Life, death and politics

The death of Alan Kurdi and the federal election campaign of 2015

Share

The thing about politics is that it deals with things that matter. Not every point of popular debate is a matter of life or death—the Mineral Exploration Tax Credit could likely be maintained or repealed without profound impact to anyone’s well-being—but various other issues are or have the potential to be. Climate change or the health care provided to refugee claimants or the treatment options provided to heroin addicts or war or security or any number of social or justice policies, these are things that actually matter to the welfare of our fellow man. It might not always been conducted as such, the participants might not always approach it as if it did, but politics matters. This is something that shouldn’t ever be quite forgotten. This is what separates politics from, say, pro wrestling.

It is consequently possible that sometimes the horrible reality of human tragedy will intrude.

“This is something that goes beyond politics,” Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau said this morning.

“This,” in this case, was the death of Alan Kurdi, age 3, as captured and conveyed by the image of his body washed ashore at a Turkish beach, and thereafter the question his death became.

But this assessment of Trudeau’s wasn’t quite right. We might wish for it to be beyond cheap or crass politics—or simply beyond the usual manner of consideration—but almost nothing is beyond politics. At least insofar as politics should be understood as the process by which popular will and interest shape our society through public policy and collective effort.

“This morning we see a little boy getting picked up on a beach,” NDP Leader Tom Mulcair said from a café in Toronto, tears in his eyes, his voice wavering. “As a dad and a grandfather, it’s just unbearable that we’re doing nothing. Canada has an obligation to act and it would be too easy this morning to start assigning blame. Chris Alexander has a lot to answer for, but that’s not where we are right now. We’re worried about how we got here, how the collective international response has been so defective, how Canada has failed so completely.”

“I can’t even imagine what that father is going through right now,” Trudeau said later, his eyes welling as he stumbled for words.

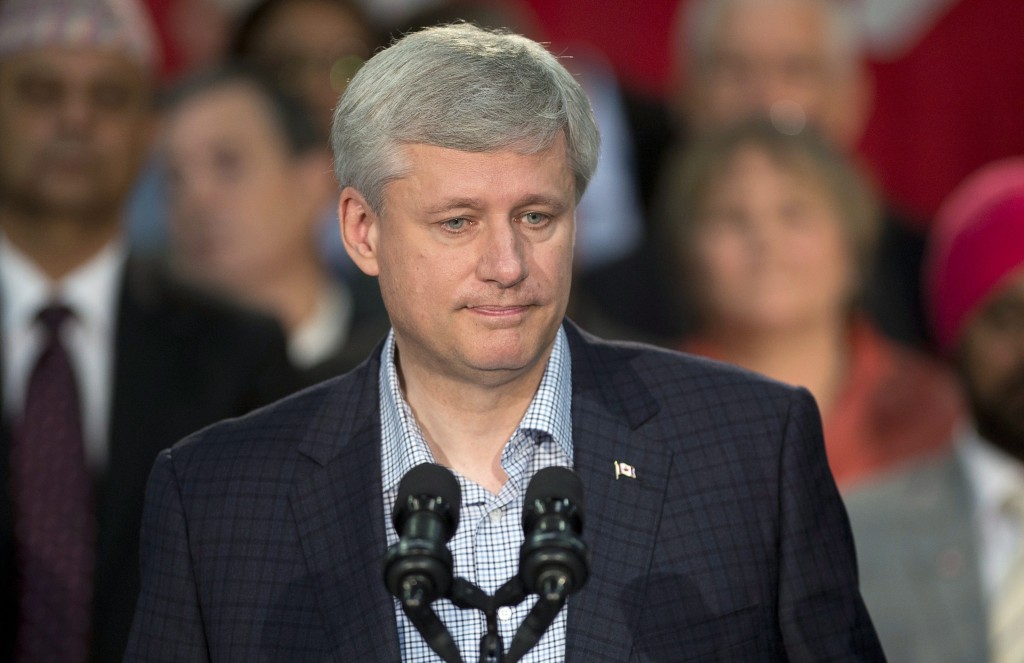

“Yesterday, Laureen and I saw on the Internet, the picture of this young boy, Alan, dead on the beach. Look, I think, our reaction to that, you know the first thing that crossed our mind was remembering our son Ben at that age, running around like that,” Stephen Harper said, becoming teary-eyed and choked.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

The precise details of Alan Kurdi’s situation are complicated. The picture was already a matter of public record yesterday. But this morning the story was that his father had applied for resettlement in Canada and been denied. And that changed how everyone understood Alan Kurdi’s death.

Chris Alexander, the Immigration minister, left his riding to confer with officials in Ottawa. Jason Kenney cancelled what was to be an “important announcement on Conservative efforts to protect the integrity of Canada’s immigration system and the security of Canada.” The Prime Minister cancelled a photo opportunity and then used a campaign event to address the situation. On Wednesday evening, this was about Chris Alexander stumbling in a TV appearance. By Thursday morning, this was about our shared humanity.

“It’s about who we are,” Trudeau said, “and what we want to continue to be.”

Contra Alexander’s attempt to blame the news media, the situation of Syrian refugees has been the stuff of headlines going back months—for some of this magazine’s coverage, see here, here and here—and the minister and his government have been pursued at various points with questions about their commitments and actions. And now they, and their political rivals, might be pursued anew. Indeed, that this occurred during an election campaign, when media and public attention is as focused as is possible, could be something of a sad blessing.

And what might’ve been—or might still be—a story about how one three-year-old boy didn’t come to be safe in Canada is now a story about how we should react to the prospect of millions of displaced people. Probably it should’ve been about that before this was anything to do with Canada explicitly. But at least it now belatedly is. Possibly now there is some desire to have this debated and explored.

“We could drive ourselves crazy with grief if we look at, as I say, the millions of people literally who are in danger, the tens of thousands who are dying. We could drive ourselves crazy with grief,” the Prime Minister said this afternoon. “Obviously we do what we can do to help.”

There is no doubt some need to be reasonable and rational about what is possible. We probably can’t, as a nation and as individuals, save every person who faces danger in this world. But exactly what we can do to help is now a legitimate point of debate. That is precisely the question.

Can this country accept more of those fleeing Syria? Can we get them here faster? How many can we take and how quickly can we get them here?

It would seem to be the government’s position that its current commitments—10,000 refugees from Syria over the next three years, plus 10,000 members of religious minorities in Syria and Iraq—are sufficient and that we mustn’t forget about fighting the Islamic State. But even if the Islamic State were made to disappear tomorrow, there would still be people fleeing Syria (and other countries). The New Democrats say they would get 10,000 Syrians here by the end of the year. The Liberals have said they’d aim for 25,000 as soon as possible. Both need now be pressed for details.

“My kids have to to be the wake-up call to the whole world,” Abdullah Kurdi said of his boys, Alan and Galip.

“I think that it’s time to wake up,” says Martin Mark of the Toronto Catholic Archdiocese’s Office for Refugees.

Mark says processing times have improved in recent years, but that other things might be done to accelerate the resettlement. He thinks Canada could double the number of refugees it accepts and aim to make Syrians half of that total—he also notes that increasing the number of Syrian refugees shouldn’t mean decreasing the number of refugees from other nations. He supports fighting ISIS. He believes both the public and the government need to do more for refugees. That history will judge us.

“We don’t say there is a world war, but definitely we can say that the world is in a state of war now,” he says. “If you see the situation in Kenya, if you go to Nigeria, if you see Cameroon, if you see Chad, if you see the Central Africa Republic, if you see how volatile the situation in Lebanon is, if you see the northern part of Jordan, if you see the different explosions in Turkey, it shows that we are at a stage of war. It’s really, really horrible.”

That is the thing about Alan Kurdi. He was not nearly the only one trying to escape. And Syria is not nearly the only place from which people want to escape.

That that should be a matter of precedence in our politics was just not understood, accepted or obvious. Perhaps now it is. It is the way of election campaigns that issues are formally seized upon, debated, fact-checked and discarded in the space of a day or two. Some matters linger all the same, around and beyond the televised proceedings. And sometimes things change.