How facial recognition software is slowly eroding privacy

Our editorial: New face-tracking technology offers an invaluable tool for law enforcement, but as it spreads there will be a strong temptation to misuse it

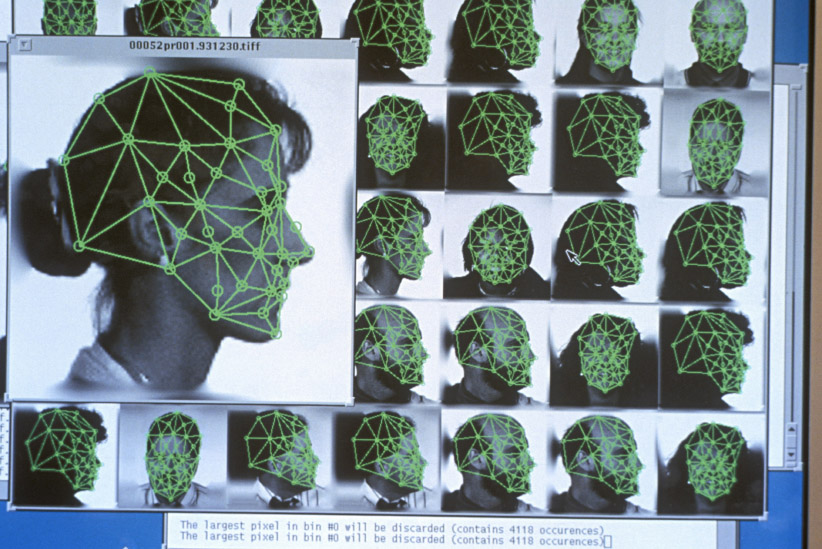

Digitized facial recognition using grid with specific female points. (Stegerphoto/Getty Images)

Share

“Run it through facial recognition.”

For fans of television crime and spy dramas, it’s a familiar phrase. A face caught on a security camera or ATM is “run through” the system. A hundred faces flash per second until a match is procured. And before the next commercial break a SWAT team is breaching the miscreant’s front door—justice served, thanks to the latest crime-fighting technology.

As satisfying as this can be for television viewers, however, the rapid proliferation of facial recognition in our everyday lives is also deeply unsettling. While facial recognition may offer new ways to catch terrorists, it also threatens the inherent right of citizens to be left alone from constant government supervision. Canadians should be paying close attention to current experience in the United States as a grim warning of what may lie ahead if we’re not vigilant in protecting our own privacy rights.

READ MORE: So, when do we start caring about privacy?

Congressional hearings last month unearthed shocking evidence of the FBI’s use of facial recognition under its Next Generation Identification program. In addition to its own collection of 30 million mug shots, the FBI now admits to making deals with states allowing it access to driver’s licence photos and other sources of identification. In total, the FBI can scan over 411 million facial pictures. Excluding double entries, nearly half of all American adults can now be “run through” facial recognition.

Even more disturbing, the FBI was operating without appropriate supervision, as mandatory privacy-impact assessments were years overdue. The ability to collect and recognize faces was essentially hidden from the public and government. Congress also heard the technology may be quite a bit more fallible than often assumed, with a failure rate of 14 per cent. A disproportionate share of these misidentifications involve black Americans.

Whatever its effectiveness, the technology appears to be spreading rapidly. The plan to replace existing toll booths at New York City’s bridges and tunnels currently involves a camera-based system that will scan drivers’ faces as well as their licence plates. If this goes ahead, the state will be able to track its citizens as they go about their daily routines, in real time. It’s a significant and worrisome step toward an all-encompassing surveillance state.

In Canada, the state of the technology—and the threat it poses to individual freedoms—is not quite so dire. But it is certainly becoming more commonplace. Recently, facial recognition kiosks were unveiled for the first time at the Ottawa International Airport. These devices, soon to appear at other busy airports, verify the identity of travellers by comparing their faces with the pictures on their passports. Municipal police services across the country have also been using the technology for several years to access their repository of mug shots. Nationally, however, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada says it has not been formally consulted or received any privacy-impact assessments from the RCMP on the technology. (Then again, federal agencies such as CSIS and the Communications Security Establishment are not answerable to the federal privacy commission.)

We can be thankful that Canadian privacy laws are considerably more robust than in the U.S. “Our laws are very strong and have independent oversight,” says Ann Cavoukian, a three-term privacy commissioner for Ontario now working in academia. Privacy rules also forbid the use of collected information for purposes other than originally intended—meaning driver’s licences and toll booth photos should stay off-limits to Canadian police. Nevertheless, American experience reveals the great and constant temptation to use whatever new technology might offer an edge.

The right to privacy, like the security of the nation, requires constant defence.