (invasive) medical procedures at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, and he still has serious heart problems.

Nevertheless, Sen. Duffy is thankful that the awful 16 months of waiting through a protracted and highly public police investigation are finally over, and we can move on to an impartial forum and fair hearing.

To date, Sen. Duffy has never had a fair hearing, either in the Senate or in the media.

We are confident that when the full story is told, as it will be, and shown to be supported by many forms of evidence, it will be clear that Sen. Duffy is innocent of any criminal wrongdoing.

Despite Sen. Duffy’s serious ongoing health problems, which compromise his strength, and, despite his limited resources, he intends to defend fully and fairly and to show that the truth and innocence are on his side.

Those—including many in the media—who have been so eager and quick over the past year and a half to malign and even libel Sen. Duffy, without his ever having had a fair hearing, should slow down their rush to judgment and let fair process determine this matter.

I am sure that I am not the only Canadian who will now wonder openly how what was not a crime or bribe when Nigel Wright paid it on his own initiative became, however mysteriously, a crime or bribe when received by Sen. Duffy.

The evidence will show that Sen. Duffy did not want to participate in Nigel Wright’s and the PMO’s repayment scenario, which they concocted for purely political purposes.

There is much that is offensive here. But the evidence will show that it did not emanate from Sen. Duffy.”