B.C. gets a new premier. The system worked.

After weeks of waiting and wondering, B.C. watches John Horgan lead the NDP to power. And our democracy remains intact.

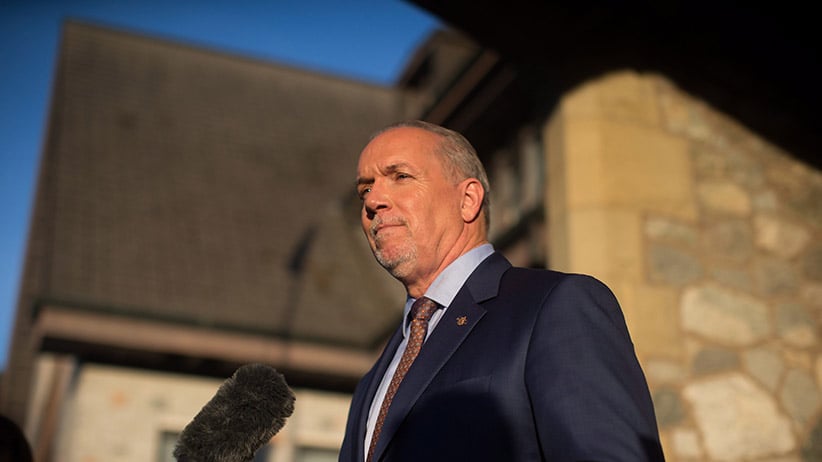

British Columbia Premier-designate, NDP Leader John Horgan pauses while speaking outside Government House after meeting with Lt-Gov. Judith Guichon in Victoria, B.C., on Thursday, June 29, 2017. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Share

What a time to be alive in British Columbia. It’s been over seven weeks since the May 9 election, and much of that time has been spent speculating about what the political landscape in the province would look like after voters returned a hung legislature. Now, after all the waiting—which, as Tom Petty will remind you, is the hardest part)—we finally have an answer: NDP leader John Horgan will be B.C.’s next premier. He will soon prepare a Throne Speech, test the confidence of the legislature, and receive it. Habemus premier!

Now, plenty of post-mortems about all of this will flood our social feeds in the days to come, with lots of picking apart of who did what, to whom, where, when, and why. Like a series of games of Clue, but for nerds. Well, for different kinds of nerds. But ultimately what we ought to keep in mind alongside the best analysis is that at the end of the day, through it all, our system worked, and it worked pretty well. Isn’t that nice?

After election day in May, no single party held a majority of the legislature’s 87 seats. After 16 years in power, two premiers, and four majority governments, the Liberals were knocked down to 43 seats, while the NDP won 41, and the Greens tripled their count to three. While the popular vote in and of itself doesn’t matter in our system, it can be telling. In 2017 in B.C., it certainly was. The Liberals won 40.36 percent while the NDP managed 40.28—effectively a tie. So, it was a close one to say the least, and it reflected a polarized province that was just asking for trouble.

After the vote, Premier Christy Clark, head of the province’s Liberal Party (which is not the same as the federal Liberal Party) remained premier and exercised her right to meet the House to test its confidence in her government, and thus determine whether or not she could remain in power. Meanwhile, John Horgan and Green Party leader Andrew Weaver struck a bargain known as a “supply and confidence agreement,” that laid out a joint policy agenda and a Green Party pledge to back the NDP on the money bills and confidence votes. The Liberals had tried to reach a similar agreement with the Greens, but failed to do so.

Forty-five days after the election, B.C.’s lieutenant governor, Judith Guichon, delivered Clark’s Speech from the Throne. The policy program offered by the premier, err, “borrowed” heavily from the NDP and Green platforms. It was all a remarkable, desperate, and cynical ploy on the part of the premier to cling to power and prepare the ground for the next election—and it failed, at least at achieving the former. Soon after, Clark held a press conference, claimed she wouldn’t advise Guichon on what to do—even though that is her job—but nonetheless worked overtime to signal that the legislature was unworkable and thus doomed.

On Thursday, members of the Legislative Assembly defeated Clark on a non-confidence motion. Clark visited the Lieutenant Governor and promptly broke her word, asking for a dissolution of the legislature and an election after promising she’d do no such thing. Guichon was having none of it. She consulted her advisors and weighed her options, and she made the right call: she quickly asked Horgan, who has a working majority in the legislature, to become premier. After all, when possible, elected officials should be given a chance to govern. And now here we are.

As this saga played out, we had a government, roads, police, schools, buses, oxygen, and even sunshine. There was no violence in the streets. Nobody fled the province. Sure, many journalists, pundits, partisans, and academics (including me) ran around wondering aloud what was next, and some commentary reached histrionic levels, but most people just went about their lives. While there was plenty of uncertainty around who would be premier in the months to come, what the Lieutenant Governor would do, and what all of that would mean for British Columbians, life found a way. The whole thing reminded me of the poet W.H. Auden and his stunning piece

Musée des Beaux Arts, in which he draws upon the myth of Icarus and the 16th century Dutch/Flemish painter Pieter Breughel the Elder:

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on

When we talk about politics it’s easy to focus on the drama and the melodrama, the scandals and nasty bits, the shortcomings and the failures. It’s so easy to be critical and pessimistic. That’s fine. To some extent, we should be vigilant when it comes to critique and we should bust our asses to keep politicians honest and accountable. But it’s also necessary from time to time to appreciate what works—especially structurally. Our ancient system, far from perfect as it may be, worked in British Columbia in 2017—as it long has. We had an election. We returned 87 MLAs. They worked out who’s going to govern the province, with some help from the Lieutenant Governor. And while they went about their business, things were generally fine. Some fuss, some muss, but not too much of either.

Admittedly, avid readers might want to push back here. A few weeks ago

I called for another election in B.C.; I stand by that call, and yet, on balance, I think the system worked. Why? Because despite some shortcomings, that system encourages us to process disagreement and struggles for power and ultimately produce a peaceful, democratic outcome that at some point, sooner or later, will revert to fairly predictable outcomes and stability. That’s a big damn deal.

Now, I’m no Pollyanna: in the months to come, the NDP government will face several serious challenges in what will almost surely be a difficult legislature to navigate. Who will be Speaker, and will they be regarded as excessively partisan? Will that person have to vote to support the government on ordinary legislation (in violation of convention)? Will the Liberals, in opposition, be so obstructionist that nothing gets done? Will the government last longer than my moribund dieffenbachia? For what it’s worth, I think the answers are: yes; yes, which is too bad; and maybe, but not much longer. And you know what? If it all falls apart in the months to come, the system will work again: we’ll have another election and voters will sort out the mess.

Again: isn’t that nice?