Meet the man who helped make his friend Canada’s next PM

He’s seen as the protective knight to the prince. How Gerald Butts helped mastermind Justin Trudeau’s victory

Justin Trudeau on the road during 2015 Federal election campaign. Adam Scotti/Liberal Party of Canada

Share

On a recent sunny morning, Justin Trudeau bounded off his tour bus and into the campaign stop of the morning, a cavernous warehouse on the industrial scrapes of Montreal’s Côte-Saint-Paul neighbourhood. The next 30 minutes were a scripted variation on many of the 40 previous campaign stops: Trudeau shakes hands with business owners and the local Liberal candidate; Trudeau gamely tests whatever widget the business is selling; Trudeau stands in front of a wall of Liberal notables, delivering his campaign spiel and trashing his opposition. Then there is the second-to-last act of the spectacle: Trudeau takes questions from the media.

Gerald Butts stood behind everyone, away from both the media horde and the scads of Liberal staffers scattering about. Tall and slim, his outfit seemed to be as scripted as the campaign stop: black horn-rimmed glasses, tweed blazer over open-collared shirt, blue jeans and brown leather shoes. He fiddled with his smartphone as Trudeau, 30 m away, laced into NDP Leader Tom Mulcair, only looking up when he heard a question from a television journalist asking whether the Liberal party was lurching left to compete with the NDP.

“That’s the dumbest f–king question in Canadian politics,” Butts said to no one in particular, then turned his attention back to his phone. Minutes later, shortly after Trudeau performed the “Trudeau jaunts back onto the bus” segment of the stop, Butts slid in behind the boss. He then took to his Twitter account to talk up Trudeau’s economic plan, attack a national newspaper chain for critiquing it, and wonder out loud whether any of Trudeau’s rivals had any principles to speak of.

Related: The 2015 election’s realignment of the political spectrum

Tradition has it that the power of a senior political operative is matched only by his discretion. As principal adviser to the leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, Gerald Butts is one of perhaps five people with whom the Liberal leader consults, relies on and trusts enough to make sure he becomes prime minister. And while this makes him powerful, he isn’t particularly discreet.

Since Trudeau was elected Liberal leader in 2013, Butts has shaped and branded the vast majority of policy on which Trudeau is currently campaigning. He at once works literally inches from Trudeau and from 1,000 feet up, guiding the tectonic plates of Trudeau’s bid for the highest seat in the land. “His influence is profound on this campaign,” says consultant and pollster David Herle, who advises Liberal campaigns.

Butts is also Trudeau’s closest friend since their days together at McGill University, a fact that has informed and influenced their political relationship. Liberal observers (Butts declined interview requests for this article) see a deep bond between the pair, part blood brother, part protective knight to Trudeau’s prince.

In the early days of his leadership, when things were going swimmingly and some of those same observers were referring to Trudeau as a “stallion” and a “golden goose,” Butts was the wunderkind whose only job, it seemed, was to enable the second coming of Trudeaumania. He was the acerbic strategist behind Trudeau’s golden facade.

Things have become more complicated with the sudden, surprising rise of the NDP. Pulled to the centre by leader Tom Mulcair, the erstwhile socialist party has challenged the Liberal party as the go-to vaguely leftist party to which Canadians tend to flock when they’ve had enough of the Tories.

In many respects, the electoral fate of the party rests on the shoulders of this 44-year-old son of a coal miner from Cape Breton, who became an English literature graduate and, eventually, political Svengali. Praised even by his detractors for his policy breadth and political knack, he has nonetheless drawn the ire, however muted, of some Liberals existing beyond the echo chamber of the leader’s office.

They blame Trudeau’s entourage, Butts in particular, for the Liberal party supporting Bill C-51, the Conservative government’s far-reaching terrorism legislation that, they say, goes against the very Constitution the Liberal party birthed.

Other critics say his frequent partisan attacks on social media are a betrayal of the politico’s code of discretion, and of the supposedly positive campaign Trudeau promised he would lead. One recent example: During the Globe and Mail leaders’ debate, Butts accused a former aide to Stephen Harper of “speak[ing] dog-whistle” (speaking in racially coded language, essentially) for defending Harper’s maladroit reference to “old-stock Canadians.”

Others still blame Butts for cutting off both access to and dissension against Trudeau’s office. “The problem with Gerald is that if you are a single voice speaking to Justin, you aren’t allowed dissent. Anyone who doesn’t stick to the line that Gerry sets out has no place in the inner circle,” said one former Liberal staffer. “I quit because of Gerry Butts.”

Of course, such criticism will wither away, if Trudeau becomes the next prime minister. Having made himself the near-sole personal and political minder of Justin Trudeau, Butts has essentially laid out a bargain for himself. He will be praised to high heaven should Trudeau win. Should Trudeau lose on Oct. 19, he more than likely will be out the door before sunset the next day.

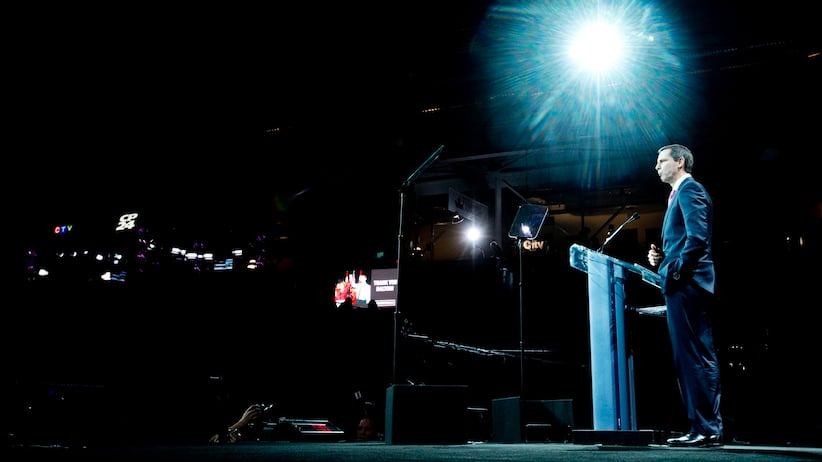

The first commercial break during the Maclean’s debate last August came at about the 25-minute mark, after a spirited exchange on the economy. Each leader was approached by his or her designated adviser for the night. Tom Mulcair chatted with Jim Rutkowski, an NDP veteran. Green Leader Elizabeth May conversed with her daughter, while Harper’s son, Ben, towered over his dad for the few minutes that the cameras were at rest.

Butts, Trudeau’s chosen adviser, approached Trudeau and practically pinned his friend against the wall. He slung a jacketed arm over Trudeau’s shoulder and spoke in hushed tones, inches from his face. It wasn’t so much aggressive as intensely friendly—a boxer with his longtime coach—with Trudeau occasionally nodding at Butts’s words. The next two breaks were similar: While Mulcair, May and Harper chatted with their advisers, Butts looked as though he might send Trudeau back in with a mouthguard.

It was a snapshot of their relationship, and an indication of how far Butts had come. He was born in 1971 to Rita and Charlie Butts of Bridgeport, N.S., the youngest of five children. His father saw dozens of fellow miners die in the coal pits of Cape Breton; his mother, a nurse, cared for many who survived. “My dad never looked for a reason to be unhappy, though he had plenty in close proximity,” Butts wrote of Charlie in 2014. “It was almost as if he didn’t see the point. It was a waste of his time and energy.”

Peggy Butts, Charlie’s sister, heavily influenced Gerald’s politics and sense of partisanship. A Catholic nun, Peggy was a schoolteacher and social activist, credentials one might think would make her a deep-orange NDPer. Yet she was a lifelong Liberal, appointed to the Canadian Senate by former prime minister Jean Chrétien.

Butts would later remember why his aunt so mistrusted the NDP, which she felt took working-class Maritimers for granted. “The only thing that’s as bad as hating someone is loving someone stupidly,” Butts said his aunt told him.

Butts first left home in 1989 to attend McGill University. In 1993, he met Justin Trudeau on the steps of the school’s student union building. In a picture of the two in those years published in Common Ground, Trudeau’s 2014 biography, a tanned Trudeau sits resplendent in acid-washed jeans and a white cutoff T-shirt next to Butts, whose long hair and backward flat cap suggest a wayward Pearl Jam roadie.

Butts, then vice-president of the McGill Debating Union and decidedly apathetic about politics and politicians, nonetheless convinced his new famous friend to join. Trudeau was also busy being Trudeau. He was a staple of the Saint Laurent Boulevard bar scene of the mid-’90s. There was dinner and drinks at Globe, dancing at Jai Bar, even the occasional impromptu twirl on the luminescent bar at Go Go Lounge. In times like these, Butts was largely in Trudeau’s shadow. It was hard to be anywhere else.

After graduation, Trudeau went off to travel the world, read War and Peace and eventually become a math and French schoolteacher.

Butts completed a master’s in literature (he loved James Joyce), then pursued a Ph.D. at York University in Toronto. His adviser, philosophy professor Howard Adelman, remembers a genial, if cocksure, student. “It’s a good old cliché, but it’s true: Gerry Butts is a bit intolerant of fools,” Adelman says. He remembers a faculty member with whom Butts frequently clashed. Butts made as much known to Adelman and others. “He had contempt for the guy, and he didn’t hide it,” Adelman says.

Disillusioned with academia and reportedly compelled by his anger at the tax-slashing reign of Ontario premier Mike Harris, Butts abandoned his pursuit of a Ph.D. for a policy gig at Pollara Strategic Insights, a Toronto-based polling firm with close ties to the Ontario Liberal party. It afforded him a front-row seat to Ontario Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty’s lacklustre 1999 campaign, in which the party squandered its early lead to lose to the Progressive Conservatives.

McGuinty was seen as wooden and patrician—a man who could barely coax a smile from his pursed lips. “And we were up against a popular incumbent [Mike Harris], a strong provincial NDP party, and Dalton had no public profile,” says Pollara chairman Michael Marzolini.

Shortly after the election, Butts sent a three-page letter to McGuinty. In it he outlined what he felt the leader had to do to win the next election. McGuinty, Butts posited, lost because he wasn’t known for anything other than being the anti-Harris guy. He suggested the would-be premier should think of three things he wanted to do as premier, then take former prime minister Lester Pearson’s lead and devote two years to planning a platform. He suggested McGuinty surround himself with the best people in the world—Butts included. McGuinty obliged, hiring the 29-year-old as his principal secretary.

How much Butts had to do with the political resurrection of Dalton McGuinty, which led to massive Liberal wins in 2003 and in 2007, remains an open question whose answer depends largely on one’s political stripe. “In 1999, we weren’t ready for the election or government,” says David Harvey, one of McGuinty’s senior advisers. “We basically started working on the 2003 platform in 1999. It was researched and costed out; it was a very focused effort.” Butts, he added, “led it all.”

Others—Conservatives, for the most part—credit Butts with little more than impeccable timing. “Butts came along at a good time, after Dalton got kicked in the balls by us and decided to buy a jock,” says a veteran Ontario Conservative war-room operative. Still, the operative grudgingly admits, “They had some strong policy ideas that originated from Butts, and they were successful.”

A Liberal government, McGuinty promised over the course of two election campaigns, would snuff out Ontario’s coal-fired electrical plants, cap classroom sizes and implement a poverty-reduction strategy, as well as save much of southern Ontario’s green space from the developer’s shovel.

Butts the policymaker helped to conjure the policies. Butts the political operative helped to sell them, along with a smiling McGuinty. “I can’t even remember a time when Dalton made a big policy decision without Gerald being involved,” says John Brodhead, one of McGuinty’s senior policy advisers at the time. “He was McGuinty’s right brain. Gerald is one of the biggest policy brains I’ve ever worked with in my political career. Some people are pure policy wonk, some people are pure communications people. He was a real hybrid.”

McGuinty’s big, expensive 2007 promise of a poverty-reduction strategy—which included the implementation of full-day kindergarten and an increase in Ontario’s minimum wage—served as both a rallying point for progressives and a wedge issue to differentiate the Liberal party from the provincial NDP, which, under leader Howard Hampton, had grown into a credible threat. “We put Hampton in a hell of a box in 2007. We outflanked him on the left,” Brodhead says.

The careful development and rollout of flashy, progressive policy, the polished delivery of it on the campaign trail, the all-important wedge issue to try to isolate the NDP: Gerald Butts’s fingerprints on the McGuinty campaigns in 2003 and 2007 are as evident on the deficit-spending Trudeau campaign of 2015. Another similarity: In the space of a few months, Butts quickly became very close with McGuinty.

“They found in each other a shared sense of values,” says Alex Johnston, McGuinty’s executive director for policy. “It wasn’t just public policy, but the way they envisioned the future. They were very sympatico. Not similar, sympatico. It was a beautiful thing to watch.” The relationship itself became fodder for a 2003 Progressive Conservative attack ad, which referred to Butts as an “unelected, backroom spin doctor.”

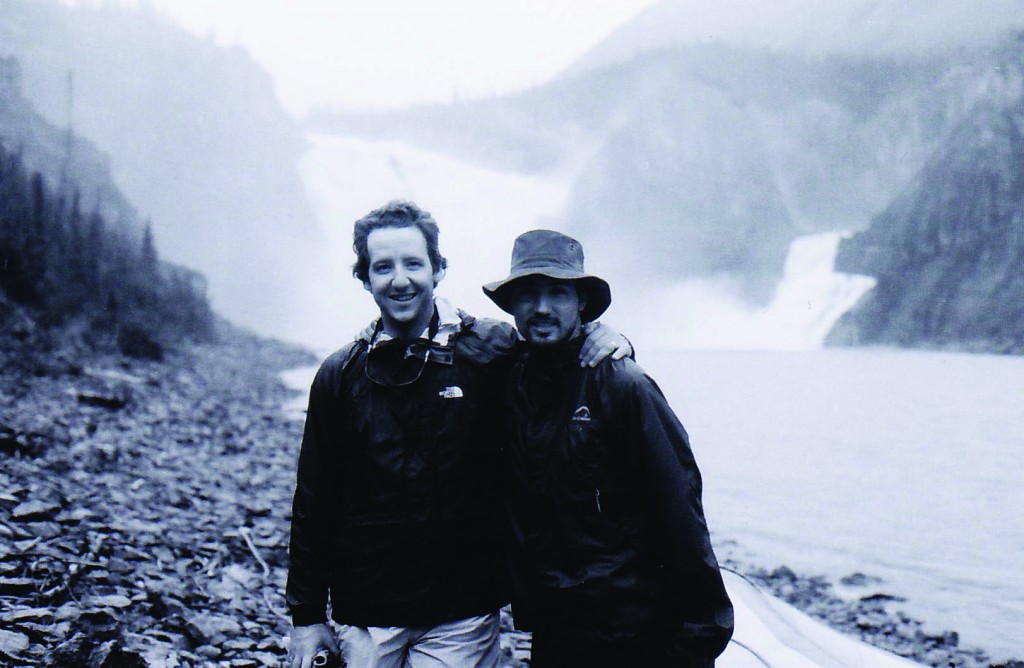

All the while, he remained close with Trudeau. In July 2003, Trudeau, Butts and a film crew went on a canoe trip on the South Nahanni River in the Northwest Territories. The pair posed at the base of Virginia Falls, the very spot where Pierre Trudeau stood while on a similar trip more than two decades before. “I had a feeling the two were going to run for the Prime Minister’s Office one day,” says Nadine Schwartz, the photographer who accompanied them.

Butts’s reputation for a salty tongue and an intolerance for fools, meanwhile, followed him from the classrooms of York University. “After 2003, Gerry became director of policy and, if one cabinet minister or another proposed things that just didn’t fit the government’s overall mission, he would just say that the guy is f–king crazy and we’re not going there,” says Greg Sorbara, who served as Ontario’s finance minister under McGuinty. “I think, often, it helped, but sometimes people got bruised and they’d say, ‘Who the f–k does Gerry Butts think he is?’ ”

In late September 2012, Butts was walking around the Princess Royal Island forest on British Columbia’s north coast, observing the native white-furred Kermode bears as the leader of a group from the World Wildlife Fund. He’d been president of WWF Canada since September 2008; after eight years, he’d left McGuinty’s office with two young kids and a case of burnout. The WWF position allowed for regular hours and a chance to pursue environmental initiatives he’d championed with McGuinty—and, on the side, to guide the burgeoning leadership aspirations of Trudeau. Butts played little role in Trudeau’s successful campaign to become MP in 2008. It would be a different story in 2012.

In the forest, Butts’s group happened upon another led by Ross McGregor, a Toronto-based capital fundraising consultant whom Butts knew. “So where do I get a button?” McGregor asked.

“The Canadians for the Great Bear button?” Butts said.

“No, the Trudeau button,” McGregor said.

Butts was surprised; though he knew of Trudeau’s planned announcement on Oct. 2—the birthday of Trudeau’s brother Michel, killed in an avalanche in 1998—news of it had apparently leaked. Butts used McGregor’s satellite phone to call Katie Telford, the director of Trudeau’s nascent campaign. “I told him that it was all hands on deck,” Telford says. Butts left WWF a few days later to manage the suddenly heightened media frenzy surrounding his best friend of 19 years.

Trudeau easily won the Liberal leadership seven months later, and Butts set to work on the policy. The broad lines of what Trudeau would eventually campaign on had been hashed out in August 2012, at a meeting of what would become Trudeau’s inner circle: Butts, Telford, Herle and Tom Pitfield, a childhood friend of Trudeau and son of former Pierre Trudeau mandarin Michael Pitfield. Others, like Liberal party national director Jeremy Broadhurst, Trudeau chief of staff Cyrus Reporter, Quebec Liberal adviser and national campaign co-chair Dan Gagnier, came in the following months. “There’s a myth out there that Gerry’s the only mind in the room, and that’s just not true,” says Pitfield, now the Liberal party’s chief digital strategist.

Still, it was largely Butts’s idea to have Trudeau focus on the plight of Canada’s middle class, which he believed has suffered under Stephen Harper. One of Butts’s key initiatives was to insert the “taxing the one per cent” into party lexicon, and to ensure that Trudeau—who, unlike Butts, was born into the one per cent—repeated the phrase, along with “giving child benefit cheques to millionaires.” Both are also staples of Butts’s Twitter feed.

“Gerry is an idealistic guy. He’s a believer that government is a source for change,” says Pitfield. “Canadians are logical human beings, and he believes that if you suggest real improvements that can change people’s lives, people will vote for you.”

Sometimes, though, seeking change has meant having to deal with Trudeau’s whimsy. On Oct. 2, 2014, two years to the day that Trudeau announced his bid for the Liberal party leadership, he delivered a keynote address at a conference for Canada 2020, a progressive think tank co-founded by Pitfield. In a sit-down interview, Trudeau was asked whether he would support a combat mission in Iraq against Islamic State. His three-minute, two-part answer was a treatise on politics, cynicism and the importance of principles, in which he referred to the looming refugee crisis and Canada’s history of accepting refugees from war-torn countries.

It might have made a decent campaign ad, except for what came next. “Why aren’t we talking more about the kind of humanitarian aid Canada must be engaged in, rather than trying to whip out our CF-18s and show them how big they are?” Trudeau said, flashing a righteous glare at the crowd.

The progressive audience tittered. “I was in the audience when he said it, and I was like, ‘That’s awesome, let’s tweet it,’ ” Pitfield says. “Gerry was at the back of the room, watching. “ ‘Uh, not awesome, guys,’ he said to me.”

Conservative minister Jason Kenney, also in the audience, tweeted his displeasure at Trudeau’s “juvenile humour” to his roughly 45,000 followers. A Conservative attack ad was ready within hours. The comment, coupled with the Liberal caucus decision not to support Canada’s participation in the American-led mission against Islamic State, hurt Liberal credibility in the area of foreign affairs, says former Liberal justice minister Irwin Cotler. “When the party voted against the multilateral mission, Harper was playing the adult in the room regarding fighting terrorism,” Cotler says.

The worst for Cotler and like-minded Liberals was yet to come. Four months after Trudeau’s gaffe, the Liberal caucus supported Bill C-51, the Conservative government’s anti-terrorism legislation that gives enhanced powers to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and increases information-sharing between security agencies. Though the decision to support C-51 wasn’t only his, Butts nonetheless became the target among certain Liberals, who suggested he had influenced Trudeau’s support of the bill. As Trudeau’s numbers began to dip, in part because of C-51, the whisper campaign against his adviser began in earnest.

Sitting in his riding office in Montreal, Cotler says he didn’t like C-51, despite ultimately voting for it. The Liberals, he says, supported C-51 largely out of political considerations. “The party voted against the multilateral mission [against ISIS]. Then comes C-51. Harper’s saying, ‘I’m the guy who’s standing up to terror.’ If, after the ISIS vote, the Libs had been against C-51, then Harper would have said, ‘You can’t really trust these Liberals; they’re soft on terror, soft on crime,’ ” Cotler says. Trudeau, Cotler says, was sure the Conservatives would be open to compromise on the bill. To no one else’s surprise, they weren’t. “Justin is a decent guy. He’s not yet realized how these guys operate, maybe,” Cotler says.

For Butts, the keeper of the Trudeau narrative, it was a serious hitch. An open letter signed by three former Liberal prime ministers decried the bill’s “lack of robust and integrated accountability regime for Canada’s national security agencies,” which caused “serious problems for public safety and human rights.” Much of the Liberal rank and file, meanwhile, was just as outraged. In a series of emails obtained by Maclean’s, Montreal Liberals (including Liberal candidate David Lametti) deplored the party’s position. One lifelong partisan vowed to vote for the Green party out of protest. In May, the party dispatched Liberal MP Marc Garneau to attempt to staunch the bleeding.

It wasn’t enough. In July, Liberal MP Scott Brison hosted an $800-a-plate fundraiser at a Bay Street law firm in downtown Toronto. Roughly 20 people were in attendance, many of whom were members of the party’s Laurier Club, the party’s gilded circle of big donors.

According to an attendee, these spendy Liberals were outraged at the party’s support of Bill C-51 and its potential political fallout among voters. At one point, Brison, who readily supports the party’s position, became agitated. According to the attendee, Brison said opposition to the law wasn’t registering with Liberals or voters beyond certain “urban elites and Volvo vigilantes.” (Brison, who has used the term “Volvo vigilantes” in Parliament, didn’t remember using it that night. “I’ve owned three Volvos myself,” he told Maclean’s by way of either explanation or justification.)

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

Coincidentally or not, Liberal polling fortunes, already on the wane, fell further in the wake of the party’s position on Harper’s anti-terrorism legislation. In early August, rumour of an attempted coup against Butts quickly spread. According to the rumour, pollster and consultant David Herle was to replace Butts and Telford, until Trudeau himself intervened on his friends’ behalf.

Though quickly discredited—“utter bulls–t,” is how Herle characterizes it—the extent to which people were prepared to believe it was indicative of how Trudeau’s success or failure seems to rest on Butts. “This is a common phenomenon when a party isn’t doing as well as the membership would like, and that would be the case with us right now,” Herle says. “First, they blamed C-51. Then they blamed staff.”

Yet Herle is inclined to side with Brison. Bill C-51 wasn’t the electoral millstone some of its members might have thought. Rather, Herle believes the provincial NDP win in Alberta after more than 43 years of Tory reign over Canada’s oil patch gave its federal cousin instant credibility across the country. “For those people desperate to get rid of Harper, all of a sudden, there was this belief that if the NDP can beat the Conservatives in Alberta, they can beat them everywhere. There’s no question that there was a big jump in NDP support across the country after the Alberta election, and it has largely been sustained,” Herle says.

In congratulating Alberta’s NDP, Butts nonetheless spun the election results for his 12,000 followers. “[B]iggest lessons are old ones: long-in-the-tooth, out-of-touch governments get smoked, and leaders matter.” It was yet another of Butts’s social media jabs at Harper, but his sights were already set elsewhere, against the emerging threat of the federal NDP and its leader, suddenly jolly Tom Mulcair.

On Aug. 1, just as Canadian media and political circles were alive with rumours of his demise, Butts tweeted an attack on John Wright, a vice-president of the Ipsos Reid polling firm. Wright’s apparent sin was to have critiqued a Trudeau campaign ad. “Premier Hudak (or is it Premier Tory?) on line 2,” Butts wrote in response, referring to former Ontario Progressive Conservative leaders Tim Hudak and John Tory.

An apparent dig at the accuracy of Ipsos Reid’s polling, it was a wholeheartedly bitchy line, and Wright responded eight minutes later. “Regardless of any outcome, I’ll have a job and you’ll likely be out of yours. Sorry I get under your skin. It shows,” Wright tweeted.

Liberal operative (and Telford’s husband) Rob Silver immediately joined in. “What a jackass thing to say to anyone,” he tweeted at Wright. Another Liberal said Wright was “exactly what is wrong with this country.” Several people made fun of Butts’s family name. Journalists commented on and retweeted the exchange. The whole thing was over in about 10 minutes, and probably forgotten in 12.

Since even before Trudeau became Liberal leader, Butts’s most visible role has been to start and/or participate in these sorts of nasty, ephemeral battles on Twitter, and he does so almost daily with apparent glee. On Aug. 25, he reproached the NDP for running a negative campaign. A few weeks later, without apparent irony, he berated a conservative with all of 15 followers for misspelling the word “effete” when referring to Trudeau.

During one week last August, he averaged more than 30 tweets and retweets a day—including the weekend. He is both Trudeau’s top adviser and the loudest Liberal in the catty online mini-world of Canadian politics. His Twitter feed is a marked departure from the otherwise sunny and positive nature of the Trudeau campaign, and some see Butts’s Twitter persona as a true reflection of his personality.

“This is the way he’s always been,” says National Post political columnist John Ivison, who has known Butts for 12 years and been a target of his online ire for nearly as long. “The definition of a political adviser is to have the tenacity of a water buffalo and a passion for anonymity. I’m not sure he’s adhering to that at all. That said, I like and admire him. He’s truly one of the three smartest people I’ve met in politics.”

Behind the scenes, Butts oversees just about everything else, including the Liberals’ campaign war room. Under his direction, the focus has sharpened on Mulcair with the latter’s rise in the polls. The party recently produced a 12-page background report on Mulcair outlining possible lines of attack on him. They included everything from Mulcair’s penchant for saying in French what he won’t say in English and vice versa, to his past refusals to give up his French passport and the 11 mortgages he has had on his home.

As with the McGuinty campaign eight years ago, Butts and his team spent several months planning the all-important wedge issue to isolate the NDP. On Aug. 27, Trudeau pounced, announcing $125 billion in infrastructure spending—“the largest infrastructure investment in Canadian history,” as the Liberal campaign put it. Of course, spending oodles of money on bridges, roads and the like is nothing new, particularly during a campaign. The main difference is that the party plans on going into deficit to fund it, a marked difference from the NDP and the Conservatives.

Butts the policy wonk, along with MP Chrystia Freeland, economists Mike Moffatt and Kevin Milligan, Liberal adviser Michael McNair and former cabinet ministers John McCallum and Ralph Goodale, crafted the infrastructure strategy. (Moffatt and Milligan are Maclean’s contributors.) Butts the political salesman co-wrote the hard sell with Trudeau and, according to Liberal sources, timed the pitch to coincide with the beginning of the school year, when more commuters would likely take note of the terrible roads under their wheels.

Butts was particularly prolific on Twitter that day; he tweeted or retweeted 56 times, either attacking the Conservatives, the NDP or further burnishing Trudeau’s image. “It’s taken a lot of discipline to sit there and take a beating,” Pitfield said of attacks against Butts from within and beyond the party. “He’s a very calm customer. He has a plan, and we’re sticking to it.”

Butts’s allies, and there are many in the upper echelons of the current incarnation of the Liberal party, are his fierce defenders. He’s like his Twitter profile: Yes, he is hated—“The guy’s unpleasant. He’s not good with people,” says the former Liberal staffer—but loved in greater measure by those around him, especially Trudeau. Whether that love will translate to power is the grand gamble of Gerald Butts, to be settled in less than a month.