The medical lottery: treatment rates vary wildly from one city to another

A look at the highest and lowest rates of surgery in the country

Ghislain & Marie David de Lossy/cultura/Corbis

Share

Ewan Affleck, medical director of Yellowknife’s health and social services, describes it as “a huge issue that is largely unaddressed” in Canadian health care, in many ways “a hidden secret.” He’s seen it in the places he’s worked as a family doctor, from urban clinics in Montreal to hospitals and nursing stations in the Inuit villages of northern Quebec, and now in the primary-care centres of the sprawling Northwest Territories.

The secret is “unwarranted variation”: the stark and sometimes alarming regional differences in the health care patients receive, determined by things like the capacity of the local system on a given day or the preference of the doctor instead of actual need or even medical evidence. Canadians participate in a lottery every time they have a brush with the health care system; it can mean the difference between getting screened for prostate cancer or not, or whether or not you have your uterus removed. Though medicine is now supposed to be evidence-based, the simple fact of where you get care, and from whom, can influence your treatment as much as the latest science.

This arbitrariness disturbed Affleck, who has the lean frame and single-minded focus of the ultra-marathon runner that he is. “This is a national issue,” he says. “Who drives the Canadian health system? The day-to-day drivers are mostly doctors and other health professionals.”

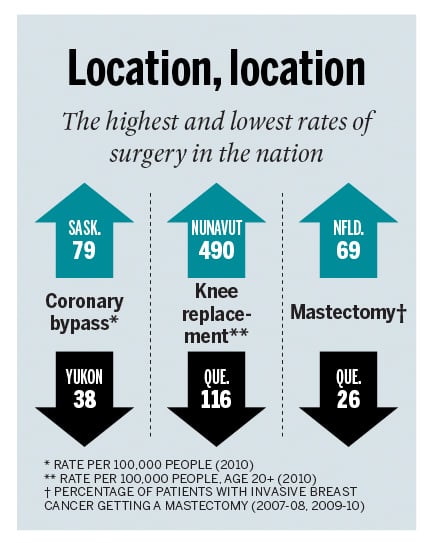

The decisions those doctors and nurses make lead to jaw-dropping variations in care. According to an October report released by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), an independent non-profit, there’s a huge range in the kinds of surgical breast cancer treatments Canadian women receive. A woman is much more likely to undergo a mastectomy (removal of the cancerous breast) instead of a less invasive lumpectomy in Newfoundland and Labrador, where mastectomy rates are 69 per cent, than in Quebec, where they’re 26 per cent. This despite the fact that for decades, the medical community has known that the breast-preserving lumpectomy with radiation can have equivalent health outcomes.

CIHI reported that, in 2010, rates for hysterectomies fluctuated similarly, from 435 per 100,000 women in Saskatchewan to about half that—258—in Nunavut. Such aberrations are not confined to women’s health. The same year, knee-replacement surgeries ranged from 490 per 100,000 people aged 20 and older in Nunavut to a mere 136 in Newfoundland and Labrador. The rate of patients getting heart bypass surgery was 79 per 100,000 in Saskatchewan compared to only 43 per 100,000 in neighbouring Alberta.

“Clearly, when you see a two-fold variation in hysterectomy rates,” says Brian Goldman, an ER doctor in Toronto and a Canadian health-care analyst, “some of them have to be unnecessary.” Goldman points out there can be variations in practice patterns for open versus laparoscopic hysterectomy, or based on drug shortages; there may be a local expert who influences practice. “Patients should care if they are getting an operation they don’t need,” he says.

Those who study regional discrepancies estimate that as much as 20 to 30 per cent of care doctors provide is unnecessary—which can mean pointless

surgeries, wasted days in hospital, squandered resources and, worst of all, avoidable complications and deaths. Yet, as Affleck says, “If what we’re doing may be supply-driven or preference-driven, not necessarily based on effective care, most doctors don’t know that, because we haven’t had the capacity to measure ourselves.”

Until now. Affleck is part of a new generation of front-line health workers using data from their own clinics to identify and minimize haphazardness where care deviates from best practices and, with any luck, to improve patient outcomes along the way.

Gathering data on health care trends and outcomes has traditionally been the domain of public-health officials or epidemiologists, who take a bird’s-eye view, looking at health regions or provinces. The phrase “unwarranted variation” was coined by an epidemiologist, John Wennberg. In sweeping studies of the U.S. system that have been going on for about half a century, Wennberg found a counterintuitive relationship between higher spending in health regions and worse outcomes, concluding that supply—or the availability of medical services—drove usage, instead of science or patient need. In other words, more in medicine is not necessarily better.

In recent years, the profession has tried to address this paradox, in part by determining what works. Hospitals have begun to track and publish indicators like readmission or surgical complication rates. In the U.S., they are even being paid according to how well they hit these targets.

Yet these efforts to measure and reward quality have been far removed from the drivers of the system, as Affleck put it. That’s partly because quality primary care—counselling a grieving patient, comforting the worried well—tends to be less measurable than, say, surgical outcomes. But it’s also because, before electronic medical records (EMR), measurement in clinics was tedious, almost impossible. The lone GP would need to crunch data and look for trends in thousands of patient charts. But with EMRs, Goldman notes, “Now you can do this at the touch of a few buttons.”

In 2005, Affleck helped launch what has evolved into a territorial EMR covering more than half of the 41,000 patients who populate a 1.3 million-sq.-km expanse. It has allowed him to begin to grapple with variations in care that may be occurring in Yellowknife.

About a year and a half ago, he introduced “mentorship rounds.” Every two weeks, doctors and other health professionals gather at the Yellowknife Primary Care Centre. “We take a turn pulling data off the EMR,” says Affleck, “and compare what we’re doing with, for example, screening for prostate cancer, to what international standards or guidelines are.” In looking at the number of PSA prostate screening tests that were ordered, they found they had doubled their requests in the previous year. Why was this? Affleck and his team discussed the question. “Is this driving care that may not be warranted?” he asks.

They also looked at whether they were doing enough to help patients quit smoking, and whether diabetics were being looked after to guideline standards. “When we’re extracting data, we’re looking at outcomes,” says Affleck. If the blood sugar of diabetics in the region is higher than average, doctors can adjust the care they offer—perhaps introduce group teaching sessions—and begin tracking patients’ levels over time. “You can monitor these patients to see if they’re improving or not.”

Though these are early days, Affleck believes that simply reflecting on your practice using data may improve quality, and he’s trying to instill that idea in the next generation of doctors. “Data is not something we’re brought up to embrace,” he says of Canadian family practice. But it can be a useful tool.

In Taber, Alta.—a town just north of the U.S. border—family doctors are using their EMR system as the foundation of a larger plan to reduce unwarranted variation. Rob Wedel, who moved there from Calgary in 1976, is the physician lead at the Taber Clinic, which serves a geriatric population mixed with younger new Canadians. He wanted to know whether screening for colorectal cancer was reaching the over-50 population that guidelines recommend be targeted. So he used his clinic’s EMR to find those patients, and began calling them to get their tests done. He also created an alert that reminded clinic workers to ask eligible patients who came in whether they wanted a colonoscopy. “It became a joke here,” Wedel laughs. “Patients would come in for a sore throat and leave with a booking for a colonoscopy.”

When he began the project in 2000, colorectal-cancer screening was reaching about 10 per cent of eligible patients. “Now, 80 to 90 per cent of people who should get screened are getting it.” A bit of data extracting and feedback reduced the randomness of who got tested, and Taber now meets the national standard.

More startlingly, Wedel improved outcomes for asthmatic patients. Asthma is prevalent in Taber because of agricultural work. Wedel found the asthmatics in his practice on his EMR and designed a program that involved regularly calling them to talk about how to manage their asthma. He calls it “proactive surveillance,” and the result was that visits to the ER for asthma dropped from 450 to 24 per year. “Asthma is no longer even on the top 10 reasons for people to come to emergency anymore.”

Whether these efforts lead to better overall health remain to be seen. But Wedel and Affleck point out that, in a time when questions of health-system sustainability and cuts abound, a little reflection can’t hurt. “Let’s look at what we’re doing,” Affleck says. “In our industry, we understand what quality is, and ultimately the goal is to deliver quality care. So if there’s a uniform understanding of what quality is, how can there be significant variations?”