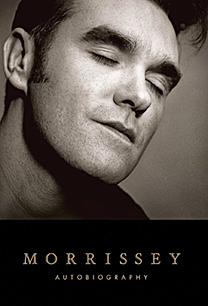

Autobiography

Autobiography

by Morrissey

When applying the Churchillian concept of a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma to musicians, there are few, if any, who are better fits than Steven Patrick Morrissey. A wide swath of his multitude of fans would be hard-pressed even to identify his first and middle names. So it is hardly surprising that, prior to the U.K. publication of his Autobiography last October (and its arrival in North America two months later), anticipatory speculation ran wild. What would the notoriously inscrutable Morrissey divulge? Anyone hoping for a straight-ahead account of his history with the Smiths and subsequent solo superstardom or specifics of his personal life will be disappointed. So jejune an approach would, no doubt, have been anathema to him.

Remarkably, and rather delectably, unorthodox it indeed is. He is a gifted, if florid, writer with a sometimes frustrating, sometimes fascinating penchant for diving headlong into narrative rabbit holes. The text can be as tangled and dense as underbrush, yet is far more often as powerfully poetic as, well, a Morrissey lyric. Autobiography tends to be a Moz pit of misery, beginning with a Manchester childhood and adolescence of Dickensian grimness and abject aimlessness, alleviated only by the redemptive music of David Bowie, Patti Smith, Bryan Ferry and, above all others, the New York Dolls. The glumness continues through the Smiths’ rise and fall and Morrissey’s phoenix-like re-emergence. He relentlessly—albeit colourfully—harangues the the music business on both sides of the Atlantic for its ignorance (in all respects) and disinterest. His strongest vitriol is reserved for the mid-’90s trial resulting from Smiths drummer Mike Joyce’s headline-grabbing suit, seeking back-payment of 25 per cent of the band’s earnings, with Morrissey railing against Joyce and presiding judge John Weeks for nearly 50 pages.

Still, amid all the bleakness, he maintains a marvellous, mostly self-deprecating, sense of humour. Morrissey knows he can be a pious, preachy pain in the arse and, regularly, delightfully calls himself out. (Though one subject—the mistreatment of animals and, relatedly, mankind’s carnivorous nature—is sacrosanct, and he savours tales of exiting restaurants whenever his dinner companion orders anything that once drew breath.) Apart from a fixation with album sales, chart positions and concert-attendance figures, all meticulously documented, this is less a collection of facts than feelings, all deeply, painfully—and, occasionally, joyously—felt. He suffers no fools, allows no compromises, makes no apologies. “I am impossible,” he concludes. Ah yes, but captivatingly so.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary