The Internet vs. Hamza Kashgari

How an online lynch mob left a Saudi writer facing a death sentence

Share

From the green-clad tide of pro-democracy demonstrators who took to the streets of Tehran in 2009 to the ongoing demonstrations in Egypt, we’ve been led to believe that social media can be a force for good. Young people inciting others to action against repressive regimes through Twitter; witnesses putting videos on YouTube decrying state-sponsored violence; Facebook groups inviting protesters to gather at a square to chant for freedom. Yet in the case of Hamza Kashgari, a 23-year-old newspaper columnist from Saudi Arabia, the Internet has emerged as the source of repression.

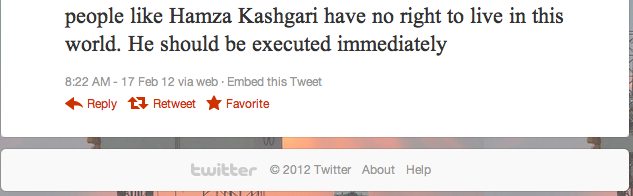

Saudi Arabian authorities have charged Kashgari with blasphemy, apostasy and atheism for a series of tweets about the Islamic prophet Muhammad he posted on Feb. 4. On the prophet’s birthday, Kashgari wrote: “I love many things about you and hate others, and there are many things about you I don’t understand” / “On your birthday, I shall not bow to you” / “I shall not kiss your hand. Rather, I shall shake it as equals do, and smile at you as you smile at me. I shall speak to you as a friend, no more.” (Translations from the WashingtonPost and the Christian Science Monitor.) Minutes after the posts went live, hundreds of angry tweeters were using a hashtag translated as “Hamza Kashgari the dog” urging authorities to punish him. (A hashtag is the “#” symbol used to identify topics on Twitter; dogs are considered unclean animals by many Muslims, so calling someone a “dog” is particularly offensive.)

Kashgari deleted his messages and apologized that same day, but by then he had offended many people. The Internet lynch mob extended to Facebook, where a group called “The Saudi people want the execution of Hamza Kashgari” reportedly gathered over 20,000 fans in just two days. Sheikh Nasir al-Omar, an Islamic activist who posts a daily video lesson on YouTube, wept dramatically as he called for Kashgari’s execution for blasphemy in his Feb. 5 appearance: “I plead to the King and Prince, God bless them, that these people are taken to the Islamic courts for punishment,” he says. (Watch the subtitled video here.)

Having seemingly learned from Egyptian and Iranian states to keep an eye on social media, Saudi authorities took note of the online outrage against Kashgari and raced to capitalize on it. The columnist was apprehended in Malaysia, where he had stopped on his way to New Zealand to escape, and sent back to his native Saudi Arabia. Kashgari is now in jail. According to Waleed Abu Alkhair, a human rights lawyer who has been tweeting about the case, he is being kept in solitary confinement and has been denied access to a lawyer. Earlier this week, Kashgari was denied a trial before the Information Ministry, meaning he will have to appear before a religious court instead. Apostasy, one of the charges laid against him, is punishable by death.

Ironically, Kashgari’s best hope for survival may be with a support campaign that has gone viral on the Internet. His case has become the latest cause célèbre online, with thousands of people calling for his release on different social media outlets. The Facebook page called “Save Hamza Kashgari” counts 8,000 followers. Major human rights organizations have taken up the case, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Friends of the columnist have created the page freehamza.com, where over 22,000 people have signed a petition calling for his release; at least two other pro-Kashgari petitions are also circulating the Web. Several famous human rights activists with large Twitter followings, including Cuba’s Yoani Sánchez (over 200,000 followers) and Arabic journalist Dima Khatib (over 87,000 followers) are mobilizing support for Kashgari.

His case has already crossed over into the political arena. On Feb. 20, Sheikh Ali Gomaa, Grand Mufti of Egypt and a respected Islamic jurist, told an English-language newspaper he disagrees with Kashgari’s treatment. “[In Egypt,] we don’t kill our sons, we talk to them,” he said. Hussein Ibish, one of the most respected secular Arab scholars and a Senior Research Fellow at the Washington-based American Task Force on Palestine, wrote on Feb. 21 he believes Kashgari won’t be executed thanks to the mounting public pressure on Saudi authorities. However, Kashgari could still face years in prison—by all means a disproportionate punishment for his actions.

The online mob that prompted Kashgari’s downfall calls into question the notion that social media is an inherently positive force. In this disturbing case, it was the righteous and the blood-hungry who mobilized first. Dr. Anatoliy Gruzd, Director of the Social Media Lab at Dalhousie University, says that, “as a tool, social media can be used for good or for evil.” However, Gruzd says the evidence shows social media is “more likely to be used as a source for good, because it tends to democratize societies.”

It could be weeks, or months, before Kashgari’s case is settled. But in the meantime, his case has sent a chill among social media users in countries where repressive governments are learning how to use the tools for their own, twisted benefit.