This Winnipeg art gallery is a monument to Inuit culture

Qaumajuq is not just an art gallery or a stylish feat of architecture. It’s much more.

Share

It’s impossible to divorce Qaumajuq from Canadian history itself. The $55-million, 36,000-square-foot addition to the Winnipeg Art Gallery, or WAG, opened in March of 2021, housing the museum’s 14,000 permanent pieces of Inuit art—and 8,000 more on long-term loan. It’s now the world’s largest public collection of Inuit art, and a beacon of reconciliation reflected by its Inuktitut name: pronounced “KOW-mah-yourk,” it means “it is bright, it is lit.”

The work of finding a home for the collection began seven decades ago, when the gallery started acquiring carvings. “The WAG is 110 years old,” says Stephen Borys, Qaumajuq’s director and CEO. “Can you ever truly decolonize a colonial institution? That’s up for debate. But you can bring essential voices to the table.”

MORE: ‘Anybody want to drive this ambulance to Ukraine?’

The Los Angeles–based architect Michael Maltzan, who designed the gallery, was inspired by a 2013 research trip to Baffin Island, led by the WAG’s long-time curator of Inuit art, Darlene Coward Wight. Attached to Qaumajuq’s exterior is an undulating structure reminiscent of the Cumberland Sound icebergs Maltzan saw on his voyage. “When I came back, the main question was: how do I make something that infers the scale of the place where the art is made?” he says.

The design team chose Bethel white granite from Vermont for the top two-thirds of Qaumajuq’s facade, and flanked the first 20 feet of the building’s perimeter in glass, which contrasts with the WAG’s windowless modernist exterior. The glass also gives visitors an immediate glimpse of the show-stopping Visible Vault, a three-storey curved structure displaying close to 5,000 stone and bone sculptures.

The spaces within Qaumajuq have their own Inuktitut names. Jocelyn Piirainen, the museum’s associate curator of Inuit art, worked with the WAG’s Indigenous Advisory Circle, Inuit Elders and language keepers during the naming process. “The entrance hall is called Ilavut, which translates to ‘our relatives,’ ” says Piirainen, who is Inuk herself.

Members of Inuit communities received an early preview of the WAG’s collection, a space where the art of the North, their homeland, will be protected and celebrated. “It was wonderful to see them discover that their families’ work was in our collection,” Piirainen says. “It will hopefully inspire them to create things of their own.”

Skylights

Qilak is an 8,000-square-foot gallery whose name means “sky” in Inuktitut. It has 22 massive skylights—one of many ways Maltzan brought the outside in. They each measure 12 feet in diameter and 16 feet tall, and the light within is subtly altered by passing clouds.

Visible Vault

The glass vault has 492 shelves, displaying carvings from more than 1,000 artists and 31 northern communities. Its three-storey structure—two above ground and one below, where bone and antler sculptures are shielded from damaging light—showcases conservators, curators and researchers working in their element.

Exterior

Qaumajuq’s facade was inspired by the icebergs of Cumberland Sound.

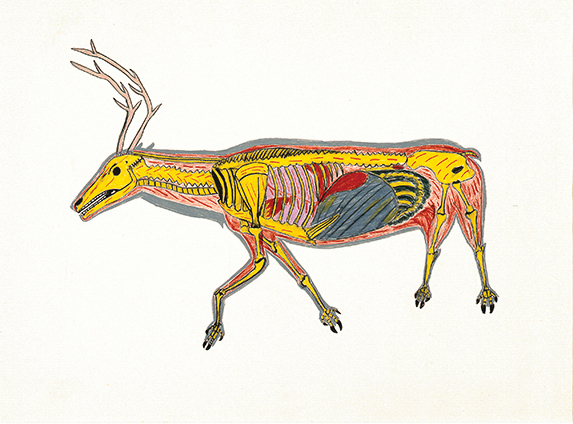

The Skeletoned Caribou (1974)

This work by William Noah, a graphic artist from Baker Lake, Nunavut, is part of Qaumajuq’s recent INUA exhibition.

RELATED: To my mother: ‘It’s still strange that home, for both of us, is now a different place’

Michael Maltzan

Maltzan is the founder and principal architect at the Los Angeles–based firm Michael Maltzan Architecture. His other notable projects include the Star Apartments complex in L.A. and MoMA QNS in New York.

This article appears in print in the June 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Northern exposure.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.