Will money and arrogance cost Christy Clark the BC election?

With days left in the campaign, the stench of suspect lobbying and fundraising around her party is as bad as ever. But don’t count out Clark just yet.

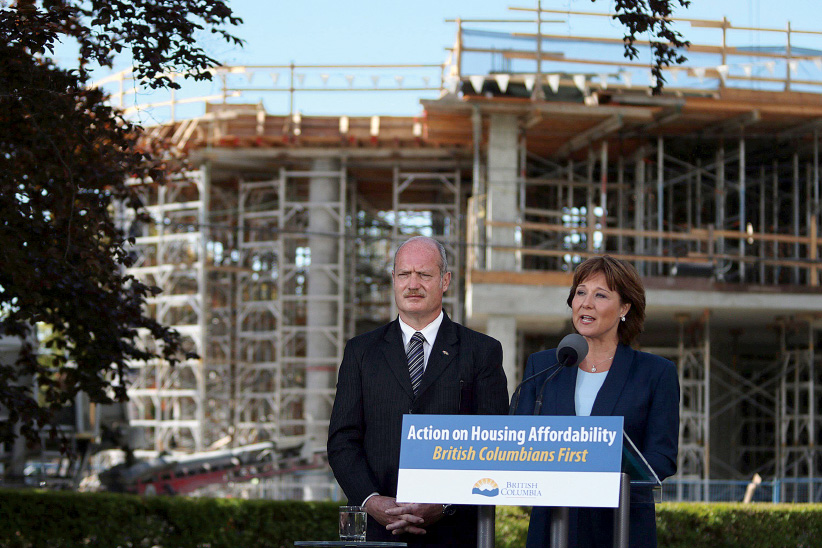

Liberal Leader Christy Clark speaks to candidates and supporters at the Elk Lake boathouse in Saanich, B.C., on Tuesday, April 11, 2017. (Chad Hipolito/CP)

Share

The encounter lasted just seven seconds, but the fallout from a voter’s chance handshake with Premier Christy Clark is haunting the governing B.C. Liberals as they enter the stretch ahead of the May 9 vote. Clark, a gifted retail politician known to shine on the stump, was in North Vancouver last weekend, when Linda Higgins stuck out her hand.

“I would never vote for you because of what…” Higgins began.“You don’t have to—that’s why we live in a democracy,” Clark snapped, turning her heels on the retired civil servant, who was left to stare at the back of her premier’s fire-red blazer, as cameras rolled.

The brush-off would certainly have faded from memory, but the Liberals’ bloated campaign team attacked on Twitter. Campaign director Laura Miller and digital strategist Mark Marissen labelled Higgins an NDP plant, hell-bent on disrupting the Liberal campaign. Their supporters jumped in, seemingly on cue, some calling Higgins a “bitch” and more.

When reporters who’d interviewed Higgins tried to intervene on her behalf—there was no evidence she’d been planted there by the NDP, and Higgins was being hounded and discredited for expressing her opinion—they were smeared as biased. But by then, the dust up was trending. Regular British Columbians were using the hashtag #IamLinda to express frustration with the governing party. The effect was to show Clark at her worst, aloof and out of touch, while revealing one of most puzzling aspects about B.C.’s 2017 campaign: how did the plainspoken, single mom raised by a gym teacher in suburban Burnaby get so tone deaf?

READ MORE: The B.C. election and the folly of strategic voting

With just days to go before the vote, the premier still appears blind to the thing most likely to break her party’s 16-year grip on power: the growing perception that a cabal of powerful people—B.C. Liberal donors, lobbyists and corporate heads—are running the province in their own interest. It casts Clark as a kind of reverse Robin Hood, “robbing the poor to feed the rich,” says Kai Nagata of the Dogwood Initiative, a nonpartisan citizen action network. “Your Hydro rates are going up, your rent’s gone up, you’re paying more in bridge tolls. Everything about your life is becoming more expensive. And it’s all done to benefit wealthy Liberal donors—the people getting tax cuts and free hydro to power their LNG projects.”

The Liberals have done little to counter the image. A week before the writ dropped, Clark announced that the chair of BC Hydro—whom the premier herself appoints—would spend the entire 28-day election campaign with her on the Liberal bus. Brad Bennett is reprising the key role he played in 2013 as Clark’s advisor and sounding board; although back then the Kelowna businessman, who refused to be interviewed by Maclean’s on the subject, wasn’t heading B.C.’s biggest Crown Corporation. Until recently, he told reporters he was refusing to take a leave of absence from BC Hydro to do it.

“Why not?” he said last month, when asked whether it was appropriate for him to side with a particular party. “We all have our right, and I would argue, our obligation, to ensure we have a thriving democracy.” (A B.C. Liberal spokesperson says Bennett did ultimately decide to take a leave, effective 11:59 p.m. April 10—the day before the writ dropped. BC Hydro says its board met on April 10 to approve it, but added the minutes from the meeting have “not yet been approved,” for release, “as they are typically approved at a following meeting of the Board”.)

Moreover, with the RCMP investigating Liberal fundraising irregularities, you might think the party would jump to bring the province’s retrograde campaign finance laws into line with those in the rest of the country—something critics and many voters have demanded for years. Clark has said only that a future panel will be convened to explore ideas surrounding campaign finance reform.

The Liberals may have good reason to take their time digging into party financing, given the intricate web linking their fundraising activities to lobbyists with well-documented ties to the party. But as a matter of political self-preservation, one is left to wonder how a leader known for her populist touch could morph so quickly into a symbol of power and privilege. Surely someone with her background would be alive to the risks of appearing arrogant and out of touch. Yet even as the campaign loomed, Clark seemed oblivious, brushing off accusations of cronyism, concerns about “pay-to-play” fundraising and—perhaps most important—repeated pleas from B.C.’s former lobbying watchdog to clean up the province’s ballooning lobbying industry.

READ MORE: Welcome to British Columbia, where you ‘pay to play’

RIGHT NOW, THERE’S nothing stopping lobbyists from serving as paid party campaign staff or war room strategists, then turning around and lobbying the premier or other MLAs, who arguably owe their jobs to them. Nor is there anything barring lobbyists from targeting the political staff, MLAs and ministers with whom they ski, cottage and party. These are just a couple of the rules in place at the federal level that govern the behaviour of those lobbying the feds; they’re there to prevent any perceived or real conflicts of interest from tainting the process. But in B.C., “there is no daylight” between top lobbyists and and the premier’s office, one lobbyist based outside the province told Maclean’s, speaking anonymously, citing concerns of professional retribution. “That line has been completely erased.”

High-profile lobbyists like Patrick Kinsella, who has donated $235,000 to the party—more than major national firms like Fleishman Hillard and Hill and Knowlton—and Steve Kukucha are also key members of the Clark campaign team. Kinsella is working in key battleground ridings in Surrey, while Kukucha, co-founder of Wazuku Advisory Group, is back as the Liberals so-called “wagon master,” managing the campaign bus and media plane. Wazuku, in the last election also worked on the campaign for one of the so-called “dark money” groups: the third-party organizations that reportedly spent $1 million on anti-NDP attack ads.

Big business in the province would appear to believe war-room operatives hold sway. Kukucha’s client list has tripled in the years since 2013, to 29, compared to the four years leading up to the last election. Brad Zubyk, his partner at Wazuku, saw a nine-fold increase in clients, reaching 42. Dimitri Pantazopoulos, Clark’s former principal secretary, and one of the most important members of her 2013 campaign team is one of the province’s busiest lobbyists.

Pantazopoulos, who’s been lionized for being the only pollster in B.C. to accurately predict Clark’s surprise majority, advertises his links to the premier on the site of the firm where he’s a partner, Maple Leaf Strategies. He notes his “extensive research into public attitudes” guided Clark’s “strategy and messaging,” contributing to her win. After serving 10 months as Clark’s principal secretary, he was given the post of assistant deputy minister of intergovernmental relations and trade in February 2012. Fifteen months later, he left that job to join the campaign, and afterward opened an office a few floors beneath the premier’s in a small, waterfront building in Vancouver.

There he earned a reputation as hard-working and sharp-elbowed lobbyist—yet reportedly stayed on as the B.C. Liberals’ pollster. Emile Scheffel, a Liberal spokesman, would say only that the party uses “a few different vendors,” outside the election writ period, and refused to say whether they include Pantazopoulos; Pantazopoulos himself declined comment. But seven weeks after the 2013 campaign ended, MLAs listed in public disclosures as lobbying targets included 70 per cent of the Liberal caucus, including the most senior members of government: Premier Clark, Deputy Premier Rich Coleman (who was co-chair of the 2013 campaign), Finance Minister Mike de Jong and their staffs.

Pantazopoulos’s client list includes key sponsors of the Liberals’ most recent convention, including Johnson & Johnson; the U.S. pharmaceutical giant hired the Liberal strategist to help them win a provincial procurement for the Nicorette and Nicoderm products the B.C. government provides free to those quitting smoking in the province. Pantazapolous also secured a significant victory for Uber. The Clark government’s decision to allow the embattled ride share company—currently facing allegations of corporate misdeeds, workplace discrimination, sexual harassment and questionable leadership—to begin operating in B.C. by December became a key plank in the Liberal platform. Ridesharing “provides job opportunities for British Columbians,” it notes, while giving consumers “choice in how they travel.”

Most notable, however, was the victory Pantazopoulos delivered to another Liberal convention supporter, Progressive Waste Solutions/BFI, which has donated $339,000 to the Liberals in the last four years. Pantazopoulos was hired to help the multinational garbage hauler persuade the province to kill a Metro Vancouver bylaw barring garbage from being trucked out to U.S. landfills, where haulers dodge bans on recyclables and pay cheap disposal fees. All 23 Metro region communities endorsed the restriction. But in October of 2014, three weeks after the Liberal party accepted the hauling company’s $22,000 donation, the government overturned the bylaw, basing the decision on industry fears it would create a monopoly on waste management.

While unfettered donations like these are considered business as usual in B.C., they’ve been banned by most major governments west of Russia (the list includes some of the most corrupt nations on the planet—Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Syria). Most also ban foreign, corporate and union donations. In B.C., however, any person or corporation or union can donate as much money as they want, as often as they want, from anywhere in the world. The one and only rule bars charities from donating to political parties. Last year, the B.C. Liberals raised twice more than any other ruling party in any other province, including twice what the ruling Liberals did in Ontario, a province with three times the population and four times the head office count.

One whistleblower, who is cooperating with the RCMP investigation into lobbying pratices, says he was “totally corrupted,” by B.C.’s entrenched pay-to-play culture. He says there is “no limit” to the emails requesting tens of thousands of dollars for cash-for-access fundraisers, golf tournaments, and dinners with the premier and senior cabinet members; the long-time lobbyist tells Maclean’s it is well-known in the industry that if you do not donate when asked, the party in power will shut you out. The goal of the game is delivering wins to clients, which becomes next to impossible when the doors of power are shut.

Former premier Gordon Campbell’s long-serving chief of staff, Martyn Brown, describes this system of “influence-buying” as “chronically deceitful” and “coercive to the core.” And it has also opened the door wide, other critics say, to global capital on a massive scale.

The Liberal party has been pulling in donations from oil giants from Malaysia and Singapore who happen to be seeking government approvals for LNG projects; from Texan oil companies seeking provincial pipeline approvals; from the world’s biggest fish farms seeking marine tenures (some in threatened marine ecosystems, like Clayoquot Sound), plus a long list of numbered and shell companies of obscure origin.

On a single November day last year, the Liberals raised $1.6 million, roughly half from two families who are major property developers in the province (eight of the top ten donors to the Liberals this year are involved in development and construction). Even the Chinese government has kicked in to the B.C. Liberal campaign fund, through the Bank of China, China Radio International and the Kailuan Group, a state-run coal company, which has given the party $60,000. In 2015, the year it was incorporated, the Vancouver China Cultural Centre, which aims to increase mutual understanding between China and Canada, gave the Liberals $10,000. VCCC’s stated aims include providing “media support, and image campaigns” to help “Chinese brands shine in North America,” according to its website. In 2016, one year after Beijing’s Modern Investment Group gave the Liberals $25,000 (its only donation to the party), it was announced that Modern was part of the consortium that bought a five-hectare parcel of land in Vancouver, one of the richest public land purchases in B.C. history.

Why the Liberals appear unfazed by the horrific optics of all this is an open question. Clark in particular built her political brand on the kind of populist savvy gained in her previous life as an open-line radio host. One reason might be that their main opponent has been playing the same game—albeit with less proficiency. Although the NDP has six times introduced legislation that would ban foreign and union donations, the party continues to accept such money (only the Greens refuse it). The Liberals believe this neutralizes the New Democrats; and it explains why they chose to release their biggest ammo on the day of the leader’s debate, when they announced that the NDP had received hundreds of thousands of dollars from the United Steelworkers, which has also been paying the salary of a few of the party’s campaign staff.

By taking big donations from organized labour, Horgan has handed Clark “a lasso to drag him down into the same fundraising muck,” says Nagata, adding that Clark just needs to keep repeating the message that the NDP’s hands are dirty. “From there it’s a short step to ‘all politicians are the same,’ and ‘what does one vote matter?’ The strategy is not meant to absolve Clark, but rather to demotivate her opponents.”

Nagata sees parallels to what U.S. President Donald Trump’s camp did to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton last fall: “By calling her “Crooked Hillary” they created a moral equivalency that neutralized Trump’s character flaws while suppressing the Democratic vote.” Clark’s team knows that to win, it needs turnout to remain low, in the neighbourhood of last election’s 55 per cent.

People within the party seem more concerned with the money than the PR fallout. One high ranking B.C. Liberal, speaking on condition of anonymity, explained: “Donors don’t care,” about the bad press, which may also suggest whose voice matters—and it’s not media’s. One of the Liberal campaign’s top communications strategists told Maclean’s the party “literally [doesn’t] care what any [media] outlet says, with the possible exception of Global” And their interest in the TV newscast, they added, was “marginal.”

If that sounds arrogant, consider that the $36 million the Liberals have raised since the last election allows them to repeatedly wrap commuter dailies with paid ads made to look like a front-pages touting Clark as “the only leader to protect jobs in B.C.” They can buy direct access to the newsfeeds of voters their digital team identify as receptive to their messaging. Indeed, they’ve been running campaign ads since summer. In advance of the May 9 election, the government suddenly doubled its ad budget, blanketing airwaves during the NHL playoffs and the Academy Awards with spots promoting the Liberal budget. The taxpayer-funded campaign was so overtly partisan that B.C.’s auditor general intervened with with a warning.

Meanwhile, the party’s team of paid, full-time field organizers has reportedly been working swing ridings for several years. The NDP, which has raised $10.5 million, a little more than a quarter of the B.C. Liberal booty, has, by comparison, been running a significant operating deficit every month, missing fundraising targets, shelving pre-election planning. They have governed B.C. for just 13 years.

RELATED: Does John Horgan have the stuff to beat Christy Clark?

Not that New Democrats are strangers to the revolving door between party roles and lobbying. In the last election, which the New Democrats looked likely to win, at least three high-profile lobbyists played key roles in the NDP campaign: Brad Lavigne and Jim Rutkowski at Hill and Knowlton Strategies, and Marcella Munro at Earnscliffe. Prior to the campaign, Hill and Knowlton, which had previously donated $72,000 to the Liberals suddenly turned off the tap, donating $14,000 to the NDP and nothing to the Liberals.

And if the game is really rigged, asks one Liberal strategist, speaking on background, “then why hasn’t media or the opposition found any examples of real corruption?” The answer, he says, “is you can’t find any. There is none.” Indeed, the government has never been sanctioned for any of the allegations of conflict of interest. There is nothing barring corporations from donating to the party. And provincial Liberal strategists insist donations have no influence on policy, procurements or licensing.

But David Eby, a lawyer and rising force in the NDP caucus, says undue influence is nearly impossible to prove, which underlines the need for iron-clad rules: “Can I prove that the $50,000 donation to the B.C. Liberals made by the director of Paragon, a gaming company, while bidding for a casino license influenced the decision to grant them the bid? No, I can’t. Did Paragon win the bid? Yes. Is it problematic? Does it look bad? Yeah—it stinks” (both Paragon Gaming and former Paragon director T. Richard Turner, who made the donation to the Liberals via his family’s real estate investment firm, Titanstar Management, declined to comment for this story).

It’s certainly hard, says Nagata, to look at the treatment of Imperial Metals Corp.—the owner of a B.C. mine-tailings pond that spilled billions of gallons of toxic sludge in 2014—independent of the $1.5-million that controlling shareholder Murray Edwards has donated to and raised for the B.C. Liberals. The Mount Polley Mining Corp., an Imperial subsidiary, was neither fined nor sanctioned for the environmental disaster, and was subsequently allowed to open a second mine. A few weeks ago, B.C.’s environment ministry quietly announced that Mount Polley can now pipe its tailings directly into Quesnel Lake, a drinking source for a Cariboo Region First Nations community. Minister Mary Polak has said the decision was made by neutral civil servants based on science. “These decisions do not cross any politician’s desk,” she told the CBC on April 18.

Even some long-time Liberal operatives are furious. Paul Doroshenko, a Vancouver lawyer and Liberal volunteer who worked on former premier Gordon Campbell’s campaigns believes his party has “abandoned its commitment to a regulated market economy, and become a club for donors to the B.C. Liberal Party.” Clark “sold us out,” Doroshenko goes on. “Regular people have been shut out.”

Whatever the truth, the Liberals are playing a dangerous game in a populist province where chequebook issues have determined political choices. Their platform, an exhaustive recall of all of Clark’s triumphs with little in the way of new promises, isn’t helping the party. The NDP put up a stark contrast with its pledge to balance the books while introducing a raft of seemingly popular reforms—planks that have more or less withstood scrutiny.

These include significantly hiking the minimum wage, a move that a recent poll suggests enjoyed the support of 75 per cent of British Columbians; banning big money from politics (71 per cent support); banning B.C.’s grizzly bear hunt, (91 per cent); and eliminating health care premiums. There are also a couple of goodies meant to appeal to non-traditional NDP voters, like a promise to eliminate bridge tolls, which disproportionately hurt the suburbs. Martyn Brown, the former Campbell aide and principal architect of the B.C. Liberals’ first three winning election platforms, calls the NDP’s plan a “blueprint” to building a “better B.C.”

None of this may matter. Days out from the vote, the Liberals have every chance of forming another government, possibly with the help of the Greens acting as spoilers. But if they do stumble, and the New Democrats somehow overcome the millions spent to keep them at bay, the B.C. Liberals will have only themselves to blame. Somewhere, Linda Higgins will be smiling.

WATCH MORE: The first B.C. leaders debate