Brian D. Johnson: 1 month, 0 movies

A film critic escapes the screen for the lake and the page

Share

I just spent a month without movies. Not one, not even a DVD. Usually I see four or five movies a week, and about three a day during festivals. So this was a radical retreat from the screen. A film fast. I was in a cabin on a Quebec lake with no TV, just a laptop with limited Internet and a pile of books. It wasn’t quite like David Denby taking a full-on sabbatical to immerse himself in the classics. My books spanned extremes of low and high culture, from Fifty Shades of Grey to Swann’s Way, with many shades in between. I’m embarrassed to say I dragged myself to the end of the E.L. James tome but just dipped into Proust periodically without ever finding traction.

Did I miss movies? Not really. I felt I was still watching them, on the page. In the absence of film, what intrigued me is how every book I read took on cinematic dimensions—whether I was reading a Lee Child paperback and trying not to imagine Tom Cruise (who has been wildly miscast as the 6’7” Jack Reacher), or parsing Memorial, an elixir of brilliant poetry distilled from The Iliad that is as graphically violent, and tender, as any movie I’ve seen.

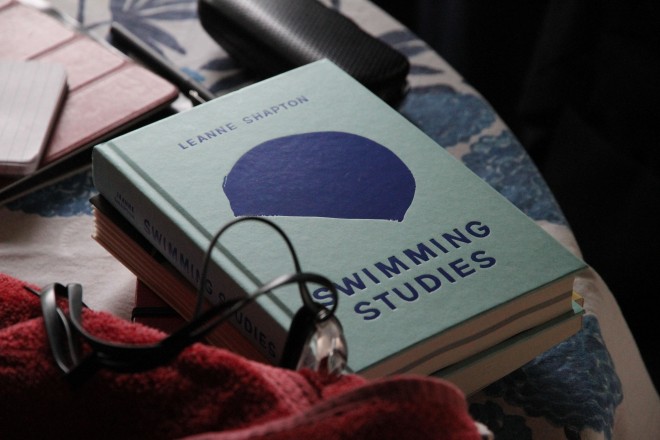

But the book that struck closest to home was Swimming Studies, a sublimely unconventional memoir by Leanne Shapton, who grew up in my childhood suburb of Etobicoke, in Toronto’s west end. Displayed on a table at Indigo, her book caught my eye at once: a pale blue hardcover designed like an old-school textbook and daring to go naked without a dust-jacket.

Then there was subject matter. In this overheated summer, swimming became something of an obsession: I got into a daily routine of leisurely 2 km laps to the end of the lake and back. But Shapton swam in a whole other league. A former art director with Saturday Night and the New York Times, this New York-based writer and illustrator was once a competitive swimmer, reaching the Olympic trials in 1988 and 1992. But despite the Olympic trials and Olympic-sized pools, on the first page she hastens to point out, as she has done so often, that she was not an Olympic swimmer. In other words, it’s not that kind of book.

Swimming Studies is a unique mix of memoir and meditation, one that takes us from the grueling rituals of early-morning training in cold chlorine to recreational bouts of ocean swimming and delinquent pool jumping. Shapton confesses to a fear of open water. She likes the security of the lane, with a wall beside her. For me, it’s the other way around. I feel claustrophobic in a lane and ecstatic in an empty lake.

Shapton treats swimming as a medium for a deeper meditation, as memories of suburban family life glide by like a series of Impressionist silk-screens. She writes like a painter, letting her life unfold as a non-linear suite of laps, strokes—and brushstrokes, literally. Her text about life in and around the water is paced with her own water-colours, and an archival photo gallery of her many bathing suits.

Visually designed with a keen eye inside and out, the book is an utterly original objet. It could be called Portrait of the Artist as a Young Swimmer. Even the author’s episodic, lap-by-lap prose feels art-directed, powered with a fluid economy of line. And as she writes about eventually finding her vocation in art, all those mantra-like strokes of memory begin to add up to something more conceptually coherent than you’d expect. Learning that artist Cy Twombly is the son of a swim coach, she writes: “I start to see Twombly’s paintings as thrashing laps, as polygraphs, as a pulse rate.” Or, in the eyes of this film critic . . . a frame rate.

Alice Oswald’s Memorial, a slim book of exquisite poetry, was also a fine swimmer’s companion, with lines like these:

He was knocked backwards by a rock

And sank like a diver

The light in his face went out

Like the shine of a sea swell

Lighting and flattening silently

When water makes way for the wind

Her book chronicles the violent deaths of some 200 characters in Homer’s Iliad, and begins with their names simply listed on eight pages, like a print version of Washington’s Vietnam War memorial. Each death is followed by a one-stanza simile, which is then repeated word for word. You could choose not to read it again, but you do and the second time around it feels different. There are moments of violence worthy of Tarantino:

And PEDAEUS the unwanted one

The mistake of his father’s mistress

Felt the hot shock in his neck of Meges’ spear

Unswallowable sore throat of metal in his mouth

Right through his teeth

He died biting down on the spearhead.

And what about Fifty Shades of Grey? I read it out of duty—figuring I should check out a pop culture phenomenon that everyone was talking about—while secretly hoping it would be a hot read. Of course, it’s depressingly bad, and not hot at all. It’s S&M for Dummies, a jejune fantasy of pasteurized eros. The relentless clichés reminded me of the Hardy Boys books I read as a child, and though the email repartee between the gob-smacked ingénue and her tycoon dreamboat has a few flourishes of wit, I found myself skipping the tedious sex scenes after a while, eager to consummate the soap-opera, while wishing I was watching Girls.

The only consolation is that the movie franchise—which is inevitable—could not possibly be worse . . . or could it?

Now as TIFF looms, it’s time to go back to the movies with a fresh eye, and fond memories of a widescreen lake where a pair of goggles served as 3D glasses.