Boxing as a ‘living metaphor of the struggle for equality’

George Elliott Clarke, Canada’s poet laureate, on the importance of sports in the lives of black Canadians

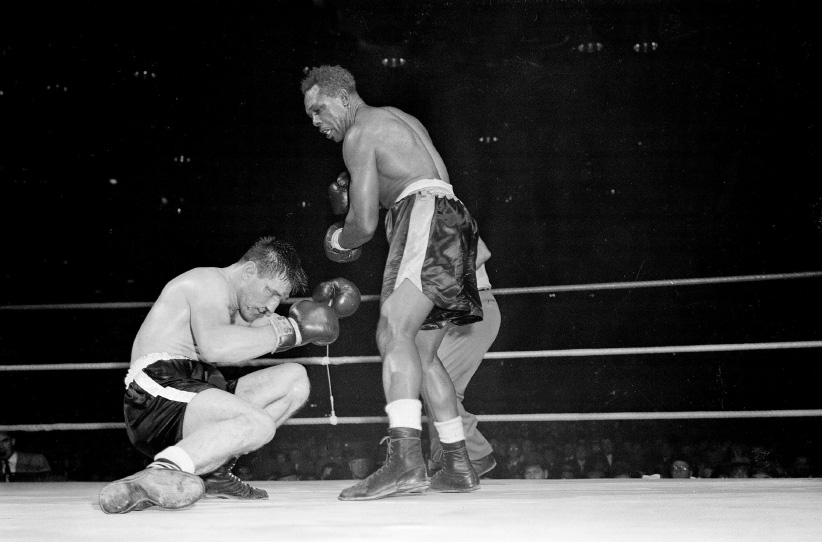

Canadian challenger Yvon Durelle is down in 11th round of Light-Heavyweight title fight just before losing to champion Archie Moore in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Dec. 10, 1958. (AP/CP)

Share

This post originally appeared on Sportsnet.

Throughout Black History Month, Sportsnet will release weekly features examining sport’s connection to black communities in Canada, and celebrating the lives and accomplishments of black athletes, coaches and executives.

George Elliott Clarke, Canada’s seventh Poet Laureate and one of this country’s finest literary voices, was born in Windsor, Nova Scotia, and has written extensively about the black communities of the Maritimes. We met at a pub near his home in the east end of Toronto to talk about the importance of sports in the lives of black Canadians—particularly out on the East Coast. That and suavity.

Q: I’m going to start with a shamefully broad question and hopefully we can narrow the focus as we go: What role did sports play in the black communities of the Maritimes, particularly in your home province of Nova Scotia, when you were growing up?

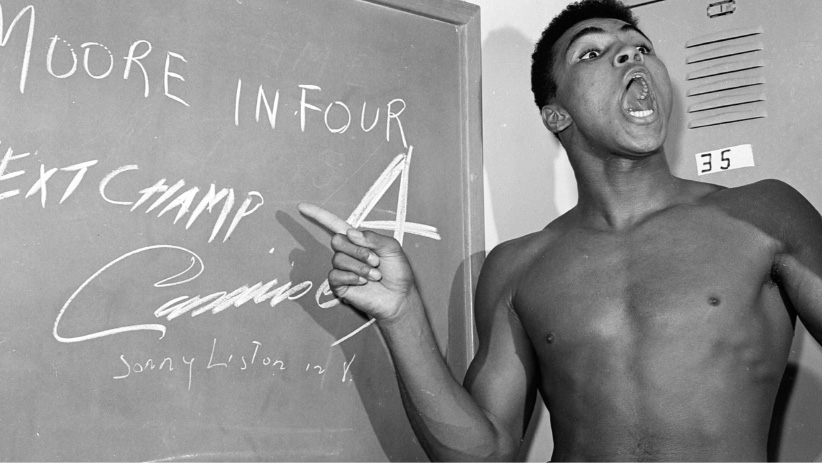

A: I think the first sports figures who would’ve been important for me—and maybe, I would suggest, important for the black community in Nova Scotia—would have been boxers. We have a strong history of boxing in the Maritimes, in Nova Scotia. One of my own relatives is Clyde Gray, who was a Commonwealth champion. I can’t even say I’ve ever met him, but to know he’s my cousin was important for me—just as important as being able to say that my great-aunt Portia White was a renowned contralto and internationally famed singer back in the ’30s and ’40s. I had this singer on my father’s side and this boxer on my mother’s, both of them representing achievement. I think in my community, as relatively small as it was, [there was importance placed on] figures like Muhammad Ali, Archie Moore and the boxers from Nova Scotia: George Dixon, who fought under the moniker of “Little Chocolate” and whose name was very much remembered in Nova Scotia; the so-called “Boston Tar Baby” Sam Langford.

Q: Oh, god.

A: Yeah, the moniker is horrible. But he could’ve been a heavyweight champion of the world. He was such a formidable boxer that Jack Johnson, who was the first black heavyweight champion, refused to fight him, so he never had a shot at that title. But boxing historians agree that would’ve been a huge battle, if those two men had ever gotten together in the ring.

Q: What was it about boxers that made them stand out? Was it that it was the first sport where a black man could be champion of the world?

A: The early 20th Century was probably the high tide of global white supremacy—I’m going to call it that because that’s how people thought of it—and to be specific, Anglo-Saxon supremacy: The idea that white Anglo-Saxon Protestants were at the top of the world, representing the highest achievement possible for all of humanity, with Darwin’s theories being used to prop up this belief. And so, when Jack Johnson beat Jim Jeffries in 1910, it caused race riots. Black men were lynched in the United States because [Johnson’s win] was understood to be a symbolic defeat of this ideology of white supremacy. Black men around America paid a price for the symbolic importance of Johnson’s victory. And then Johnson rubbed salt in the wound by openly consorting with white women, escorting them here and there in his expensive car, and essentially living this fantasy of not just black equality, but black superiority—at least in terms of the physique and brawn he obviously represented.

Johnson’s victory didn’t overturn racism, but it certainly served notice that there could be more to come, more challenges [to white supremacy] in more fields. And so his symbolic victory—keep in mind it was only symbolic—still was galvanizing. I think it remains a touchstone for athletes and intellectuals and cultural workers, if we bother to remember history at all.

But getting back to Nova Scotia, we had those boxers—Sam Langford and George Dixon and then when I was a boy, the Downey Clan and my cousin, Clyde Gray. And Nova Scotia in general was a place where race relations got played out in the boxing arena. Most definitely.

Q: As in, there’s a fight, it’s a black guy against a white guy, and the black fans are all cheering for the black guy and the white fans are all cheering for the white guy?

A: Yup, exactly. I was visiting my hometown in 2010 or 2012. There are a couple of four-way stops in the town, and I happened to stop at one. I look over at the lamppost and there was this photocopied piece of paper stapled to the lamppost. [On it there was] a black-and-white photograph of a black guy and a white guy and the slogan was “Fight Tonight” at some arena in Windsor. I wasn’t able to hang around to go to the fight, but I said to myself, “That place is going to be packed; everybody’s going to be going there. And people, as late as 2012, are going to be having these fantasies of ‘Can that white guy deck that black guy a few times?’ and the other way around.”

Boxing remains an important living metaphor of the struggle for equality. I think this is particularly true in Canada. The way racism works in Canada, it’s very subtle. You may feel you’re a victim of racism or have experienced racism, but you can’t necessarily prove it—unless you get a [white] friend to go check out that rental, go check out that job, whatever. Unless you’re willing to really dig to prove you’re a victim of racism, it might be difficult to do that. And so what you’re dealing with then is feeling, it’s emotion. And what do you do with all that frustration—the frustration that you were shortchanged over here and treated impolitely over there and not trusted over there? Well, if you’re not interested in slugging someone and ending up in prison or getting beat to a pulp yourself, one possibility is to watch a fight. Especially if it’s black versus white. Then you’ve got this allegorical battle going on that you can invest in emotionally.

So, as a boy, a youth, a young man in Nova Scotia, whenever a major fight was happening in Halifax, everyone’s going to drop everything and go watch, and be talking about it the next day. If it’s a major international fight, Ali or “Iron” Mike Tyson, we’re going to drop everything and sit and watch that fight. Again, partly because of the psychological need to have the emotional battle, so to speak, fought out in front of us.

Q: Do those fights accomplish anything tangible? They’ve got the symbolic weight—occasionally the symbolic victory—and the catharsis, but do they help to solve any of the larger problems faced by black people or are they just a pressure-release valve that makes it easier to endure being stuck in the same unjust situation?

A: The answer is yes and no. A symbolic victory is still a victory. I have felt uplifted when an athlete or a team I have emotionally invested in triumphs, and I think we’ve all had that feeling. In terms of race, there’s also a strengthened sense of empowerment [in seeing those victories]. You can look at these achievers and say, “If so-and-so can overcome that to win, then maybe I can [overcome and succeed] in my own particular arena.” I feel lucky to live at a time when the dominant tennis players are Venus and Serena Williams. And to have lived through the success of a whole slew of boxers and feel I could invest emotionally and psychologically in their victories, and identify with them in their struggles. (Unless it’s something ridiculous or potentially criminal—then they’re on their own.) But I’ll try to derive some encouragement for myself to achieve excellence and strive and to “win” and to be encouraging to others. Those symbols are encouragements for one to struggle through and try to succeed. Sports are never just sports, we all know that. You’re always carrying the flag in some way, shape or form.

Q: What role do you think sports play in Canada’s black communities today?

A: My immediate reaction is that it’s a good thing that some black youth can now aspire to think of themselves as being a Raptor, an NHL player, a Blue Jay. The possibility of being a star, getting some money, getting that respect and adoration, giving something back to the community. I think it’s great that youth can now really, legitimately dream and aspire—although I hope that folks will have Plan Bs to fall back on.

I still think that there’s some kind of psychological investment in black athletes carrying the flag for “us” at times. So, sports [remains a] metaphor for struggle and triumph and flair. I haven’t talked about that, but flair, suavity, carrying yourself with grace, being respectable, wearing those clothes, those shoes. I’m not into the whole commercial thing, but I can understand the appeal of someone rocking those shoes and that particular haircut and setting a standard—a fashion standard, a standard of comportment. I think it’s marvellous that black Canadians can now aspire to set those kind of standards and make those kind of waves in the world—and it’s great for Canadian identity in general. To strut a little bit, that’s good for everybody. Everybody can strut a little bit, feel better walking down the street, head held high, shoulders back, locomotion, locomotion with style. I think those possibilities exist more than ever, and we should take advantage of those moments to not just wave a flag but brandish it.

Q: Those moments of overt celebration—after a goal, for example—are often the ones picked out and blown out of proportion to get black athletes in trouble.

A: I hear you. Things like that have been said about the Williams sisters, Ali…

Q: Pretty much every prominent black athlete ever.

A: And you know what? Bring it on. Keep on being a star in your own right. Keep on defining yourself. Don’t be defined by others. And redefine the sport in terms of your expertise, in terms of your talent, in terms of your strength, in terms of your flair. Make it interesting. Make it something that people want to watch. Why not? Bring it. Don’t hold back. There’s going to be somebody who likes it, chronicles it. Sport is cultural. What the star athlete does helps to define the culture. What the star athlete does on a Canadian team, especially if he or she is Canadian, helps define Canadian-ness. Why hold back?

Q: You’ve talked about the way sports help shape and empower a sense of identity—as a black man, as a Canadian, all the various things someone might be. I’m wondering if, as a fan, you ever feel those parts of yourself meshing, colliding or splintering, and how those moments work.

A: One is always wearing a couple of hats, depending on the situation. I suppose the “dilemma” might come up if I see a black athlete from the U.S. squaring off against a white Canadian athlete. Who do I want to identify with? I certainly will not and cannot say that race determines how I see competition. I’m certainly aware of how race plays into the way others see and portray competition some times, but I don’t have to invest in it that way myself. Unless it’s boxing. [Laughs.] And I’ll blame my childhood for that.