Claim of fake Norval Morrisseau painting hits a wall in court

Judge ‘doesn’t doubt’ accounts of a forgery ring in Thunder Bay, Ont., but rules disputed painting attributed to the famed Anishinaabe artist is authentic

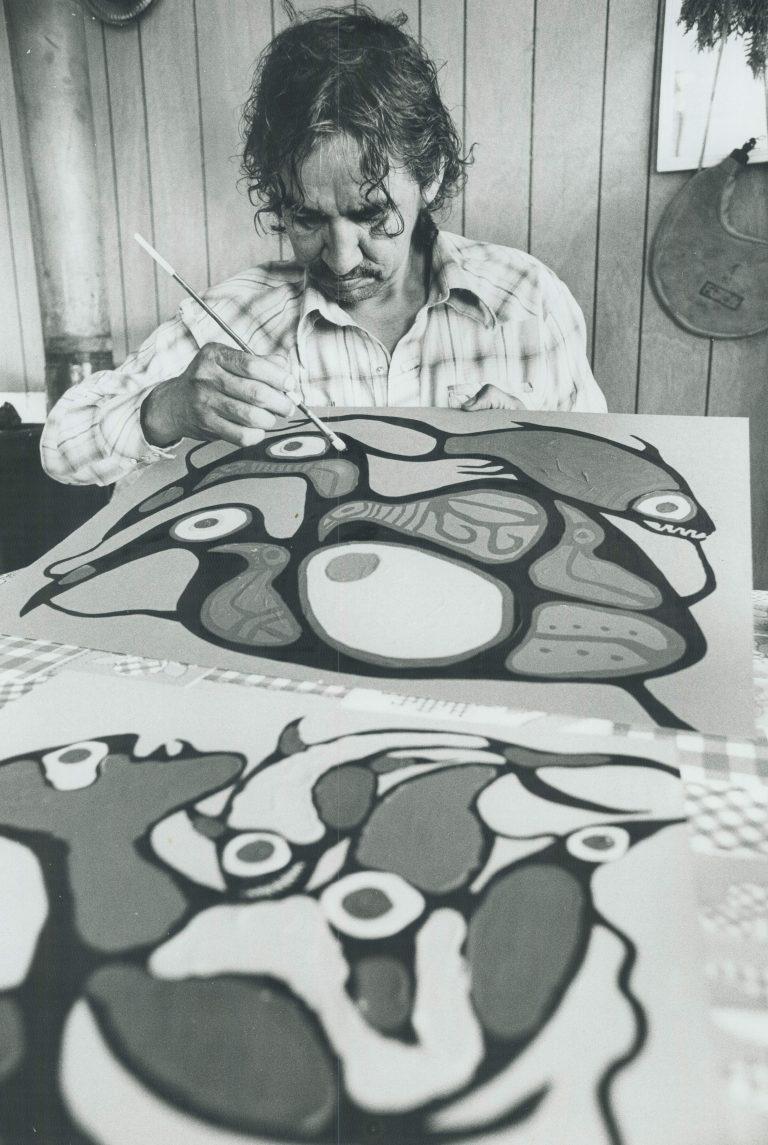

Norval Morrisseau. (Graham Bezant/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

Kevin Hearn, the keyboardist for the Barenaked Ladies, spent thousands of dollars going to court to prove that a painting he purchased more than a decade ago is a forgery. A Superior Court of Ontario Justice disagreed this week, ruling the painting is authentic on the balance of probabilities.

The case was the third to proceed to trial involving the authenticity of a painting attributed to Norval Morrisseau, an Anishinaabe painter considered to be one of the country’s most influential and important Indigenous artists. Since at least 2001, the market for Morrisseau paintings has been awash in allegations of fakes, creating uncertainty and depressing the value of his works. The dispute has partly centered on whether the artist signed the back of his paintings in English, with a title and a date, in black dry brush paint. Some contend Morrisseau only signed the name Copper Thunderbird, given to him during a healing ceremony, on the front of his paintings in Cree syllabics.

In his ruling, Justice Edward Morgan acknowledged the difficulties in proving (or disproving) authenticity. “While Spirit Energy of Mother Earth may indeed be a fraudulent Morrisseau, there is an equal chance it is a real Morrisseau,” he wrote. Legally, however, the burden of proof rests with the plaintiff. When there is a “tie,” Morgan wrote, the court must side with the defendants.

“We are absolutely shocked by the decision,” says Jonathan Sommer, Hearn’s lawyer. “We are very concerned by what we believe to be a number of very serious factual errors in the decision.” Sommer declined to elaborate, saying that Hearn is considering an appeal. “He’s bewildered and devastated by the decision,” Sommer says of his client.

READ MORE: How allegations of a forgery ring are threatening Norval Morrisseau’s legacy

In 2012, Hearn sued the Maslak-McLeod Gallery in Toronto and its owner for allegedly selling him a forgery called Spirit Energy of Mother Earth, dated 1974. Hearn came to believe his painting, which he bought in 2005, was forged after contributing it to a special exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. He was informed by museum staff that the curator of the show had the work removed and that it was “most likely a fake.”

The trial was held in December 2017 and this past February. By that point, the defendant and gallery owner, Joe McLeod, had died. Hearn proceeded with the lawsuit because he wanted to reveal what he believed to be the truth behind the painting. “People who had been seriously hurt in this environment where these paintings were made,” he testified. “I saw things I couldn’t turn back from. As much as this is about one painting, I had to do the right thing.”

At trial, Hearn’s expert witness was a Carmen Robertson, a professor in visual arts department at the University of Regina. She produced a 67-page report and testified about why she believes the painting is fake, including that the colour palette is inconsistent for Morrisseau’s work at the time, and that the brush strokes are out-of-character, along with other stylistic oddities. “While I genuinely respect the scholarly effort that Dr. Robertson has put into this analysis, I frankly am skeptical of its usefulness,” Morgan wrote. “It often has the feel of subjectivity hiding within a veneer of objectivity.”

Robertson also testified that the work, for her, lacked the spirituality and meaning seen in other Morrisseau paintings, which Morgan rejected. “Perhaps even more than beauty, spirituality is in the eye of the beholder,” he wrote. “Determining the authenticity of Spirit Energy of Mother Earth cannot turn on whether or not an expert has convinced the court that it actually has spirit energy.”

Morgan was not swayed by the fact that painting’s provenance could not be traced, writing that sourcing a Morrisseau is “as chaotic as his life itself.” Witnesses pointed out that “Morrisseau was in and out of jail, in and out of sobriety, and in and out of bad company,” he wrote. The judge’s ruling reads at points like post modernist theory: “What fills the void left by an inscrutable record of paintings is the viewer’s own background, experiences, and understandings.”

RELATED: Could art forgeries be even better than the real thing?

As for the disputed signature style, Morgan cited a previous court case involving an alleged fake Morrisseau. The trial judge accepted evidence in that case that the artist did sign his name on the backs of his works, and ruled the painting, called Wheel of Life, was authentic. (Sommer represented the plaintiff in that case, too.)

As Hearn’s case was proceeding to trial, an art collector and Morrisseau dealer named Jim White filed a motion to intervene. He was granted status in the case to essentially mount a defence, and produced a handwriting analyst as an expert witness. Kenneth Davies testified he had “a reasonable degree of certainty” the signature on Spirit Energy is Morrisseau’s, a position Morgan accepted.

The court also heard evidence from multiple witnesses about a fraud ring in Thunder Bay, Ont., run by a man named Gary Lamont, a friend of Morrisseau’s. Witnesses said Lamont sold hundreds of fake paintings, and his operation allegedly involved two of Morrisseau’s own family members. (Lamont is currently serving a five-year prison sentence for multiple counts of sexual assault.) However, there was no direct evidence linking Spirit Energy to Lamont. “I do not doubt the existence of a Thunder Bay-area fraud ring and the circulation of fraudulent paintings produced there,” Morgan wrote, adding, “since no one can identify Spirit Energy of Mother Earth at all, let alone having been produced by the fraudsters, the relevance of this evidence turns out to be tangential at best.”

Whether the decision will ultimately bring more certainty to the market for Morrisseau paintings is unclear. White testified that the questions of authenticity had done severe damage, but he’s now optimistic about the ruling’s potential impact. “It will help,” he says. “It won’t turn the tap on or off, but it will begin to show people what the truth is.”

Sommer is less certain. “I’m not sure where this decision leaves us,” he says, “given that the court has acknowledged the existence of a fraud ring producing Morrisseaus.”

Michael Panacci, the lawyer who represented White, is philosophical. “Perception is reality in art,” he says. “These rumours have been out there, and if they’re believed, they do damage. It’s all going to depend on the end viewer.”