Protecting a mother’s memories from Alzheimer’s: Book review

Mother-daughter Alice in Wonderland-like exchanges underline this remarkable child-as-parental-caregiver memoir, writes Anne Kingston

Share

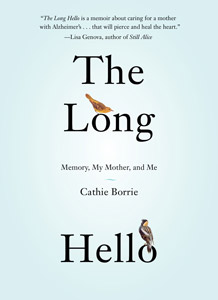

THE LONG HELLO: MEMORY, MY MOTHER AND ME

Cathie Borrie

When her 86-year-old mother entered Alzheimer’s twilight, Cathie Borrie started to tape their conversations. She wanted to remember her mother, of course, but more her often-startling verbal utterances.“I love looking into your voice,” she’d say, or refer to the “upside-down language” of birds’ chirping. “I want to keep the words of my new poet mother,” Borrie writes.

Mother-daughter Alice in Wonderland-like exchanges underline this remarkable child-as-parental-caregiver memoir, an emerging genre. Constructed in prose fragments that capture the many facets of caring for a dying parent, the book also serves as a meditation on the elusiveness and selectivity of all memory.

Woven throughout is Borrie’s own life story, one riven with loss, which elucidates her devotion to her mother: a strong woman who fled an abusive husband, taking with her Borrie, then five, and her younger brother, who died tragically at age 13, beaten by another boy. Her mother’s remarriage to a businessman brought financial stability to the family—though cast Borrie adrift at boarding school.

Borrie’s candour is wrenching. She describes becoming mother to her mother, against the wishes of both, the sadness of watching her personal historian forget who she is, and the difficulty of hearing unfiltered truths about her mother’s life with Borrie’s father.

Borrie, a former nurse, is also unflinching in chronicling modern medicine’s clinical barbarity—a years-long relay of doctors, drug stores, hospitals, home-care stores, with no prize at the end, only a tortuous hospital death. She herself copes with a diet of “tandoori chicken, chocolate, wine, sleeping pills,” and the occasional “breath in 2-3, out 2-3” of Latin dance class, with her mother never far from mind: “I am choreographing a dance for my mother and me.”

She succeeds by recasting a disease typically measured by loss in terms of what also can be gained. Toward the end, as her mother copes with a brutal cough, Borrie gently touches her chest: “Is there enough compassion in there?” her mother asks. “Yes, Mum,” Borrie answers. “It’s full, beautiful.” The same can be said for her daughter’s remarkable book.