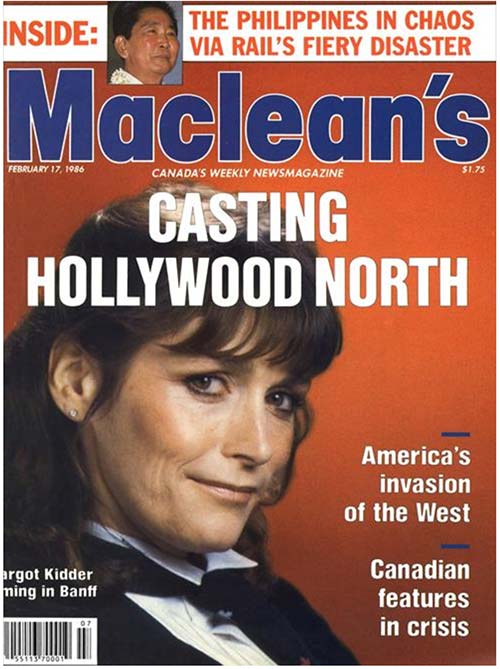

Margot Kidder: A Canadian star returns

From February 1986: Kidder is one of the most prominent Canadian actors who have found fame and glory in the U.S., yet are returning home to participate in Canada’s burst of film-making

Share

This story originally appeared in the February 17, 1986 issue of Maclean’s under the headline “A Canadian star returns”

With little more than $500 in her pocket and what she now calls “a strangely self-confident but ignorant ambition” to become a movie star, Margot Kidder left Canada 18 years ago for the bright lights of Hollywood. She knew that she would succeed. After all, while living in Labrador when she was 9, Kidder had written in her diary: “I want to be a popular actress—sort of like Annette [Funicello].” And as a teenager in Vancouver she retired to her bedroom daily to practise crying. With her exquisite bone structure, husky voice and sardonic edge, she did conquer Hollywood. By 1979 her appearance as the comicbook heroine Lois Lane in the year’s box-office smash, Superman, helped her soar to stardom. Her career has spanned 27 feature films, several television movies and the 1971 TV series Nichols, with James Garner, making her, at 37, one of Canada’s most bankable leading ladies in Hollywood. Declared Richard Donner, who directed her in Superman and Superman IT. “When Margot acts, she comes right off the screen and into your life. She’s an actress who should be right up on top.”

Glory: Kidder is one of the most prominent Canadian actors who have found fame and glory in the United States and yet are returning home to participate in Canada’s current burst of film-making. Last week in Banff she completed shooting the $2.5-million CBS television movie Hoax, a police drama set in a mythical American Rockies town, co-starring Elliott Gould. It was the second U.S. made-for-TV movie she shot in Canada in the past year, the other being Picking Up the Pieces, also for CBS. At the same time, domestic producers looking to fill Canadian content quotas clamor to have Kidder in the credits. Two months ago she completed shooting Keeping Track, a Canadian feature thriller shot in Montreal. Few actors have benefited more from Canada’s two concurrent film booms (page 34) than Kidder, who holds the requisite cultural credentials: a Canadian passport and a home in Malibu. “I get offered everything,” she said, “no matter how inappropriate.”

Despite the current burst of activity in her career, Kidder has reached a turning point in her life. Faced with the lack of serious film roles for women in Hollywood and the volatile state of Canadian feature film-making, she has been forced to turn more and more to television movies. She is preparing to leave Malibu, where she lives with her 10-year-old daughter, Maggie, and relocate in Montreal.

And being the object of the camera’s gaze for 20 years, she plans to move to the other side and direct. She has served as an apprentice editor for acclaimed U.S. director Robert Altman and has directed a short film at the respected American Film Institute in Washington, D.C. Said Kidder: “The Canadian film industry is a flower in bud. It can turn either into a dandelion or a rose. But if it goes anywhere, I want to be a part of it.”

Passion: Kidder’s plans often seem quixotic. Impulsive by nature, she has acquired a reputation for activist politics and a flamboyant private life—three times divorced, she has recently been seen with former prime minister Pierre Trudeau. But she says that she has never felt at home in Hollywood. More intellectual than most stars, she is a fascinating amalgam of passion and vulnerability with a taste for adventure. Said Donner: “Margot is like four-wall handball—you never know where she’s coming from.” Frank Mankiewicz, former press secretary of President John F. Kennedy and now a Washington lobbyist, first met Kidder on a plane in 1984. His cousin Tom Mankiewicz was the creative director for Supermam, discovering that they had mutual friends, Frank Mankiewicz and Kidder struck up a conversation. Recalled Mankiewicz: “She got off the plane in San José thinking she had arrived in San Francisco. So she took a cab the rest of the way.”

Dangers: She has always beaten her own path around California, struggling against the dangers of typecasting. Often used in the roles of offbeat but spirited sex objects, she has actively sought other jobs. She has played everything from murderous Siamese twins, in Brian De Palma’s Sisters, to a fearful wife in The Amityville Horror. In 1981 she g accepted the role of a prostitute in Some Kind of Hero without having read the £ script, just so that she could work with its star, Richard Pryor. And when she was dissatisfied with the quality of scripts offered to her after Superman, she formed her own production company and cast herself as Eliza Doolittle in a made-for-TV version of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Said Stuart Margolin, who directed her in the 1983 murder movie Glitter Dome: “Margot’s own pride kept her from doing the same things over and over again. She’s got more to think about than being Lois Lane and making grins.”

Her consistent desire to stretch the limits of her talents has earned her a reputation for being difficult to work with—demanding rather than merely temperamental. Said Jamie Brown, her co-producer and writer on Keeping Track: “She is a person who says what she thinks. If she thinks something is crap, she says it’s crap.” Indeed, Brown recalled that during the production of his drama, Kidder told him: “Don’t worry, Jamie, we fixed up your script.”

Magnetic: Kidder is a naturally magnetic actress. In her early 20s she went to New York for classical training but recalls that her coach told her: “You know exactly what to do, but you don’t know what you are doing and if I tell you I’ll ruin you.” Added Superman director Donner: “I’ve always said to Margot, the minute you start analysing your performance, you’ll blow your career.” Because acting comes so easily to her, she tends to denigrate her abilities. In 1980, after auditioning and winning a part in director Paul Mazursky’s Willie and Phil, Kidder sent Mazursky a revealing telegram. “I’ve just got a job as an actress in a movie with my favorite director,” it read in a classic display of Kidder’s vulnerability and self-deprecation. “What he doesn’t know is that I don’t know anything about acting. Should I tell him?” Although Willie and Phil failed at the box office, Mazursky had a profound effect on Kidder, giving her the sense that she was wasting her talent and should assume more moral responsibility for her art. “After Mazursky, there was a spirit that I’m going to be a serious actress now,” she said. “I thought, I’m going to break away from this.” Still, says Donner, Kidder has not ruthlessly pursued that goal. Often she has been guided more by personal loyalty than ambition. Said Donner: “Margot gets emotionally involved in things. If someone comes to her because they need money or because they need her to be in their picture, she’ll do it.”

Those priorities are even stronger when her immediate family is involved . In 1981 Kidder’s younger sister, Toronto actress Annie Kidder, had just had major abdominal surgery when Kidder called her from Los Angeles. After a short conversation Annie fell back to sleep, and when she woke up Kidder was standing at her bedside. Said Annie: “She got off the phone, picked up Maggie and got on a plane. She stayed a month, painted my apartment and bought me furniture.”

That generosity also extends to strangers—especially Canadians. Last week, after shooting ended in Banff, Kidder went to see a performance by K.D. Lang, Edmonton’s country punk sensation. Kidder was dazzled by the female singer’s talent and immediately started thinking of ways to get her some exposure in the United States. Then she formed a strategy. For months the Late

Night with David Letterman TV show had been asking Kidder to make an appearance—“I’m known as cute, candid Kidder on the talk-show circuit,” she said. Kidder, who had been turning Letterman’s producers down, said she now plans to accept—as long as she can bring Lang along with her.

Storm: Those who know her well say that Kidder nearly always honors her commitments to other people’s undertakings. But with some of her own projects, Kidder launches them in a storm of enthusiasm that does not always guarantee a successful conclusion. In 1979, fresh from her success in Superman, Kidder bought an option on the screen rights for Margaret Atwood’s novel Lady Oracle, intending to produce it. She asked Atwood to write the film script, but then Kidder decided to rewrite it herself. Said Atwood: “Margot wanted to produce, write, direct and star in it. Do you know anyone who wants to produce, write, direct and star in a movie?” The project eventually collapsed.

Kidder’s interest in Atwood’s novel reflects a penchant for reading widely. She is a passionate student of politics and she is as conversant with the novels of Aldous Huxley and Fyodor Dostoyevsky as she is with the world of Jane Fonda and Steven Spielberg. She is even a sometime writer. In 1974 Playboy magazine asked Kidder to pose seminude. She agreed on the condition that she write the accompanying text. Said Kidder, “I just wrote what it was like to be in Playboy, what a sham it was, how they airbrushed all the bimbos. It was a real put-down, but they printed it. They won in the end—nobody read the article.”

Freeze: For the past six years she has campaigned actively in support of the nuclear freeze movement in the United States. She has also helped raise funds for Democratic Senator Paul Simon of Illinois, and she even covered the 1984 Democratic national convention in San Francisco for Vogue magazine. It was in San Francisco that she renewed her acquaintance with Mankiewicz, who said: “Margot keeps learning, which is rare in an adult. Most people bank their intellectual capital in their 20s and live off it the rest of their lives. Not her.”

Remote: Kidder began storing her capital in her childhood. Born in Yellowknife, N.W.T., she is the second-eldest in a family of three brothers and two sisters. Following the itinerant career of their mining engineer father, Kendall, the Kidders lived in nine different cities and towns from Labrador to British Columbia. In their more remote postings the family had no TV, so they turned to books. At 13 Kidder was reading Leonard Cohen, with whom she says she conducted an imaginary affair.

Then, in 1962, while the Kidders were still living in Labrador, Kidder went to the exclusive Havergal College private school in Toronto on a scholarship. There, she did her first acting, in a bit part in Peter Pan. Said sister Annie: “Margot was always dramatic, explosive. And she could draw people into that type of energy.” Kidder finished high school in Vancouver, studied drama for one year at the University of British Columbia and then moved to Toronto where she appeared in CBC dramas. She also acccepted a part in a National Film Board movie made by director Peter Pearson, now the executive director of Telefilm Canada, called The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar. Her performance as the eldest daughter of a bush worker in the Ottawa Valley won her wide publicity; indeed, after seeing a photo of Kidder in Maclean’s, director Norman Jewison cast her as a teenage prostitute in Gaily, Gaily, her first Hollywood feature. The 1969 film turned out to be a $10-million disaster—but it launched her American career. By 1975 she was playing the romantic lead opposite Robert Redford in The Great Waldo Pepper.

Turbulent: Meanwhile, her personal life was growing turbulent in classic Hollywood fashion. In the fall of 1974 she began working on 92 in the Shade, based on the novel by Tom McGuane, who was also her director. By the production’s end McGuane had left his wife, and Kidder moved to the writer’s 300acre Montana ranch. In 1975 she had her only child, Maggie. The plan was that Kidder would give up Hollywood to play the real-life roles of wife and mother. But in 1977, restless and depressed, she called an agent in Los Angeles and won her part in Superman.

After Kidder and McGuane split, her subsequent marriage to actor John Heard lasted only six weeks. Then, after shooting Louisiana, a mini-series for French, Canadian and U.S. TV, she married its French director, Philippe de Broca, whom she is now in the process of divorcing. Declared Kidder: “Say I’m good at getting married, but not staying married.” Since 1983 she has sometimes dated Trudeau, but Kidder is reluctant to discuss their relationship. She says only, “I love him very much and he’ll always be very special to me.”

Meanwhile, acting has steadly lost its allure. She had a crisis of sorts two years ago, while shooting a movie called Little Treasure in Cuernavaca, Mexico, with Burt Lancaster. While filming the major confrontation scene at the end of long day of shooting, tempers flared suddenly, says Kidder, and an enraged Lancaster irrationally began “beating me up.” As a result, Kidder spent a week in hospital, sued Lancaster and won an out-of-court settlement.

Kidder now insists that directing films will give her an opportunity to gain more control of her life and to make films that she cares about. She says that the project she wants to start before all others is a film about her family growing up in Labrador. Kidder has written two-thirds of the script and is now searching for a producer to put the financing in place. She says that she is relieved to be moving away from Hollywood. “I can’t think of anything more horrific than becoming an old actress in California,” she said. “Having six facelifts and putting on 18 lb. of blush and tottering around the beach in short pants at 60 is just not attractive.” For Kidder, the sentimental journey home is also a creative step.

— JANE O’HARA in Banff with DAVID SHERMAN in Montreal and ANN WALMSLEY in Toronto