Why we need to clear our cluttered minds

Recognizing the problem with multitasking, and how to cope with decision fatigue

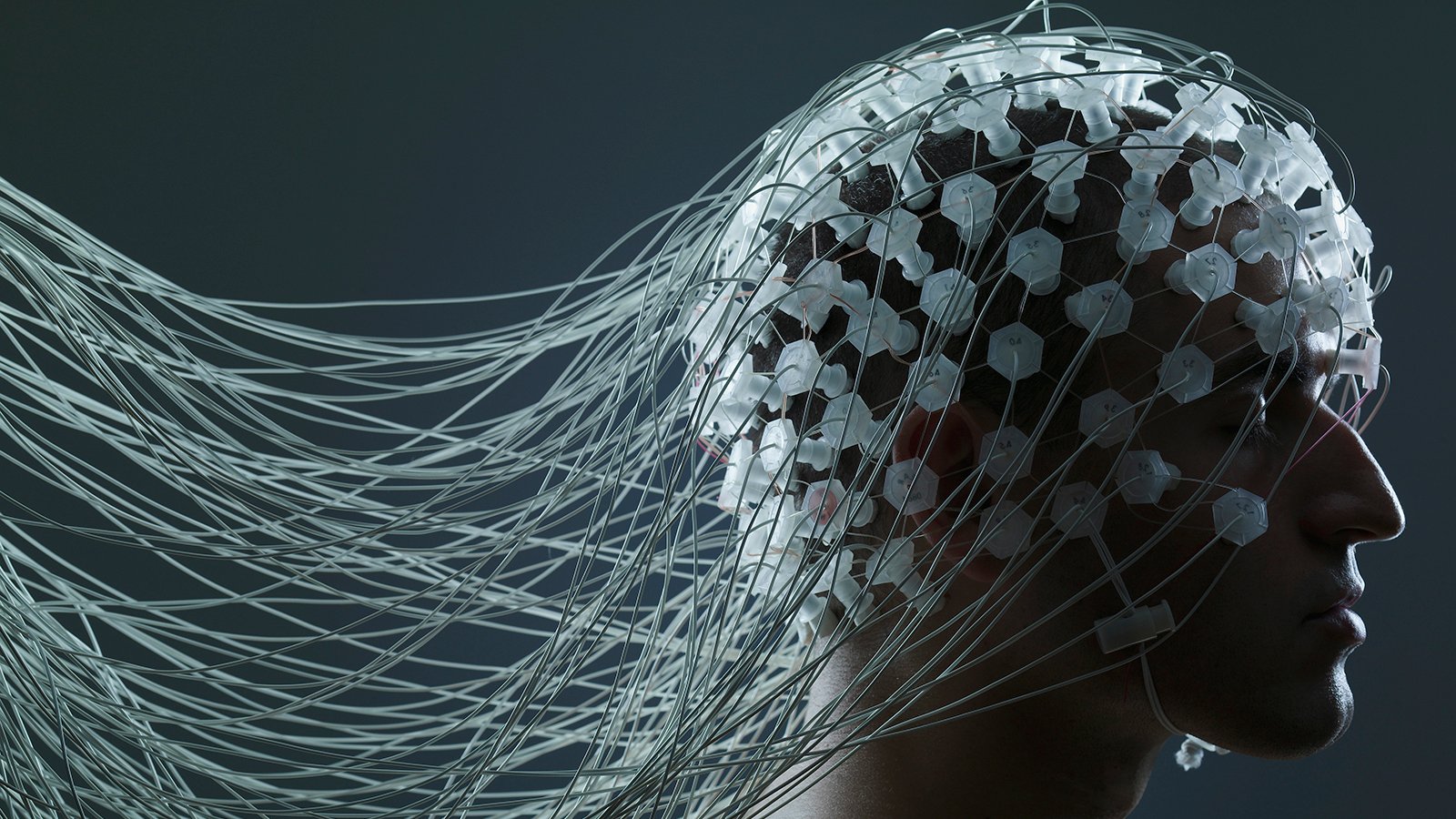

Man with Electrode Wires on Head — Image by © Adrianna Williams/Corbis

Share

Updated Jan. 18, 2018

If the world feels like it’s getting more complicated, that’s because it is—in ways both large and small, and with discombobulating speed. In 1976, the average supermarket stocked 9,000 different items. Today, its shelves are packed with 40,000. The spread of TV, video and computers—at work, at home and in our pockets—means that the average person now takes in the information equivalent of 175 newspapers each and every day, a fivefold increase since 1986. The amount of science produced over the past two decades surpasses all of the theories, experiments and discoveries ever created in the preceding 100,000 years. The flood of knowledge, choice and distractions never slows.

“We are faced with an unprecedented amount of information to remember and objects to keep track of,” writes Daniel J. Levitin in his 2014 book, The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload. Yet, “in this age of iPods and thumb drives, when your smartphone can record video, browse 200 million websites, and tell you how many calories are in that cranberry scone, most of us are still trying to keep track of things using the systems that were put in place in a pre-computerized era.”

Our compulsion to be organized runs deep. It’s a combination of ancient imperatives—Can I eat this mushroom? Where was that watering hole? Is this the cave with the bear?—and desirable modern outcomes, including educational attainment, workplace success, robust health and longevity. But evolution hasn’t kept pace with the information revolution. And Levitin, a musician, record producer and McGill University neuroscientist, is sounding the alarm about the consequences of spreading ourselves and our attention too thinly. “It brings on a real phenomenon called decision fatigue,” he told Maclean’s. “Every decision you make requires resources. Neurons are living cells with metabolisms. When they work, they need to replenish themselves with glucose, and that’s not in unlimited supply in the brain. So, whether you make a tiny decision or a big one, you’re using up those resources. The amount of choice we have in a place like a grocery store can be overwhelming. And, later in the day, when you have to make some important decision at work, or about your pension, you’ve depleted those neural resources selecting a gluten-free cereal.”

Focusing on what really matters is difficult at the best of times. But as our daily lives have become busier, we have paradoxically incorporated all sorts of new distractions, from email to texts to social media, into our routines. Multitasking is addictive, Levitin concedes. “We’re a productive species and we have an evolutionary history that finds pleasure in accomplishing things. So, every text message you send, every email you reply to, every Facebook update you post, makes you feel like you’ve crossed a task off your mental list.” In turn, that triggers the brain’s reward system, which releases dopamine and other neural chemicals that induce feelings of contentment and happiness. “You get this pleasure-reward loop going,” he says. “It’s the same chemicals that are responsible for people becoming addicted to cocaine and heroin.”

What those good feelings mask is the reality that all our busy work doesn’t amount to much. “People think they are multitasking and getting a whole lot of stuff done, but what they’re doing is rapidly switching from one task to another. It’s a cognitive illusion,” says Levitin. All that refocusing eats away at both our time and our energy. “People don’t realize the loss of productivity because they aren’t measuring it.”

(To combat the phenomenon in his own life, Levitin now sets aside a certain period each day to answer emails or tweet. At all other times, he tries to remain unplugged and locked-in on the task at hand.)

There’s also a growing body of evidence that suggests our “smart” devices are, in fact, making us dumber. As search engines and databases have proliferated, we have come to rely on them for the kind of basic facts and figures—phone numbers, loved ones’ birthdays, the year Samuel de Champlain first sailed up the St. Lawrence—that we used to carry around in our brains. (To save you checking, it was 1603.) As our comfort level with such “outsourcing” grows, we seem to retain less and less information. In one well-known 2011 study, a group of Columbia and Harvard scientists asked participants to type bits of trivia into a computer. Half were told the information would be saved on the hard drive, and the other half that it would be erased. Quizzed afterward, those who were convinced they wouldn’t be able to revisit the factoids at the click of a mouse proved significantly better at recalling them. Other studies indicate that we seem to absorb less information off a screen than a printed page. Researchers at Norway’s Stavanger University tested the emotional effect of a disturbing short story consumed on paper versus an iPad, and found that the print readers were drawn in more deeply, and had greater empathy for the characters. In a follow-up experiment with a Kindle, published last month, the same team found that those who read on devices were “significantly” worse at recalling details, characters and settings in a short story than those who were given it in paperback. It may simply have to do with location. After reading a book or magazine, we can more easily visualize where events occurred on a page, and where they fit in relation to other details, allowing us to more easily reconstruct plots or events.

Levitin doesn’t necessarily see that as a problem. One of his keys to coping with information overload is to “externalize” our more mundane memory tasks by making lists or using prompts, such as taking the empty carton with you when you need more milk. But what that electronics-induced inattention does necessitate, he argues, is the creation of a kind of triage system in our daily lives to separate out the things that are really important to remember. “One technique is to be consciously aware, and focus your attention,” says Levitin, and to find a way to associate the task, item or insight you need to keep top of mind with an emotion. “As a rule, the things that have the most impact on you are the things you remember best. If you really care about something, you’ll remember it. So, even if you have to steel yourself and manufacture that caring, it helps,” he says.

The strong link between our memories and our emotions has long been recognized by scientists, especially when it comes to fear: From an evolutionary perspective, we are hard-wired to recall the threats and hazards we encounter in order that we might learn from our mistakes and survive. Happy or sad events are also more likely to be permanently etched in our minds, in particular, those we experience in our formative years. That “reminiscence bump,” as researchers term it, peaks around the age of 20 and explains why a first kiss or teenage breakup might still be vividly recalled even decades later.

Forgetting is also important, however. Brian Levine, a neuropsychologist and senior scientist at the Rotman Research Institute at Toronto’s Baycrest Hospital, notes that most things we encounter or do on an average day aren’t really worth remembering. “If all that information was stored or encoded in the brain, we’d be overwhelmed,” he says. Most people have a fairly decent recall of what has happened in the past 24 hours, but, beyond that, things rapidly begin to fade. “We evolved to think of today and tomorrow, basically,” says Levine. “Contingencies and circumstances change. It doesn’t make biological sense to retain all that information.”

Interestingly, emotion as a memory aid does have its limits. Levine and his colleagues published a study in 2014 of passengers who were aboard a 2001 Air Transat flight that ran out of fuel and nearly had to ditch at sea, before the pilot miraculously glided into a safe landing at an air base in the Azores islands. About half of those who participated in the project had developed post-traumatic stress disorder after their brush with death, and the researchers had anticipated that their memories of what occurred that day would be sharper than those of passengers who had fully recovered from the shock. But the amount of detail both groups were able to recall was essentially the same. What that suggests, says Levine, is that PTSD has more to do with how people process their memories than how they experienced the trauma is the first place.

A 2014 University of Illinois at Chicago study of depressive young adults came to a similar conclusion. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine the brains of both depressed and healthy 18- to 23-year-olds, scientists found that those with a history of mental illness seemed to be “hyper-connected,” with significantly more cross-flow between the emotional and cognitive networks of the brain. The heightened activity indicates that those with a history of depression spend more time ruminating on their emotions, wrote the researchers, a “not very healthy way” of working through problems.

Of course, there is also an emotional component to our need to be organized. In his book, Levitin references a survey that says three-quarters of Americans report that their garages are too stuffed with junk to fit a car, and another inventory of a typical household that counted 2,260 visible objects in just the living room and two bedrooms. All that clutter creates stress—particularly in women, he says—and the release of the hormone cortisol, which, in turn, can lead to cognitive impairment, fatigue and even a suppressed immune system.

Clare Kumar, a professional organizer who runs her own productivity consultancy in Toronto, says her clients are often in severe distress when they reach out for help. “Their environment is screaming at them,” she says. “They feel stifled.” But after a thorough decluttering, and being taught some basic strategies to put their lives and homes in order, most find that their productivity and happiness suddenly spike. “It has to do with breathing and space and being able to function,” says Kumar.

Levitin is a strong believer in creating systems at home and at the office, sorting items into labelled drawers, plotting out detailed work and social calendars, and organizing our digital desktops. Yet he also preaches the virtues of balancing it all with unstructured time, including periods dedicated to daydreaming, when we are free to think nonlinearly, innovate and problem-solve.

The biggest challenge facing our disorganized, overrun society, he says, is teaching our children how to deal with the wired world we have bequeathed them. “There’s been a dramatic shift in the last 20 years. We used to train people to acquire information; so much of school was about cramming your head full of facts and telling you where to find more of them if you ever needed to follow up. Now, everybody has instantaneous access to any fact they want,” says the author, “but we haven’t been teaching people how to use those facts creatively and intelligently. I think that’s how education needs to change at every level, so that from a young age, children are taught how to be critical thinkers.”

The dangers of continuing down our current path are more than apparent. A 2014 student survey out of Baylor University in Texas that found that female undergraduates now spend an average of 10 hours a day interacting with their phones, and males eight hours. All the texting, surfing, online banking and listening to music isn’t leaving much space for anything else, the school warned.

It’s high time to start getting organized.

Update