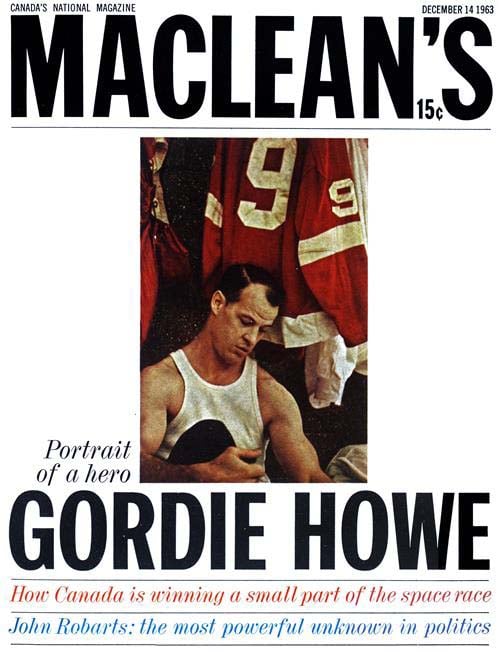

Gordie Howe, hero. A Peter Gzowski report: Dec. 14, 1963

Once in a lifetime there may appear in a sport one player so gifted and dedicated that he becomes a heroic figure of his time. Here is a new look at the man who now fills that role

Share

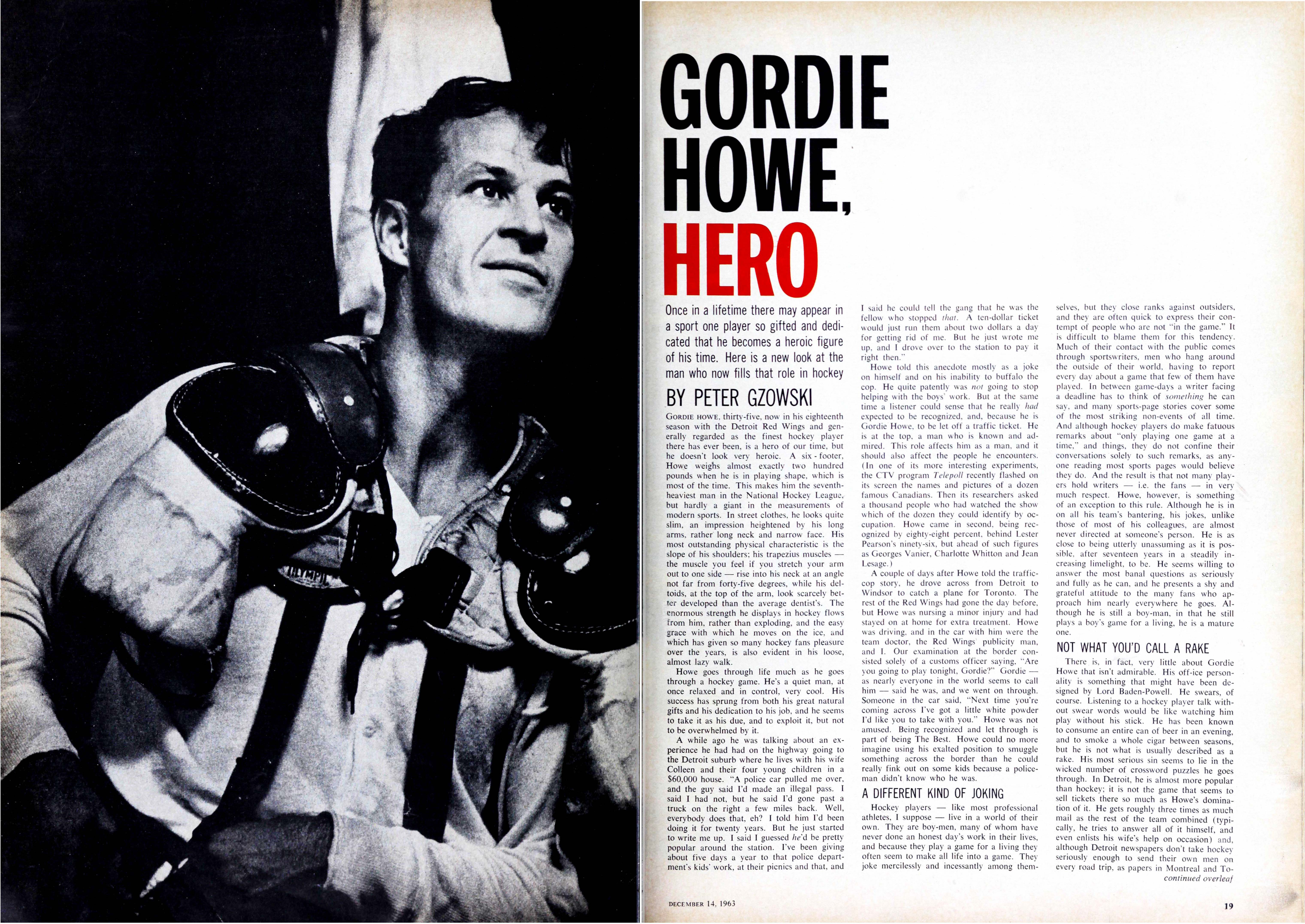

GORDIE HOWE, thirty-five, now in his eighteenth season with the Detroit Red Wings and generally regarded as the finest hockey player there has ever been, is a hero of our time, but he doesn’t look very heroic. A six-footer, Howe weighs almost exactly 200 pounds when he is in playing shape, which is most of the time. This makes him the seventh-heaviest man in the National Hockey League, but hardly a giant in the measurements of modern sports. In street clothes, he looks quite slim, an impression heightened by his long arms, rather long neck and narrow face. His most outstanding physical characteristic is the slope of his shoulders; his trapezius muscles — the muscle you feel if you stretch your arm out to one side — rise into his neck at an angle not far from 45 degrees, while his deltoids, at the top of the arm, look scarcely better developed than the average dentist’s. The enormous strength he displays in hockey flows from him, rather than exploding, and the easy grace with which he moves on the ice, and which has given so many hockey fans pleasure over the years, is also evident in his loose, almost lazy walk.

Howe goes through life much as he goes through a hockey game. He’s a quiet man, at once relaxed and in control, very cool. His success has sprung from both his great natural gifts and his dedication to his job, and he seems to take it as his due, and to exploit it, but not to be overwhelmed by it. A while ago he was talking about an experience he had had on the highway going to the Detroit suburb where he lives with his wife Colleen and their four young children in a $60,000 house.

“A police car pulled me over, and the guy said I’d made an illegal pass. I said I had not, but he said I’d gone past a truck on the right a few miles back. Well, everybody does that, eh? I told him I’d been doing it for 20 years. But he just started to write me up. I said I guessed he’d be pretty popular around the station. I’ve been giving about five days a year to that police department’s kids’ work, at their picnics and that, and I said he could tell the gang that he was the fellow who stopped that. A 10-dollar ticket would just run them about two dollars a day for getting rid of me. But he just wrote me up, and I drove over to the station to pay it right then.”

Howe told this anecdote mostly as a joke on himself and on his inability to buffalo the cop. He quite patently was not going to stop helping with the boys’ work. But at the same time a listener could sense that he really had expected to be recognized, and, because he is Gordie Howe, to be let off a traffic ticket. He is at the top, a man who is known and admired. This role affects him as a man, and it should also affect the people he encounters. (In one of its more interesting experiments, the CTV program Tele poll recently flashed on its screen the names and pictures of a dozen famous Canadians. Then its researchers asked a thousand people who had watched the show which of the dozen they could identify by occupation. Howe came in second, being recognized by eighty-eight percent, behind Lester Pearson’s ninety-six, but ahead of such figures as Georges Vanier, Charlotte Whitton and Jean Lesage.)

A couple of days after Howe told the traffic cop story, he drove across from Detroit to Windsor to catch a plane for Toronto. The rest of the Red Wings had gone the day before, but Howe was nursing a minor injury and had stayed on at home for extra treatment. Howe was driving, and in the car with him were the team doctor, the Red Wings’ publicity man, and I. Our examination at the border consisted solely of a customs officer saying, “Are you going to play tonight. Gordie?” Gordie — as nearly everyone in the world seems to call him — said he was, and we went on through. Someone in the car said, “Next time you’re coming across I’ve got a little white powder I’d like you to take with you.” Howe was not amused. Being recognized and let through is part of being The Best. Howe could no more imagine using his exalted position to smuggle something across the border than he could really fink out on some kids because a policeman didn’t know who he was.

A different kind of joking

Hockey players — like most professional athletes, I suppose — live in a world of their own. They are boy-men, many of whom have never done an honest day’s work in their lives, and because they play a game for a living they often seem to make all life into a game. They joke mercilessly and incessantly among themselves but they close ranks against outsiders, and they are often quick to express their contempt of people who are not “in the game.” It is difficult to blame them for this tendency. Much of their contact with the public comes through sportswriters, men who hang around the outside of their world, having to report every day about a game that few of them have played. In between game-days a writer facing a deadline has to think of something he can say, and many sports-page stories cover some of the most striking non-events of all time. And although hockey players do make fatuous remarks about “only playing one game at a time,” and things, they do not confine their conversations solely to such remarks, as anyone reading most sports pages would believe they do. And the result is that not many players hold writers — i.e. the fans — in very much respect. Howe, however, is something of an exception to this rule. Although he is in on all his team’s bantering, his jokes, unlike those of most of his colleagues, are almost never directed at someone’s person. He is as close to being utterly unassuming as it is possible, after 17 years in a steadily increasing limelight, to be. He seems willing to answer the most banal questions as seriously and fully as he can, and he presents a shy and grateful attitude to the many fans who approach him nearly everywhere he goes. Although he is still a boy-man, in that he still plays a boy’s game for a living, he is a mature one.

Not what you’d call a rake

There is, in fact, very little about Gordie Howe that isn’t admirable. His off-ice personality is something that might have been designed by Lord Baden-Powell. He swears, of course. Listening to a hockey player talk without swear words would be like watching him play without his stick. He has been known to consume an entire can of beer in an evening, and to smoke a whole cigar between seasons, but he is not what is usually described as a rake. His most serious sin seems to lie in the wicked number of crossword puzzles he goes through. In Detroit, he is almost more popular than hockey; it is not the game that seems to sell tickets there so much as Howe’s domination of it. He gets roughly three times as much mail as the rest of the team combined (typically, he tries to answer all of it himself, and even enlists his wife’s help on occasion) and, although Detroit newspapers don’t take hockey seriously enough to send their own men on every road trip, as papers in Montreal and Toronto do for their teams, a minor skate cut he suffered this fall was a daily story, with pictures of his foot and lengthy bulletins from the medical department.

For all his fame, Howe is still astonishingly shy. The nervous blinking of both his eyes that is apparent when he is interviewed on television is much less evident in private moments, and when he is relaxing in a pinochle game with teammates it all but disappears. Part of his shyness he covers with his warm, disarming wit, and it is evident that all the people who are in frequent contact with him, from his bosses at the Red Wings to his partners in business to his neighbors’ children, whom he sometimes smuggles into the Olympia to go skating, like him as much as they respect his ability to play hockey.

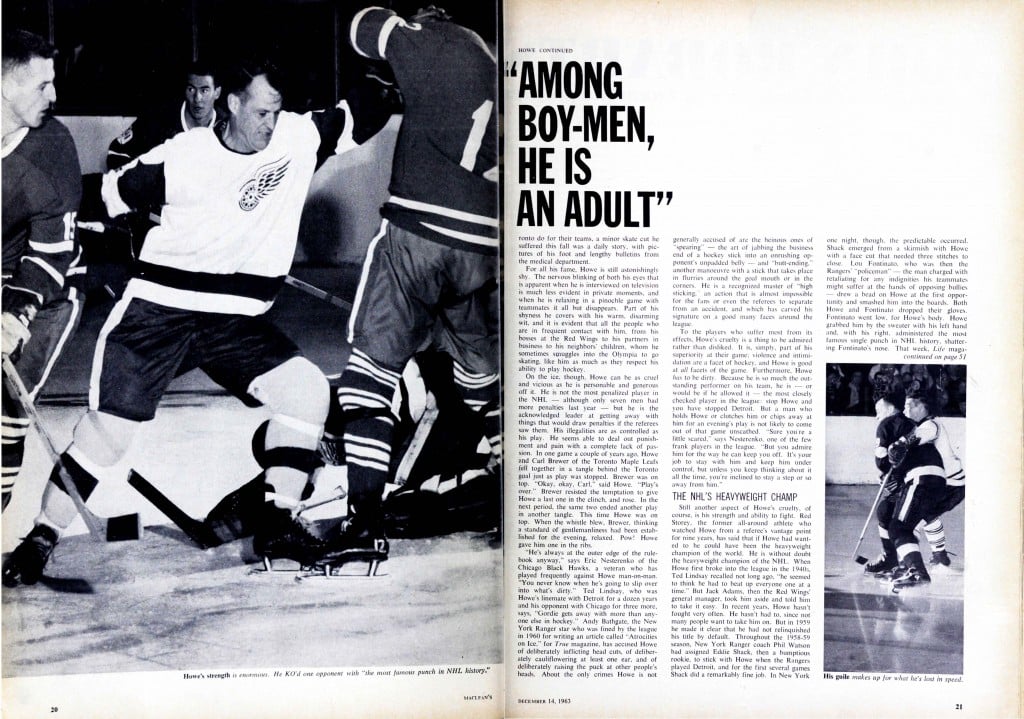

On the ice, though, Howe can be as cruel and vicious as he is personable and generous off it. He is not the most penalized player in the NHL — although only seven men had more penalties last year — but he is the acknowledged leader at getting away with things that would draw penalties if the referees saw them. His illegalities are as controlled as his play. He seems able to deal out punishment and pain with a complete lack of passion. In one game a couple of years ago, Howe and Carl Brewer of the Toronto Maple Leafs fell together in a tangle behind the Toronto goal just as play was stopped. Brewer was on top. “Okay, okay, Carl,” said Howe. “Play’s over.” Brewer resisted the temptation to give Howe a last one in the clinch, and rose. In the next period, the same two ended another play in another tangle. This time Howe was on top. When the whistle blew. Brewer, thinking a standard of gentlemanliness had been established for the evening, relaxed. Pow! Howe gave him one in the ribs.

“He’s always at the outer edge of the rulebook anyway,” says Eric Nesterenko of the Chicago Black Hawks, a veteran who has played frequently against Howe man-on-man. “You never know when he’s going to slip over into what’s dirty.” Ted Lindsay, who was Howe’s linemate with Detroit for a dozen years and his opponent with Chicago for three more, says, “Gordie gets away with more than anyone else in hockey.” Andy Bathgate, the New York Ranger star who was fined by the league in 1960 for writing an article called “Atrocities on Ice,” for True magazine, has accused Howe of deliberately inflicting head cuts, of deliberately cauliflowering at least one ear, and of deliberately raising the puck at other people’s heads. About the only crimes Howe is not generally accused of are the heinous ones of “spearing” — the art of jabbing the business end of a hockey stick into an onrushing opponent’s unpadded belly — and “butt-ending,” another manoeuvre with a stick that takes place in flurries around the goal mouth or in the corners. He is a recognized master of “high sticking,” an action that is almost impossible for the fans or even the referees to separate from an accident, and which has carved his signature on a good many faces around the league.

To the players who suffer most from its effects, Howe’s cruelty is a thing to be admired rather than disliked. It is, simply, part of his superiority at their game; violence and intimidation is a facet of hockey, and Howe is good at all facets of the game. Furthermore. Howe has to be dirty. Because he is so much the outstanding performer on his team, he is — or would be if he allowed it — the most closely checked player in the league: stop Howe and you have stopped Detroit. But a man who holds Howe or clutches him or chips away at him for an evening’s play is not likely to come out of that game unscathed. “Sure you’re a little scared,” says Nesterenko, one of the few frank players in the league. “But you admire him for the way he can keep you off. It’s your job to stay with him and keep him under control, but unless you keep thinking about it all the time, you’re inclined to stay a step or so away from him.”

The NHL’s heavyweight champ

Still another aspect of Howe’s cruelty, of course, is his strength and ability to fight. Red Storey, the former all-around athlete who watched Howe from a referee’s vantage point for nine years, has said that if Howe had wanted to he could have been the heavyweight champion of the world. He is without doubt the heavyweight champion of the NHL. When Howe first broke into the league in the 1940s, Ted Lindsay recalled not long ago, “he seemed to think he had to beat up everyone one at a time.” But Jack Adams, then the Red Wings’ general manager, took him aside and told him to take it easy.

In recent years, Howe hasn’t fought very often. He hasn’t had to, since not many people want to take him on. But in 1959 he made it clear that he had not relinquished his title by default. Throughout the 1958-59 season, New York Ranger coach Phil Watson had assigned Eddie Shack, then a bumptious rookie, to stick with Howe when the Rangers played Detroit, and for the first several games Shack did a remarkably fine job. In New York one night, though, the predictable occurred. Shack emerged from a skirmish with Howe with a face cut that needed three stitches to close. Lou Fontinato, who was then the Rangers’ “policeman” — the man charged with retaliating for any indignities his teammates might suffer at the hands of opposing bullies — drew a bead on Howe at the first opportunity and smashed him into the boards. Both Howe and Fontinato dropped their gloves. Fontinato went low, for Howe’s body. Howe grabbed him by the sweater with his left hand and, with his right, administered the most famous single punch in NHL history, shattering Fontinato’s nose. That week, Life magazine ran one full-page photo of Fontinato in the hospital, his nose a wreck and his eyes swollen and bruised, and another of Howe in the dressing room, with his shirt off and his muscles rippling. In a nice summary of the importance of a man playing a body collision sport like hockey not only being tougher than his opponent but appearing to be tougher, the Rangers’ coach Watson said later that the heart went out of his team not when Howe threw his mighty punch but when the two contrasting photos appeared for the world to see: the Red Wings’ cool Goliath had made a patsy out of their champion. The Rangers finished a bad last that year.

But even Fontinato, a likeable ruffian who has unfortunately been lost to hockey through a serious injury, could not hold Howe’s victory over him as a personal grudge. Scott Young, then writing his excellent sports column for the Toronto Globe and Mail, happened to be present when Howe and Fontinato met for the first time off the ice after their match. “I guess you know Gordie Howe.” Young said to Fontinato. “I guess so, but I’m not sure I should lower my hands to shake with him,” Fontinato said, and then smiled and did so.

“Baseball” goes one of the most common clichés in sports, “is a game of inches.” So is hockey. But in hockey the inches, since they are covered a lot more quickly, are not so evident to the casual observer. All the men who play in the NHL — the best hundred and twenty or so of the hundreds of thousands of Canadian boys who play hockey in every generation — have completely mastered the fundamentals of their game. By the time one of them has reached that plateau, he can skate, shoot, pass and check nearly as well as he is ever going to so that the only things that separate those who are going to remain journeymen from those who will rise to stardom are such natural qualities as physique, desire and what might be called hockey sense. Howe has all three in abundance, and in various combinations they have given him a tiny but real advantage over virtually every player in the NHL at virtually every department of the game.

He is so well co-ordinated that he could almost certainly play with the best at any sport he chose to take up. A few years ago, in fact, he became friends with a few of the professional baseball players who live in Detroit and, mostly for conditioning, he worked out with the Detroit Tigers occasionally. Buckv Harris, then manager of the Tigers, saw him in the batting cage one day, pounding balls out into the bleachers with the strongest of Detroit’s long-ball hitters, and was heard to remark that it would take only a few months to turn Howe into a regular in the big leagues. And Howe has been seen at a Red Wing practice standing beside the goal, holding his hockey stick like a baseball bat and knocking back many of the hardest shots his teammates tried to fire past him.

Howe’s co-ordination, however remarkable, probably does not set him so far apart from the average professional hockey player as his strength does. He can shoot a puck from near one goal and make it rise into the seats at the other end of the rink — an impossible feat for nearly anyone else in the league. One man whose shot comes close in speed to Howe’s, which has been measured at a little better than a hundred and twenty miles an hour, is Bobby Hull, the glamorous and exceedingly talented star of the Chicago Black Hawks and the man who may some day succeed to Howe’s mantle. (Significantly, Hull this year began wearing number 9 on his sweater, after having been 7 for his first six seasons: 9 is Howe’s number, and was also worn by Maurice Richard of Montreal, when Richard was the biggest name in hockey.) But for Hull to take his fastest shot he has to raise his stick three or four feet and slap the puck. Howe can move his stick only a foot or so and actually flick the puck away at close to his maximum speed. Another curious similarity between Howe, the old bull, and Hull, the young one, is that Howe has for years been the only man in the league who can change the position of his hands on the stick from his natural grip, right-handed, to his unnatural one, left, and still retain most of his power, and now Hull appears to he the second one — although Howe’s wrong-side shot is still stronger than Hull’s. This technique of switch-hitting, as it were, gives Howe an advantage of an inch or more over anyone who’s trying to check him. When he first broke into the league, in 1946, he played against Dit Clapper, who had stayed in the NHL for twenty years, a record Howe is almost certain to match. For all his age, Clapper still had surprising speed, and he was able to stay with most of the young forwards who came scooting in on him. One of the first times Clapper checked the young Howe, though, Howe changed his hands on his stick, thus putting his body between Clapper and the puck, and getting a clear shot on the Boston goal. “I think that’s when Dit decided he’d quit hockey,” Ted Lindsay says.

Except for his exceptional shot, Howe doesn’t move quickly on the ice. His motions are graceful and economical; he never seems to waste energy. As one result, he has not only played more NHL games than any other player in history (more than eleven hundred), but he has frequently been able to put in as much as forty-five minutes in a single game. Most forwards average perhaps twenty-five. Howe often comes off the ice exhausted, and he can lose as much as six pounds in a single game, but anyone watching him on the bench will notice that no matter how he droops when he first hits his seat, he always seems to be the first resting player to recuperate. In about half a minute, it seems, his head is up and he is studying the play as if thinking about what he can do during his next shift. Unfortunately for medical science, no one has yet tried to measure the source of Howe’s remarkable endurance. His counterpart in basketball, Bob Cousy of the Boston Celtics, now retired, was once discovered by some Massachusetts scientists to discharge ten times as much of an adrenal hormone called epinephrine as any other basketball player they tested. It would be fascinating to see if Howe has similar characteristics, or if he secretes an exceptional amount of another adrenal hormone, norepinephrine, which is associated with “aggression, anger and competitiveness,” and is sometimes called the hockey player’s hormone.

Physical gifts aside, Howe brings to hockey a fierce pride and dedication that would probably have made him excel at whatever line of work he’d chosen. As it is, he applies it to bowling and golf, at both of which he can beat any of the people he plays with. Whatever he does, he must win, and in hockey he’s been willing to work long hours to achieve his near perfection. In their early years, for instance, Howe and his linemate Lindsay used to stay at practice well after lesser luminaries of the Detroit team had gone to the showers, and work on special plays. Once they discovered that if the puck were shot into the other team’s corner at a certain angle it could be made to bounce out in front of the goal, but out of the goalie’s reach. Howe and Lindsay worked on this play for hours, until they were able to use it in games, and for a season or two Lindsay received dozens of apparently fluke breakaways by going straight at the goal while Howe shot the puck into the corner. Now, of course, every team in the league executes this play (usually most effectively on home ice, since all boards react differently).

Howe’s third talent seems, to some, almost supernatural. He appears to anticipate the puck — or his opponents — almost as if play gravitated toward him by some natural force. In fact, it is a result of many qualities: a thorough knowledge of the game, his ability to remain always in control of himself, and his high sense of timing. Hockey at the NHL level is not so much a matter of how you make your move — since so little separates the good players from the mediocre in their ability to make it — but when. With his graceful control, Howe can appear to the man checking him to be relaxed, but if that man gives him so much as half a step, Howe will seize on the instant to send or receive a pass or get away a shot. In the same way, he can sense a play developing, and without giving away his plans to the man on his back, move toward the place he knows the puck must come, or shake his check for the brief instant that he will be in the clear. Situations form and disintegrate so rapidly when a hockey game is flowing back and forth at full tilt that a split second’s advantage — an “inch” of ice — is all a player of Howe’s certainty needs to appear to be all by himself. (Another reason Howe gets the puck a lot, of course, is that his teammates give it to him as often as they can, as who would not?)

In the opinion of the people who ought to be able to judge best, Howe is now not quite as fast a skater as he was a few years ago (he never was as fast a breakaway skater as Maurice Richard), although he can still move pretty rapidly when he gets loose. If he’s lost anything in speed, though, he has more than made up for it in guile. Last season, when he led the league in scoring for the first time in five years (he did it five times in the Fifties), and led Detroit into a surprisingly close Stanley Cup final, Dave Keon, the young Toronto Maple Leaf star, remarked: “There are four strong teams in this league and two weak ones. The weak ones are Boston and New York and the strong ones are Toronto, Chicago, Montreal and Gordie Howe.”

Howe began to skate at about the age of five. He was the fifth of nine children of a family that had been farming in the district of Floral, Sask., in 1928 when Gordon was born. The family had moved to a two-story clapboard house on Avenue L North in Saskatoon when he was an infant. From the time he got his first pair of skates, he recalls, he spent most of his winters on ice, skating across a series of sloughs to get to school, or playing hockey outdoors. As a boy, he played goal, and he recalls that one teacher told him “if I ever moved out from between the pipes I’d never get anywhere in hockey.” (Howe thinks his season and a half as a goalie, holding his stick with one hand, has something to do with his ability to switch-hit as a pro.)

In the summers, young Gordie worked on farms around Saskatoon, putting in twelve-hour days, and, he says, eating five big meals a day. His father was nearly as strong as Gordie is today. Gordie remembers straining to hold up one end of a giant boulder they were lifting together, and his father muttering, “Come on, boy, don’t let me down.” He weighed two hundred pounds at sixteen. But talent bird-dogs from the professional hockey clubs had sniffed him out even before that. Fred McCrorry, a scout for the New York Rangers, talked him into going to the Rangers’ training camp at Winnipeg the summer he was fifteen.

The camp was a miserable experience for him. On the first day of practice, the boy who had been assigned as his roommate was injured and Howe was forced to spend the remaining weeks by himself. He was too shy to join in the general scramble at mealtime, and occasionally missed eating. Homesick, he went back to Saskatoon.

The next year, though, a Detroit scout named Fred Pinckney was able to talk him into trying the Red Wings’ camp at Windsor, Ontario, and Jack Adams signed him to a contract to play with the Red Wings’ Junior A farm team in Galt. Ontario. This was an “illegal” transfer, taking a western boy to an eastern team, and Howe was forced to spend his first year away from home as a pariah, allowed on the ice only in practice or exhibition games. (He did, in fact, play one league game, which the Galt Red Wings won but had to forfeit because of his participation.) His shyness affected his life in Galt, too. The Red Wings had enrolled him at the Galt Collegiate Institute and Vocational School. But, never a good student, he “took one look at the size of the campus and all those kids and decided not to go.” Instead, he got a job at Galt Metal Industries, and suffered through his lonely winter.

The next year, 1945, the Red Wings sent him to their U.S. Hockey League team in Omaha, Nebraska, where he scored twenty-two goals and convinced his bosses that he would be ready for the big team at eighteen.

In Omaha, Howe had been so shy that he used to leave the arena by the dressing-room window rather than face the ardent fans outside the door — particularly a very ardent girl fan the Omaha players called SpaghettiLegs. The Red Wings hit on a good antidote. They gave him, as a roommate, Ted Lindsay, a cocky, aggressive youngster from Kirkland Lake, Ont., who went on to become the game’s third leading goal scorer, behind only Howe and Richard. These two vastly different personalities quickly became good friends and earnest allies in the Detroit cause, and to this day are mutual admirers.

Howe was slow to start in the NHL, although he scored a goal in his first game, and before his first season was over had won a fight with Maurice Richard and lost his front teeth. In his first three years in the NHL, he scored only thirty-five goals, but he hit his stride quickly after that, matching his total of thirty-five in his fourth season alone. Since then he has failed to score thirty goals only three times, and for one of those seasons he was named the most valuable player in the league anyway. For the last fourteen years, he has completely dominated the statistics of the NHL, never being worse than sixth in league scoring, making eight first and five second allstar teams, being judged the most valuable player to his team six times. When he finally scored his five hundred and forty-fifth goal in league play this year and passed Maurice Richard’s lifetime total, he completed a clean sweep of all the significant scoring records: most goals, most assists and, naturally, most points. Since he intends to play at least two more seasons after this one, he will undoubtedly run his record totals well out beyond the reach of anyone now in sight.

Hockey has been immensely good to Howe — almost as good as he has been to it. Through the years, he has suffered far fewer than his share of injuries. (Although he has had serious ones. In the Stanley Cup finals in 1950 he hit the boards after a check by Toronto’s Ted Kennedy and slumped unconscious to the ice. For two days he was close to death, and an operation was needed to relieve the pressure on his brain. In the season of 1952-53, he broke his right wrist around Christmas time. But he had a cast put on, played the next game and went on to win the scoring championship. In eighteen seasons, he’s missed only forty-one games.) He is now being paid thirty-five thousand dollars a year by the Red Wings, and his outside activities may well bring him nearly as much again. He is a partner in a commercial rink in Detroit called Gordie Howe’s Hockeyland, and in another firm that sells ice-cream machines. He is known as a cool negotiator. He endorses a cornucopia of products from milk to shirts. This year, Campbell Soup has brought out a little hard-cover book called Hockey . . . Here’s Howe, written by Howe and the Toronto writer Bob Hesketh, from which young players who have a dollar and two soup carton fronts can learn the fundamentals. Howe also has a column in the Toronto Star.

Howe will likely stay in hockey when his playing days are over. The Red Wings have already named him an assistant coach, and it does not seem impossible that he will take over all the coaching when he retires, so that Sid Abel, now handling both that job and the general manager’s, can concentrate on being manager.

There is some light on the horizon for the fans who will miss Howe’s power and grace. At least one of his three sons — to avoid family jealousies no one is supposed to say publicly which one — has all the makings of a hockey player. He’s big for his age, skates with long, strong strides, and has a powerful shot. But I suppose it would be too much to hope for another Gordie Howe.