Artist Judy Chicago brings the smoke to Toronto Biennial of Art

Acclaimed artist Judy Chicago is presenting her famous “smoke sculptures” north of the border for the first time

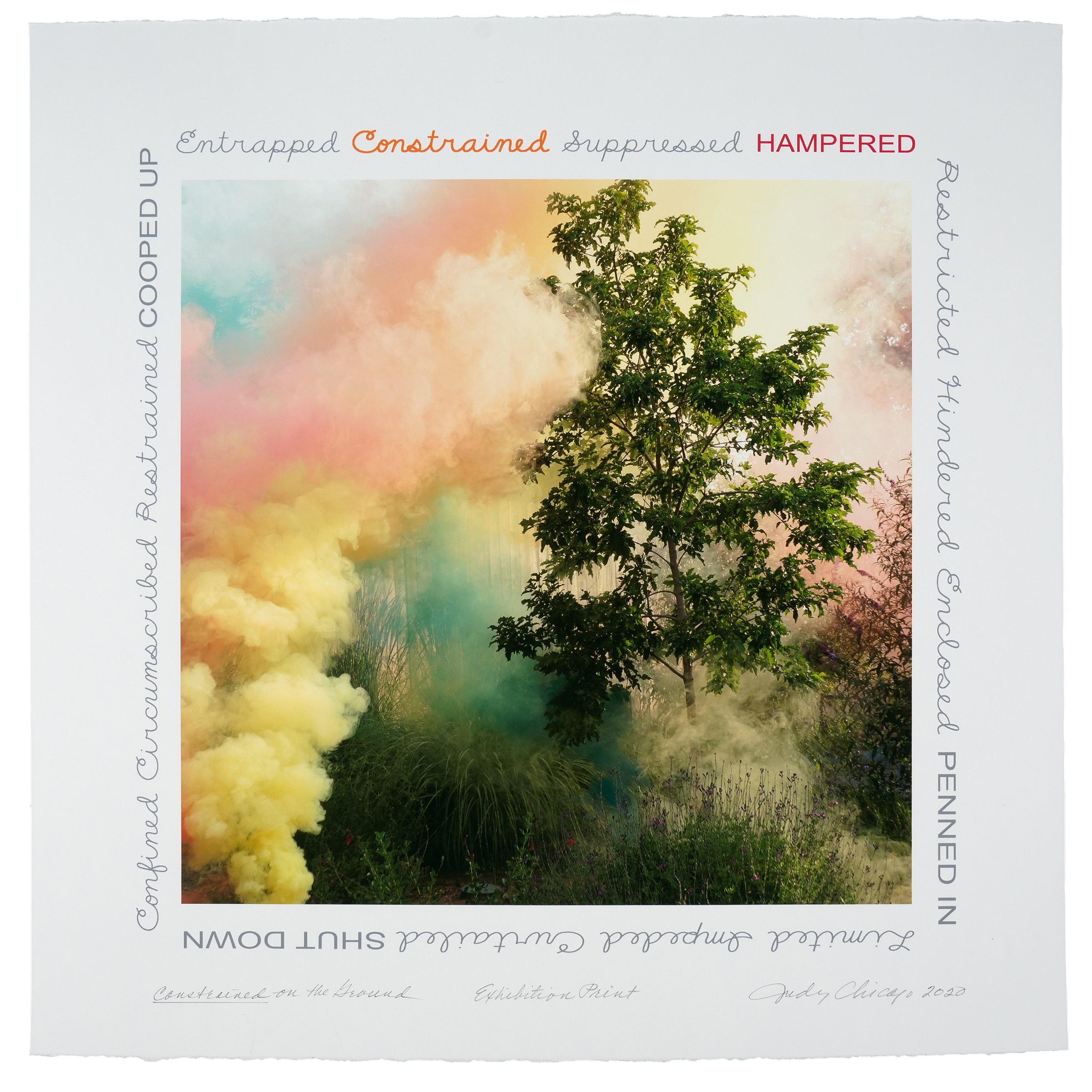

“Control isn’t what I’m interested in,” says Chicago. “Transformation is a better word.” (Photo: Donald Woodman)

Share

On Saturday June 4th, Toronto’s Sugar Beach is going up in smoke.

As part of Canada’s leading contemporary visual arts event, the Toronto Biennial of Art, acclaimed artist Judy Chicago is presenting her famous “smoke sculptures” north of the border for the first time.

Widely known for her multimedia installation The Dinner Party—a triangular banquet set for 39 places, each representing an important woman from history—New Mexico–based Chicago, who’s 82, works widely across genres, from paint to pyrotechnics. Her works are part of major collections across the globe including the British Museum, Stockholm’s Moderna Museet and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Canadian fans can enjoy a double-dose of Chicago’s work this summer. As part of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, works of Chicago’s dating back to the 1970s are on display in a retrospective called The Natural World at Toronto’s Daniel Faria Gallery until July 9.

Her work often plays with themes of environment and continues to be relevant and topical amidst the climate crisis. Though Chicago’s smoke sculptures are ephemeral, she’s sure to leave an imprint that will last long after the smoke clears.

In this interview with Maclean’s, Chicago discusses her new exhibit, the inspiration behind her works and the intricacies of bringing the smoke to Toronto’s waterfront.

***

Your smoke sculptures date back to the late 1960s. What inspired you to work with pyrotechnics?

In 1968, I collaborated with a group of artists to present a street environment in Pasadena, California, where I was living at the time. Thousands of people flocked to the city and set up camp on the streets for the Rose Bowl Parade on New Year’s Day. We thought it would be fun to do something on New Year’s Eve.

My contribution involved fogging the street with fog machines and creating two huge colour wheels over the large klieg lights positioned on either end. The fog rose and the colour wheels turned, causing the fog to become multi-coloured. I found this mesmerizing.

I was already spending a considerable amount of time developing colour systems with the idea of colour conveying emotive states. However, the colour in my paintings and sculptures was contained in a minimalist format. After the street environment, I wanted to work more with coloured smokes. So I learned about pyrotechnics, and since then have presented more than 50 atmospheres and smoke sculptures in various locations.

You first displayed work in Toronto more than 30 years ago and have said you’re a fan of the city. What do you like about it?

I love Toronto, going back to the early 1980s when The Dinner Party was at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Since then, I’ve visited Toronto several times and always felt that the city and the waterfront were beautiful, clean and lacking in that horror in America: ubiquitous guns.

What was the inspiration behind your “A Tribute to Toronto” smoke sculpture?

I wanted to use colours that related to the environment, water and sky, thus my choice of purple, blue, green, yellow and white for this performance. We’ll ignite them in a carefully designed sequence so that they can merge with the wind and allow me to mix colour in the air.

My smoke sculptures are site-specific, and when Candice Hopkins, the Toronto Biennial curator, invited me to present one on a barge on the water, I was very excited. I’d never done one on a barge.

Did this new way of presenting your work create any challenges?

The fact that the barge will be 100 feet from the shore presented a challenge: how to make sure the piece has a visual presence to viewers on the shoreline. To help, I decided to create a scaffold structure that creates multiple positions for the coloured smokes, allowing for complex colour mixing— horizontally, vertically, from front to back on the scaffold and also from the barge’s deck.

It’s important to understand how long these pieces take to put together. We’ve been working on this sculpture for over two years including the site selection and smoke and colour tests.

Weather and wind can be fickle. Do you have to abandon a certain degree of control as an artist when working with smoke? How do you account for it?

Control isn’t what I’m interested in. Transformation is a better word as I believe that art can educate, inspire and promote change. The first step is personal transformation; perhaps that is why so many people have stated that my work changed their lives.

Years ago, people began to realize that my work challenged what is called Land Art, particularly that done by some of my male peers. While their work involves permanently manipulating and disfiguring the environment, my work is impermanent and meant to merge with light, wind and sky to create moments of intense beauty aimed at illuminating the natural world’s beauty.

Your exhibition at Daniel Faria Gallery is described as asking viewers to “contemplate their own fate as it is tied to the treatment of other species and the planet.” What can people expect to see?

In my exhibition, viewers will see a variety of works in which my ecological concerns play a major part. It begins with “Thinking About Trees.” I spent many months studying, drawing and thinking about trees and our dependence upon them. And yet they’re ravaged in clear-cutting and climate change–induced fires. We disregard what we now know are living things with a complex network of interactions.

There’s also “Before It’s Too Late,” a series of drawings and china-painted porcelains dealing with a variety of creatures in the Rio Grande valley, where we live, which are endangered. My last major project, works of bronze, ceramic and glass called “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction,” is among the exhibits as well.

How has COVID affected your art?

There’s a suite of 12 prints in the gallery show titled “Garden Smokes” that my husband, photographer Donald Woodman, and I did during the pandemic. It wasn’t possible to create larger smoke sculptures in New Mexico at the time due to fire regulations. Instead, we created small ones using the confined space of our gardens as a metaphor for the COVID-19 lockdown.

What other projects are you currently working on?

I’m working on too much. In addition to ongoing studio work and reprising my performance workshop—something I started back in the 1970s— I’m guiding the 50-year celebration of “Womanhouse,” the first major feminist art installation, which we did in Los Angeles while I was teaching at Cal Arts. Over the ensuing decades there have been innumerable projects based on “Womanhouse” all over the world, most recently a tribute exhibition in Los Angeles and one in Detroit that opens soon with women artists of colour.

Given the changes in our understanding of gender since the 1970s, this rendition of “Womanhouse,” located in Belen, New Mexico, is titled “Wo/Manhouse.” It was open to New Mexico artists across the gender spectrum. We received 90 proposals for 14 rooms. The selected artists are hard at work on their installations.