An esteemed author takes a crack at a new character: himself

Book review: A memoir from one of Canada’s greatest writers, Richard B. Wright

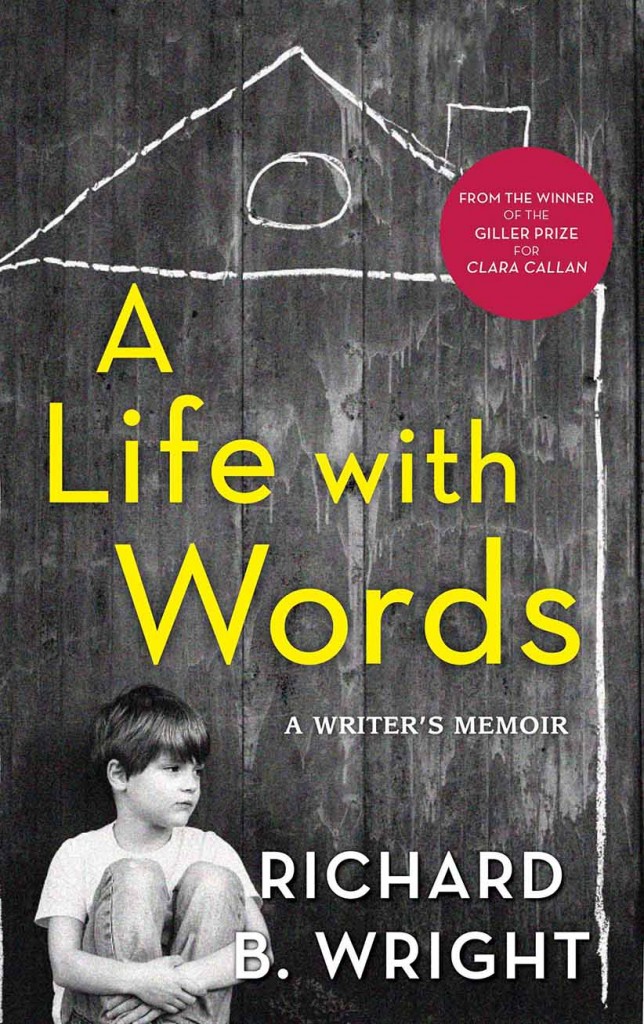

A Life With Words by Richard B. Wright

Share

A LIFE WITH WORDS: A WRITER’S MEMOIR

A LIFE WITH WORDS: A WRITER’S MEMOIR

Richard B. Wright

Without a doubt Richard B. Wright belongs to a select group of Canadian writers that includes the likes of Alice Munro and Mavis Gallant. His gift lies not only in his superior craft but in the way he uses extremely ordinary characters to dramatize profound, existential themes. His protagonists not only seek out the meaning of life; in their quiet way they contemplate the coordinates of human existence.

His comic first novel The Weekend Man, published in 1970, was culled from his experiences as a textbook salesman. He has written 12 books in all, the latter half of his career distinguished by acclaimed works such as The Age of Longing and Adultery. It is Clara Callan, however, that epitomizes Wright’s extravagant gifts. This Depression-era portrait of an unmarried teacher who loses her faith, is raped and engages in a torrid sexual affair, took home the Trillium, Governor General and Giller awards for 2001.

Now Wright has written this memoir, an account of how he inched his way toward a literary life. He was born in Midland, Ont., in 1937, in a working-class family. These were the final years of the Depression. His father painted buildings and raked leaves. At home, his mother’s lullabies, prayers and nursery rhymes thrilled him to the word. In truth, her words could both enthrall and disturb. She was a complaining, depressive person whom Wright loved, but kept at a distance. In time he came to see her as a kind of literary figure.

In A Life With Words Wright opts to depict himself as a literary character too, referring to himself throughout as the boy or the writer. Though this effort to present himself objectively prevents us from getting to know him as intimately as we do his characters, it is fascinating to observe him grow up and to watch a literary career evolve. A popular child, he likes best to play alone. He is in his teens when he undergoes a profound religious experience at a revival meeting. As a result he begins to study Proverbs, Psalms and the stories of the Old Testament. This is no surprise. Wright’s wielding of “the Word” is reminiscent of Marilynne Robinson’s. Though his characters frequently lose their faith, they wind up exchanging the power of the sacred word for literature, drama or poetry.

Wright’s religious fervour dissipated quickly, in part because he indulged in activities he thought God might disapprove of. For one thing, he liked to steal, and at Ryerson where he studied journalism, he engaged in countless affairs. By now it is the ’60s. But for Wright, beyond the notion of free love is sex as a natural part of human experience. It is an integral aspect of most of his novels.

A Life With Words is a modest memoir and also a kind of writer’s handbook. It has a lot to tell us about the long incubation of a literary dream. At the same time it encourages young writers to not give up. It took Wright years to believe a novel was an attainable goal; with every book he battled anxiety and depression—he called it “walking the red dog”—and he had to balance a nine-to-five job; he taught English to support his family. But the best thing about the book is the way it illuminates how Wright has transformed the experiences of his life into art. And vice versa.