Joshua Whitehead takes on CanLit

In ‘Making Love With the Land,’ Whitehead moves between genres and languages in a series of essays that open up a whole new window on the meaning of Canadian literature

(Photography by Tenille Campbell)

Share

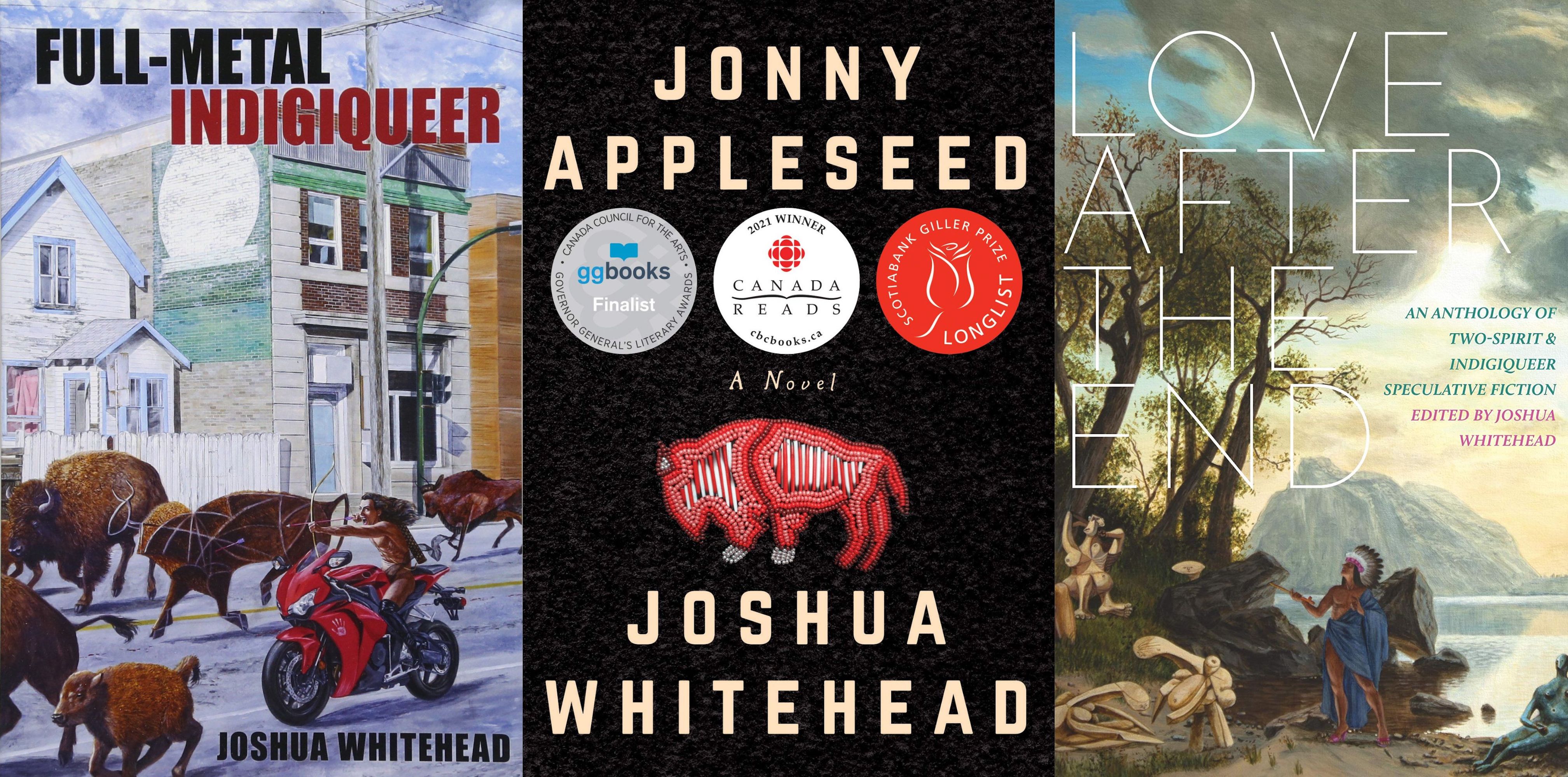

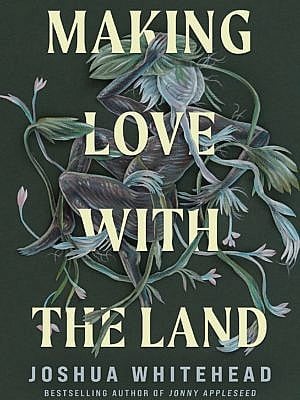

It has been an intense five years for Joshua Whitehead, marked by both personal loss and remarkable literary achievement. Since 2017, the Oji-Cree writer has published the poetry collection full-metal indigiqueer and the novel Jonny Appleseed, winner of both the 2019 Lambda prize for gay fiction and Canada Reads 2021. He’s also experienced the end of a long-term relationship, deaths in his family and, of course, the pandemic. Now 33 and a newly minted assistant professor of English at the University of Calgary, Whitehead has come out on the other side and continued his run of creative brilliance with Making Love With the Land, a collection of linked essays set for an August 23 release.

Making Love defies categorization, with elements of manifesto, memoir, apologia, literary theory, experimental writing and interior conversation colliding on almost every page. Throughout the book, Whitehead resists the strictures of Western genre and what he sees as the intrusive demands of readership and media. Equally striking is an effect he never set out to achieve: the whole of Making Love’s extraordinary parts comprise a bookend companion to Margaret Atwood’s 1972 classic Survival, the best-known and most influential book about literature in Canada ever published. Where Survival argued that Canadian writing was defined by settlers’ antagonistic response to this country’s harsh topography and climate, Making Love suggests that what shapes Indigenous literature is a much more mutually sustaining relationship with the land.

A child of Peguis First Nation in Manitoba, Whitehead was raised in the city of Selkirk, the son of a trucker father and a mother who worked at a shelter for Indigenous women. Growing up and attending school in mostly white Selkirk, Whitehead would beeline almost daily to the local library. He wasn’t there for the books, much as he liked to read, but for the internet access that allowed him to join online role-playing games and create digital personas. In his Making Love essay “The Year in Video Gaming,” Whitehead writes about his avatar, Zoa, in the game Lineage II, a character who later gave birth to the protagonist of the poems in full-metal indigiqueer. Zoa—“a muscle queen with a red mohawk”—enabled Whitehead to ignore a body the world around him didn’t value: “I was queer, Indigenous and fat,” he says.

He had another foot in Peguis, spending the better part of his summers there with his maternal grandmother and cousins of his own age. “My grandmother and aunties would sit around a table, drinking Red Rose tea and eating bannock, telling stories about snakes—you’ve got to visit Narcisse Snake Dens during mating season, it’s a wild sight—or about certain people they slept with at the bingo hall,” Whitehead says. “Sometimes it was horrific and sometimes it was fantastical and sometimes someone saw a UFO or dreamed of a thunderbird.”

Whitehead himself was a born storyteller—his parents still keep a box of stories and poems he told them. “They’re very secretive about it. I’m always trying to find it,” he says. He describes himself as a muckatoon, using a Cree term he defines as meaning “unabashedly verbose.” But his Cree remained rudimentary through his youth, and he was drawn to the likes of Ursula K. Le Guin, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. “I was trained, like we all are, really, to write white,” he says.

After graduating high school, Whitehead attended the University of Winnipeg, majoring in psychology. By 2010, he had dropped out and was working the night shift at Subway. (“I was basically paid to read and eat subs,” he fondly recalls.) But he soon grew restless. He returned to the University of Winnipeg and enrolled in a course dedicated to Toni Morrison. “We read Beloved first, and everything kind of clicked in my brain,” he says. “I will always credit Toni Morrison, all of her work—the vernacular use, the morality, the use of temporality to mix past, present and future—as teaching me how to not write white.”

In 2017, he began studying for his Ph.D. at the University of Calgary, where his department required a second-language credit, which presented a conflict—and an opportunity. “I refused to have another colonial tongue,” Whitehead says. He enrolled in a Cree course at the university, his first and only formal one. Now he tries to practise every day and describes the My Cree app on his phone as one of his best friends. “I grew up listening to a mix of Cree and Anishinaabe. There’s quite a bit of crossover between them, with small inflection changes. Learning unlocks a lot of memories from childhood. Even the alphabet felt like it was lying dormant in me.” His full-metal poem “mihkokwaniy” is about his paternal grandmother Rose Whitehead’s 1962 murder; the title means “rose” in Cree. Some of its most plangent lines intertwine personal tragedy and cultural genocide: “what would life have been like / if you had lived beyond 35? / would i be able to speak cree / without having to google translate / this for you?”

Whitehead looked outside of contemporary Western terminology for the best way to express his sexual identity. Though others saw him, rightly enough in his opinion, as a gay fem cis man, he did not find a true fit with these identifiers. “ ‘Gay’ was too white. It was too classed. It was able-bodied,” he says. “You look at Pride festivals—which I do completely understand and I do partake in—but they’re just slashed by whiteness, slashed by masculinity. The participants are dancing on the back of these banks that are actively putting pipelines through Indigenous communities.” He tried out being “queer,” which was better because it was more politically radical, but in the end, it didn’t have the ancestral credibility he was seeking. The iconic 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City, which are widely considered the birth pangs of contemporary gay liberation, are only minutes in the past, Whitehead says, compared to the long history of thinking about gender and sexuality and community among Indigenous people. In “two-spirit,” which reflects these concepts, Whitehead found the language he needed. He also applies Indigiqueer, a more sexualized and Westernized term, to himself.

Whitehead’s evolving ideas about language and literature, along with developments in his life—including debilitating bouts of insomnia and anxiety—are all visible in Making Love. But for sheer cerebral and emotional rewiring, little matched his 2018 promotional tour for Jonny Appleseed. The novel tells the story of a two-spirit Indigiqueer youth who leaves his Manitoba reserve and becomes a cybersex worker in Winnipeg. Whitehead allows that he and Jonny are “embryonically tied,” but he is adamant that the character is not him.

Yet, while touring for the book, Whitehead was often addressed as “Jonny” by interviewers. (“I should have given him a different consonant,” he says.) Sometimes they probed for revelations of real-life trauma that could explain the Jonny’s experience. Whitehead calls this “extractive questioning”—focusing more on biography than text. As a novice writer who was eager to please, Whitehead automatically responded to these questions, often to his regret. After he answered a journalist’s question about the possible influence of his paternal grandmother’s murder on Jonny Appleseed, Whitehead was racked by grief and anxiety. He reeled around downtown Toronto until he found himself in the Eaton Centre, sitting in the food court, sobbing uncontrollably.

The tour was a lesson in the quid pro quo of a writer’s life in a market economy. Whitehead describes author and book as being laid out on a slab, open to what he flatly calls an autopsy. “It happened with any type of reporting or Q&A or book signing: ‘Tell me something real about your life. What limbs have you lost? What pain have you experienced that will legitimize this book for me?’ ”

All authors are open to that kind of metaphorical autopsy, but BIPOC authors far more so, and—in Canada at least—Indigenous ones most of all, even when their forensic dissectors are sympathetic readers. Whitehead points to what he calls the non-Indigenous “starving hunger” for residential school trauma narratives. “I definitely have the utmost respect for residential school survivors, and I think their stories should be told,” he says. “But Indigenous writers have so much more to give. I don’t want residential school stories to be the synecdoche for Indigenous writing.”

For a writer repelled by the idea of having to reveal all to the world, adopting a universal second-person in Making Love was an effective way of presenting an authorial persona rather than a real and vulnerable person. “I love, love the pronoun ‘you.’ I began using it in the essays to address ex-partners, aggressors in my life, and some very specific writers and audience members at festivals. Just levelling the playing field,” says Whitehead.

Cree also bolstered his defences. It doesn’t have genders, which is liberating for a two-spirit writer, and it animates things like rocks, mountains and waters. This led Whitehead to think about animating his experiences of insomnia and anxiety, seeing them as symbiotes that bring benefit along with their damage. Insomnia is a tool of the writerly trade, for example, and anxiety an ancestral warning to stop what he is doing. Even rendered in the Roman alphabet, Cree words like nicimos (lover), which readers can translate online with relative ease, offered Whitehead some protective distance from the text.

So did Cree syllabics, the building blocks of its written form. “A Geography of Queer Woundings,” one of the book’s more visceral personal essays, opens with a bureaucratic-sounding list of pain: “Loss, mourning, sexual assault, abandonment, colonial violence, imperialism, state-sponsored genocide—all of which, for me, normalizes an absurd fact of Indigenous life: it hurts to live.” The essay is also full of syllabics, making it nearly impossible to read for those who don’t know the Cree alphabet. That is on purpose. “To remove myself from the autopsy table,” Whitehead says, “I had to ghost myself into Cree.”

Whitehead has been straddling borders his whole life. That experience is what he wants to write about, and on his own terms. “From an Indigenous perspective, he’s asking you as a reader to make incredible leaps, between languages, between experiences, between histories,” says Lynn Henry, Whitehead’s editor at Knopf. “He is not only breaking down genre, but breaking down language itself—putting Indigenous words alongside English words and allowing them to disrupt each other.”

For all its subtly expressed thought, intense personal detail and unconventional storytelling, for all Whitehead’s success in portraying himself as an indefinable “mirage in the middle space between languages,” what makes his new book so compelling is the way it matches up with Atwood’s Survival. The two books can seem like polar opposites—one the settler colonial tradition, the other the Indigenous—right down to their titles. But they share profound similarities, too. They speak for literature that almost always carries a note of “we are still here,” and make the case that the stories and writing they describe are at once distinct and universal. That is the core of Whitehead’s new book. It makes plain that Indigenous literature arises from very different ways of thinking, feeling and living but that it’s also as Canadian as Atwood and Munro, and as universal in its meaning and importance.

This article appears in print in the August 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here, or buy the issue online here.