A Voyage to the North

A new exhibit chronicles daily Indigenous life in northern Ontario in the ’50s and ’60s

Share

April 12, 2024

John Macfie grew up in the 1920s and ’30s on a family farm in Dunchurch, Ontario, with his father, a schoolteacher mother who owned a camera, and six siblings. He later flew planes for the Royal Canadian Air Force and, after the Second World War, returned home to plot weather maps and log trees with his father. Eventually, he met an employee from the province’s Department of Lands and Forests, now known as the Ministry of Natural Resources, who scaled their logs. He was interested in the work and, in 1949, joined the ministry, scaling logs in the winter and fighting forest fires in the summer.

The next year, Macfie became a trap management officer and moved to Sioux Lookout, a small town and key administrative hub for remote northern Ontario communities. For a decade, he visited traplines along the Hudson Bay watershed, a sprawling network of rivers and lakes rich with trapping grounds. He monitored fur-bearing animals like beavers, mediated disputes between trappers and reported on issues with animal populations to the ministry. Along the way, he met and befriended people in Anishinaabe, Cree and Anisininew (formerly known as Oji-Cree) communities.

Macfie photographed his travels and wrote about the people he met for Sylva, an in-house ministry magazine. One of his closest friends was a trapper and Hudson’s Bay Company contractor named Philip Mathew, who served as guide and camping buddy. Mathew once walked 300 kilometres from Fort Severn to York Factory just to play his fiddle at a dance. “I can’t vouch for that story but it’s quite possibly true,” wrote Macfie in one of his articles. His relationship with trappers in the area provided poignant insights into the daily lives of First Nations people. He travelled west to Pelican Lake where he met residential school students, north to Fort Severn to photograph locals making clothes, and south to Mattagami First Nation, where he witnessed a knowledge keeper call for moose during hunting season.

In 1960, Macfie moved south to Gogama, Ontario, and, more than 20 years later, retired as a fish and wildlife supervisor. Post-retirement, he kept busy, writing 13 books and more than a thousand newspaper and magazine articles. He also donated around 1,400 of his photographs to the Archives of Ontario.

Paul Seesequasis, a Saskatoon-based Willow Cree journalist and founder of the Indigenous Archival Photo Project, was working on his archival photography book, Blanket Toss Under Midnight Sun, when he came across Macfie’s work. Struck by the candid images, he tracked Macfie down through Facebook in 2016. “There he was, in his nineties but still active, sharp as nails,” says Seesequasis. (Macfie died in 2018, at 93 years old.)

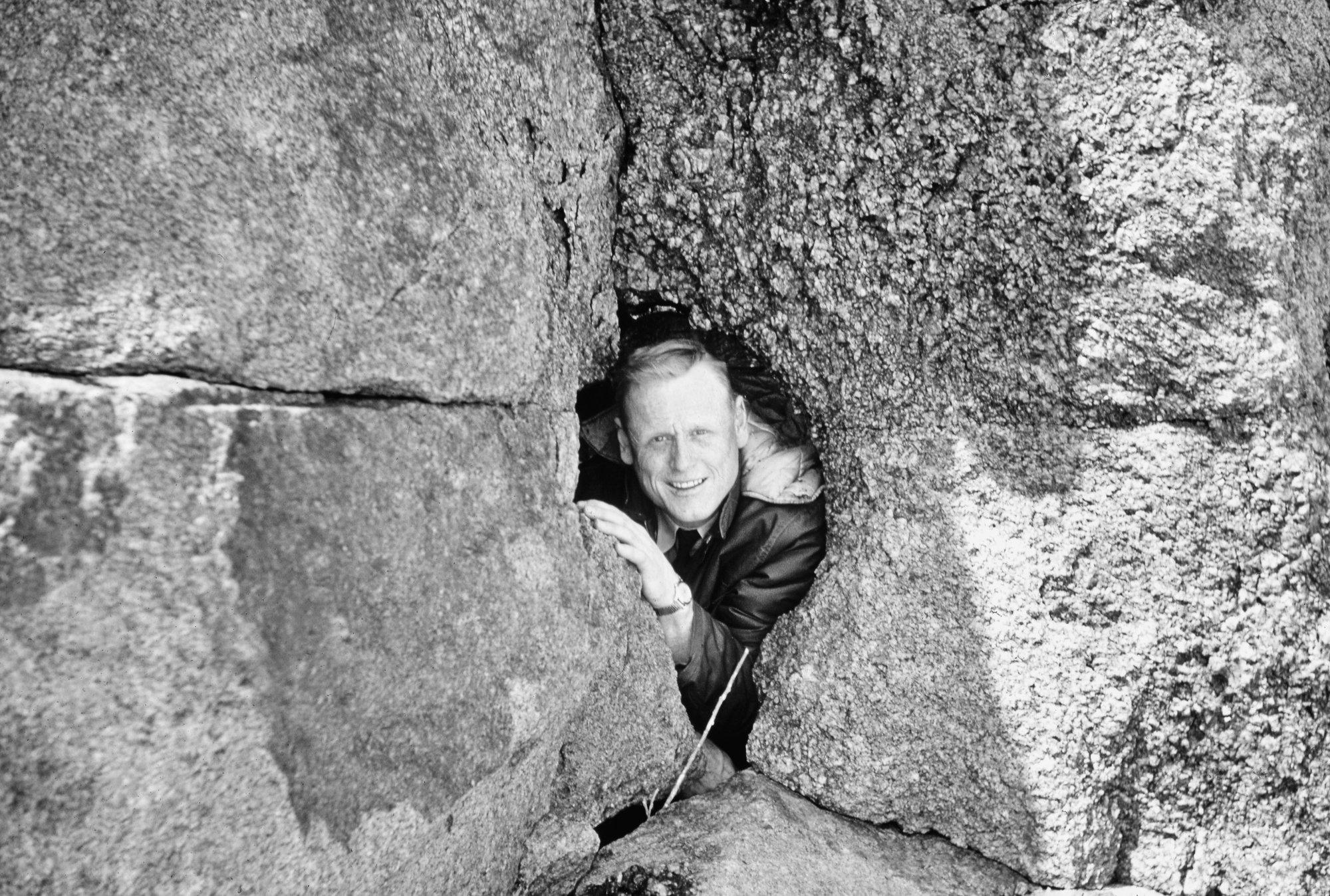

Seesequasis selected over 100 of Macfie’s watershed photos for an exhibit called People of the Watershed: Photographs by John Macfie, on display at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection from May 11 to November 17. Here, Seesequasis tells us the stories behind some of the exhibit’s most revelatory images. “Macfie’s photos are special because he went on week-long trips into bush country as part of his job,” he says. “He was out there living on the land with locals, not a photographer just flying in and out.”

Miss Gray, daughter of Duncan Gray, Fort Severn (1955): “Locals didn’t buy dresses at the time, so women made all their clothes. Each community dressed differently depending on fabrics available at the Hudson’s Bay store. Scottish plaid cloth was immensely popular, but the dress here isn’t plaid, so the Hudson’s Bay store near them must have had a different fabric that day.”

Students at Pelican Lake Indian Residential School, Sioux Lookout (1953): “John rarely visited residential schools because it wasn’t part of his job at Natural Resources. But here he saw these Native boys, students at Pelican Lake Indian Residential School, watching a man fish.”

Philip Mathew, Hudson’s Bay Company clerk (1953): “Philip Mathew was an all-around Indigenous bushman: a guide, hunter and trapper all rolled into one. He was a Hudson’s Bay Company contractor; locals who knew English and the land had opportunities to work for the company because it relied on those skills. Here, Philip is putting resin or pine tar in the cracks of a boat as a safety measure.”

Seal blubber hanging to dry in Attawapiskat (1963): “The Cree in this area hung seal blubber and flesh to feed their dogs. Historically, they were hostile with the Inuit, raiding each other’s camps.”

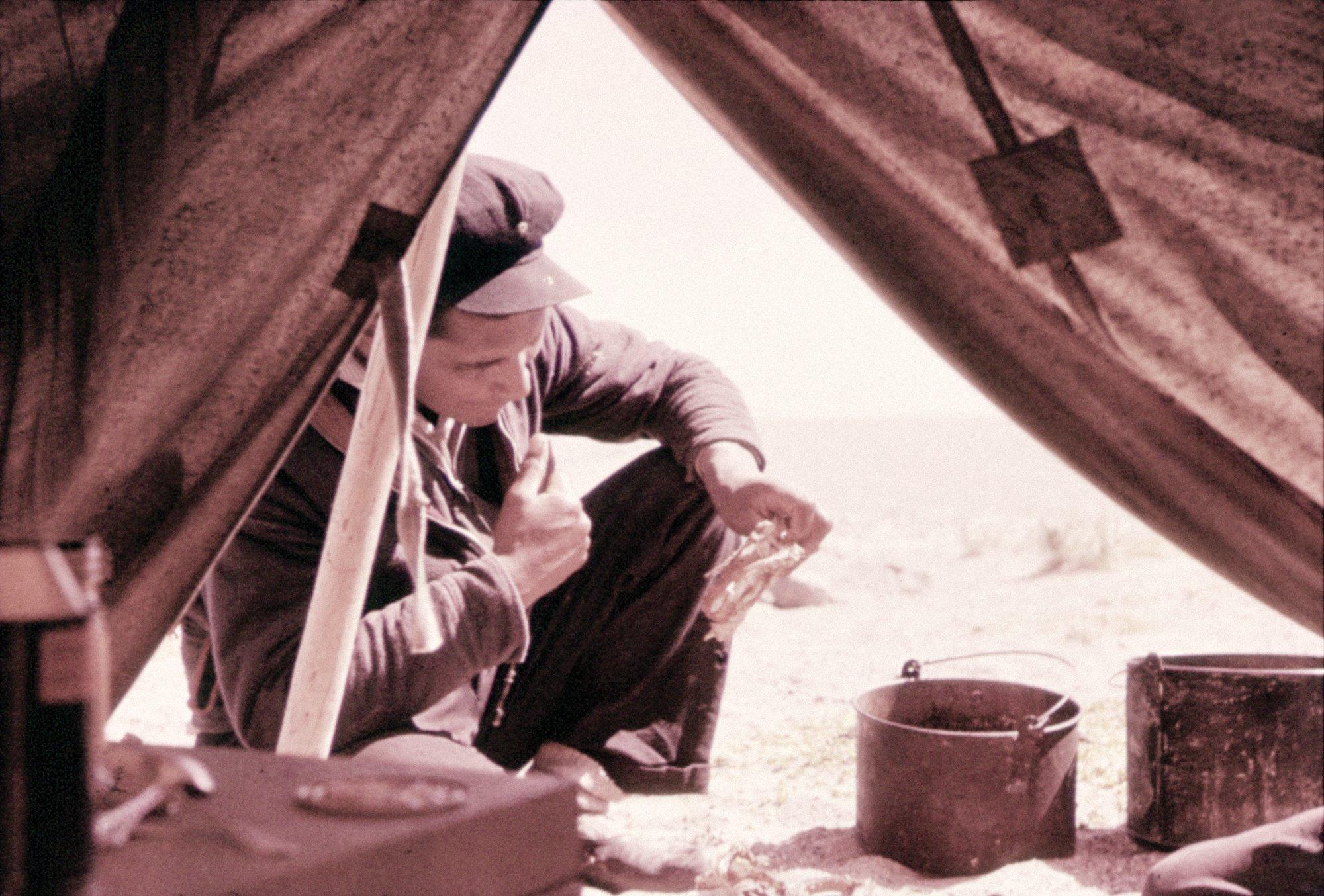

Philip Mathew eating from the broiled carcass of a duck, Hudson Bay Coast (1955): “Philip guided and travelled with John Macfie through many parts of the watershed. Here, they’re camping together.”

Henry Kechebra calling a moose, Mattagami Reserve (1959): “Henry was a knowledge keeper who hunted, trapped and made snowshoes. Here, he’s showing John how to use a moose caller. Made of birch bark, it lures male moose during mating season: Henry would blow into it and produce a territorial call a male moose would make. Hunters would then surprise the moose and kill it.”

Girls skipping rope, Sandy Lake (1955): “Residential schools usually shut down in the summer, so these children had been let out for a break and sent home when this photo was taken. They’re skipping rope, a game that may have predated contact with settlers.”

Child in a tikinagun, Lansdowne House (1956): “A tikinagan, or cradleboard that babies are strapped on to for travelling, was standard in this region. In the distance is Lansdowne House, which was an important gathering space at treaty time. During the event, Indigenous peoples would collect their roughly $4 treaty annuity payment from RCMP officers.”

Webequoi girl standing in front of a teepee at Lansdowne House (1956): “This is not a teepee where people lived, but where they smoked meat—you can tell because the flaps at the tops are closed. Locals there did not traditionally live in teepees but in Ojibwe wigwams, which are small round houses made of wood, bark and grass. By the ’50s, people were living in cabins and houses.”

This story appears in the May issue of Maclean’s. You can buy the issue here or subscribe to the magazine here.