Our Duffy, ourselves

What a picture of Stephen Harper and Mike Duffy can tell us about politics in the early 21st century

Suspended Senator Mike Duffy leaves the Ontario Court of Justice, in Ottawa, Canada, April 8, 2015. Duffy, a former ally of Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, is on trial for fraud and bribery in a high-profile case that could hurt the ruling Conservatives’ chances of winning an election this October. Blair Gable/Reuters

Share

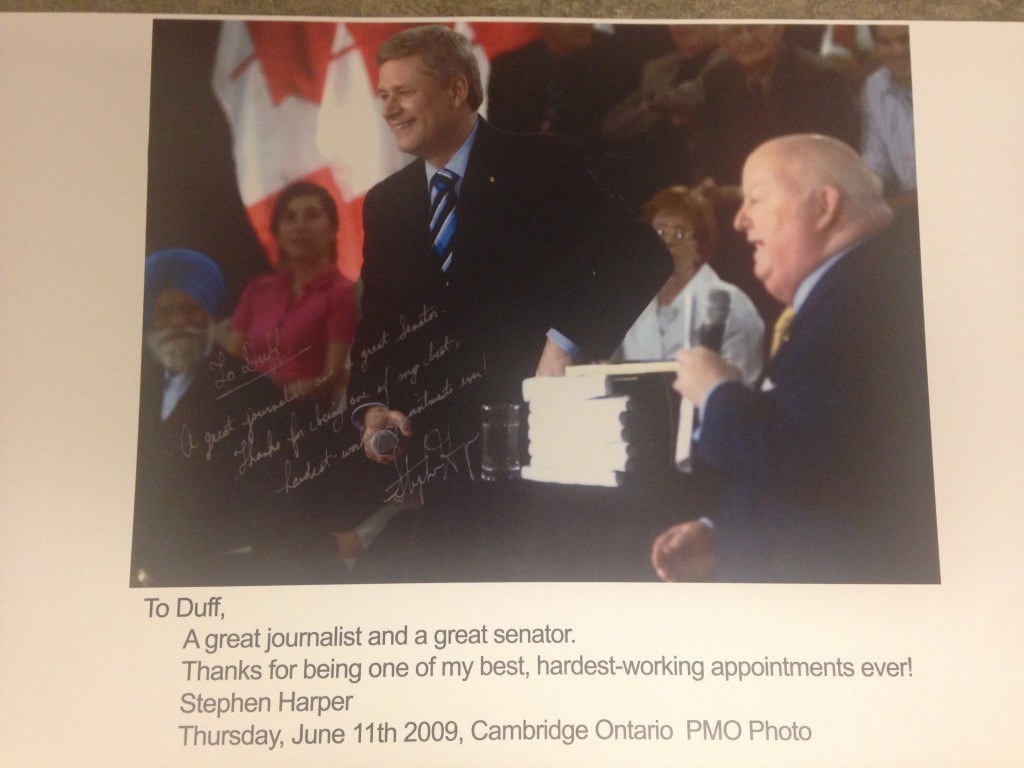

The picture is, in its own way, perfect. And not just for the inscription. It is of a moment, of this moment. A book could be written about it. But for now, let’s give it the thousand words it deserves.

Exhibit D, as it was officially registered with the Ottawa court by Mike Duffy’s lawyer last week, shows the senator and Prime Minister Stephen Harper together, on stage, at an event in June 2009. Duffy had been appointed six months earlier, one of 18 senators suddenly nominated before Christmas 2008—at a moment when Harper, as a result of the Governor General’s decision to grant a prorogation, was only barely clinging to power (having incited a Liberal-NDP coalition when he used a moment of economic crisis to propose reducing the financial resources of political parties, a move that would have wounded his rivals far more than his own party).

Duffy and his fellow appointees had apparently all pledged to support the government’s Senate reforms, pledges that now seem adorably quaint, like coming upon a picture of the games children used to play in the Victorian period.

What the Prime Minister came back with in January 2009 was what he and Duffy were advertising that day in June: Canada’s Economic Action Plan™. This was the snappy moniker given to what was actually just an earlier-than-usual budget with measures designed to stimulate a faltering economy and get the country through a global recession with minimal discomfort. And this was the title of what would become a massive marketing campaign, with billboards and television ads; a monument of self-promotion and aggrandizement, all of it paid for with public funds. In time, each federal budget would come to be styled as an Economic Action Plan—the public mind apparently too distracted or leaden to be impressed by something like a mere accounting of government spending.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Mike Duffy”]

The Prime Minister and his senator are on stage for the second report on the progress of Canada’s Economic Action Plan. These progress reports had been forced on the government by Michael Ignatieff in his pledge to put the Conservatives on “probation”—the price of winning the support of a Liberal leader who didn’t want to try his luck with a coalition government anyway. But what the Liberals wanted to portray as a demand for accountability, and perhaps imagined as future opportunities to topple the Conservatives, the government turned into quarterly celebrations of their good deeds. Ignatieff never got closer to being prime minister than he had been in January 2009 and the Conservatives won a majority in 2011.

Funny thing: while the government carefully tracked the total number and locations of its Economic Action Plan signs, in some cases with GPS co-ordinates, the government didn’t track how many jobs were actually created by its stimulus spending, so beyond signage we can only guess at what the Economic Action Plan actually amounted to. Behold the state of public policy.

The House of Commons was sitting on June 11, 2009, but the Prime Minister was in Cambridge, Ont., standing before an audience of invited guests, with Mike Duffy acting as host of the town-hall-styled television event.

“Mr. Speaker, holding some kind of weird Mike Duffy live show instead of reporting to the House will not change the facts,” Jack Layton lamented in the House, the late NDP leader begging to differ with the government’s version. “The Prime Minister is holding some kind of gong show outside of the House of Commons instead of being here to answer questions.”

To call it a gong show is likely to insult its careful staging. (Footage of anything other than Harper’s speech seems not to be readily available, so I’m reliant on contemporaneous accounts.) The Prime Minister took no questions from reporters, instead taking apparently chosen questions from his selected audience—not quite the all-comers forum we might imagine our prime ministers daring to subject themselves to. The show cost $108,000 to produce. According to Duffy’s diary, the Prime Minister’s Office paid for his hotel room the night before.

Duffy was back from Cambridge in time to appear at an event for the Ottawa South Conservative Association on the night of June 11. The next night he was in Belleville, Ont., for a fundraiser with Conservative MP Daryl Kramp—$100 per person for an evening of prime rib and the old Duff.

This is presumably the sort of thing the Prime Minister had in mind when he put in writing that Mike Duffy was one of his “best” and “hardest-working” appointments. It would not obviously seem to be praise for the scrupulous study of legislation or a tireless devotion to holding the government to account, the sorts of things that we, at the risk of being laughed at, might say a senator and an MP exists primarily to do. Rather, Duffy was a prodigious fundraiser for and promoter of the Conservative party’s cause. He was, most of all, a man for his party.

And now we have our own trial of the century and Mike Duffy standing as the most injurious controversy the Harper government has ever been dealt. The Prime Minister’s chief of staff caught cutting a secret cheque for a sitting senator. The Prime Minister’s Office caught dabbling in the affairs of a Senate committee. The Senate’s existence in question, question period briefly revived. And an opening made for Justin Trudeau or Tom Mulcair to make new history. It’s all so damn poetic. A government that has its roots in the Reform insurgency brought to the brink by a deal between a member of the Bay Street elite and a former member of the Ottawa media elite.

Exhibit D would seem to be of limited evidentiary value. But it was paraded before the cameras and was the stuff of headlines last week. It is now, of course, something of a political embarrassment for Harper. And surely there is an election ad for the Liberals or New Democrats in it.

It is not just good for a laugh, though. It is an artifact worth framing and hanging in the museum of Canadian history that this government created. You could build a whole exhibit around it—with a map of every Economic Action Plan sign, a guide to staging your very own town-hall-style television event, and a ball pit, symbolizing the Senate, for the kids. What was federal politics like in Canada in the early 21st century? It was like this. Here is what a single photo can tell us about how politics was practised, marketed, controlled, manipulated, mocked, made, undone and litigated.