Federal politics 2014: The year in 12 chapters

Foreign missions to family taxes, court battles to pot politics

Share

By how many percentage points, according to the one recent poll, does Justin Trudeau’s personal approval rating top Stephen Harper’s? As part of Trudeau’s ongoing efforts to maintain that advantage, how many outside experts has he appointed to his Economic Council of Advisors? By how many years is the wily Conservative Prime Minister older than his dewy Liberal rival?

The answer to all these questions is a dozen, although, in the case of the age difference, only if we round by a few months (at start of 2015, Trudeau is 43 and Harper 55, but the PM will turn 56 in the spring). The duodecimal fixation of this article, however, is really only on the 12 months of the Julian calendar. And Julius Caesar, superior political player that he was, would surely approve of our using his invention to imperiously enforce order on our recollections of 2014, by choosing just one story a month to tell the year’s tale in federal politics.

January: We wondered if banishing senators was bold or reckless

Canada’s Senate has been a scandal pretty much since Confederation: ever packed with patronage appointees, never accountable to any voter. Trudeau opened 2014 by kicking 32 Liberal senators out of his parliamentary caucus, forcing them to organize themselves separately from his MPs. This at least had the merit of setting him apart. A few months later, Harper’s alternative—unilaterally imposing term limits on senators, as well as a sort of Senate elections—would be ruled constitutionally invalid by the Supreme Court of Canada. For his part, NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair called for Senate abolition, constitutional reform that would require improbable buy-in from the provinces. Trudeau’s gambit may have held our attention only briefly, but it wasn’t a dead end. And he promises a non-partisan appointment process if he’s ever prime minister.

February: We heard a dissenting—and too soon to fall silent—cabinet voice

Among Harper’s big promises in the 2011 election was a pledge to let Canadian couples with kids split their income, for tax purposes, as soon as the federal books were balanced. But then Jim Flaherty, the only finance minister Harper had ever had, voiced serious reservations. “It benefits some parts of the Canadian population a lot,” he said. “And other parts… virtually not at all.” Flaherty died only two months later, a loss deeply felt across party lines in Ottawa. But his last key policy intervention lived on. In the fall, Harper would announce a dramatically modified version of income-splitting, capped to limit the windfall for rich couples, and combined with other benefits for those earning less. It was a reminder of the need for strong counterbalancing figures, as Flaherty had been, in our PM-centric federal power structure.

March: We learned again how trips abroad can boost a prime minister

Harper spent much of 2014 talking tough about Russia’s stance toward Ukraine. On March 22, he made a point of being the first world leader to visit Kiev after the toppling, the previous month, of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s pro-Russian president, whose ouster annoyed Moscow. Harper’s highly symbolic, supportive visit set a tone. Later in the year, after he shook Vladimir Putin’s hand at a G20 summit Australia, the PM’s press spokesman quickly made a point of telling reporters that Harper told the Russian president: “You need to get out of Ukraine.” It was good politics back home. After losing ground in ‘13 over messy domestic issues, Harper regained his footing in ‘14 largely by going on the offensive, especially rhetorically, on foreign affairs.

April: We saw our highest court block Harper, but maybe not surprise him

The unanimous decision from the Supreme Court of Canada—a sweeping rebuke to Harper’s Senate reform plan—seemed to be a big setback for the Prime Minister. Yet few, if any, constitutional experts were surprised the court denied him clearance to unilaterally impose term limits on senators and implement so-called “consultative” elections for senators. As predicted, the judges said he needed to get the provinces to agree. But did Harper ever really expect a judicial green light? A more plausible theory is that he merely wanted to appear to have pursued Senate reform to satisfy his party’s old (Reform-rooted) hunger for a more accountable upper chamber. Still, the decision added to the frustration many Conservatives feel toward the top court, helping pave the way for the following month’s dominant story.

May: We gasped at an open political assault on the country’s top judge

Even in Stephen Harper’s hyper-partisan Ottawa, the Supreme Court of Canada had always been treated with deference—until May 1, 2014. On that evening, Harper’s press office issued a statement saying the Prime Minister had deemed it “inadvisable and inappropriate” to take a certain call from Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin. Months earlier, it turned out, she had tried to warn Harper against nominating a federal court judge, Marc Nadon, to fill a Quebec vacancy on her court. (Indeed, Nadon was later ruled ineligible, since he failed to meet the requirement that he be a Quebec judge or practising lawyer.) The public rift between Harper and McLachlin was unprecedented. The lesson seemed to be that for Harper, and his hard-hitting political staff, no target is sacrosanct.

June: We thought twice about a prostitution law’s chances of survival

No sooner had May’s war of words between Harper and McLachlin quieted down than Justice Minister Peter MacKay tabled a new anti-prostitution act, meant to replace the law the struck down by the Supreme Court in late 2013. Rather than allowing safer ways to sell sex, as the court seemed to have suggested, McKay made it illegal to buy it anywhere, anytime. The initial reaction was incredulous: Surely this tough law would, in due course, be struck down, too. Then law profs took a closer look. The bill came with a preamble, declaring its aim of stopping “the exploitation that is inherent in prostitution” and protecting the “human dignity and the equality of all Canadians.” No similar language had been attached to the old laws. Perhaps the new legislation’s lofty aims might save it in the coming constitutional challenge.

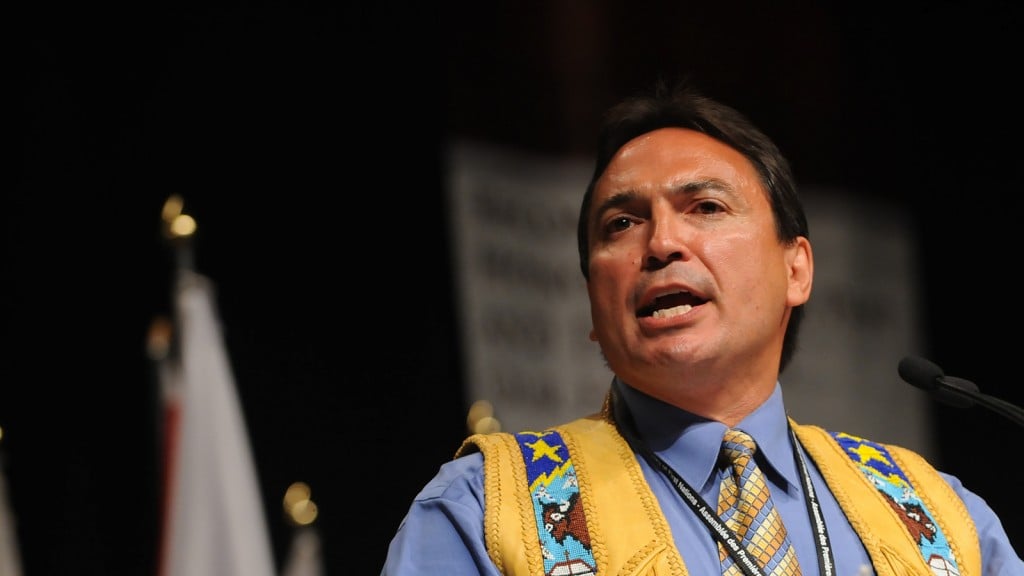

July: We took note as fractious First Nations leaders strove to regroup

In a tumultuous year for Aboriginal politics, the Assembly of First Nations’ mid-July annual meeting in Halifax was a rare moment of seeming calm. The stage for the AFN’s summer confab had been set by the surprise spring exit of Shawn Atleo, the group’s embattled national chief. Atleo had negotiated an on-reserve education reform deal with Harper, sparking angry protests from rival chiefs, which finally drove him out. At the Halifax meeting, the AFN voted to elect his successor at a December convention in Winnipeg. The winner would be Perry Bellegarde, a veteran Saskatchewan chief. Was Halifax the pivot, then, from a period defined by the AFN’s intramural squabbles, to a less fractious new stage? Or was it only a breather between Atleo’s struggle and an inevitable next round of unproductive infighting?

August: We felt for docs caught up in the politics of anti-pot ads

The Harper government asked the mainstream groups representing Canadian doctors—the College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Medical Association and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada—to lend their imprimaturs to federal ads warning young people about the dangers of marijuana. In fact, many physicians rightly worry about the effects of grass on growing brains. But the history of the Conservatives on anti-drug ads is fraught. Previous campaigns have seemed more directed at reminding voting parents about the Tories’ anti-drug stance than having a practical impact on their kids’ health. As well, the timing of the new ads seemed to dovetail suspiciously with Harper’s hard-hitting assaults on Trudeau’s legalized-and-regulate proposal on pot. So the docs didn’t sign on. And the ads proved dubious.

September: We suspected a limited military mission might lead to more

Almost from the moment Harper announced he was sending several dozen Canadian Forces special operations troops to northern Iraq, to help train Kurdish soldiers fight ISIS terrorists, his government’s open-ended way of talking about the commitment suggested that this wouldn’t be the end of it. “We could never undertake any mission if we were worried about mission creep,” said Foreign Minister John Baird. Indeed, the following month Harper would send CF-18s to bomb Islamic State targets; both Mulcair and Trudeau would oppose the airstrikes. At the end of 2014, the real effect of the roles Canada had taken on in the chaotic Middle East was hard to measure. But the consensus view among pundits and pollsters was that Harper’s image had benefited from his resolute anti-terrorist talk.

October: We got a sneak preview of the PM’s Campaign ’15 mode

The most startling news of the month was a gunman’s Oct. 22 attack on Parliament Hill. But the reaction of Canadians, even Canadian politicians, transcended politics. We were soon enough back in a more familiar political groove. In Vaughan, Ont., just north of Toronto, Harper unveiled a shrewdly modified family tax cut package on Oct. 30, on a stage populated by appreciative, smiling families. The policy itself remains highly debatable—but nowhere near as blatantly skewed in favour of well-off, one-income households as the previous version (see above: February entry). And this was only one of several fairly slick campaign-style Harper outings on economic themes, held in the rich vein of hotly contested ridings in or near Toronto. Guess where the fall ’15 election will be won or lost, and on what sorts of issues?

November: We marveled at how shrinking surpluses serve the Tories

Finance Minister Joe Oliver didn’t exactly venture into the lion’s den to offer up his fall fiscal update; the former investment banker delivered it in familiar, friendly environs of the Canadian Club of Toronto. But his didn’t come bearing any obviously upbeat fiscal message. For 2015-16, Oliver said the federal surplus would be just $1.9 billion, way down from the $6.4 billion projected last February. What happened? Well, all those tax cuts Harper had cheerfully announced, plus billions more in infrastructure spending. In other words, the cupboard was perilously close to being bare—with a federal election on the calendar for fall ’15. Not much room left for any Liberal or NDP promises, unless, of course, they want to tell voters they’d yank reverse measures already announced or even implemented by Harper.

December: We puzzled over the regional politics of falling oil prices

Here at Maclean’s, we’ve long seen Harper’s Ottawa as an oil town. Surely, then, the recent precipitous plunge in the price of crude is very bad news for Conservatives? Actually, a scan of the regional impacts leads to the opposite conclusion. Growth in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador will take a hit. But Tory seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan aren’t in jeopardy, and few ridings are in play in Newfoundland. But in Ontario, the main ‘15 electoral battleground, to falling C$ resulting from cheaper oil is a boon to manufacturing exporters. CIBC has Ontario “poised to lead the country in real GDP growth in 2015.” A bump in export-driven job-creation might well make Ontario voters start feeling better about the state of the economy, and thus less automatically inclined, by next fall’s campaign season, for a change.

(As a service to those of you so enslaved to political news that, even in this festive season, you feel inclined to compare and contrast 2014 to other recent years in federal politics, here are links to my previous 12-chapter reviews for 2013, 2012, 2011 and 2010. But, really, get back to your families.)