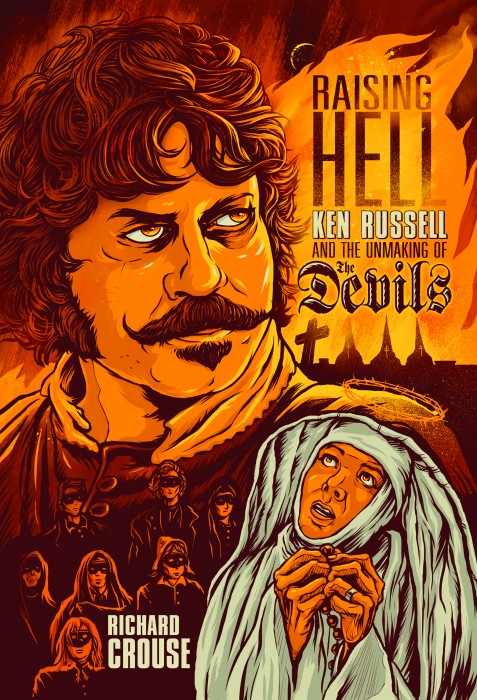

Review: Raising Hell: Ken Russell and the Unmaking of the Devils

By Richard Crouse

Share

Nunsploitation. Now there’s a sub-genre we don’t hear about every day. (And no, The Sound of Music does not qualify.) The Devils, Ken Russell’s incendiary spectacle of sex-crazed nuns, is one of the most controversial films ever made. Although Russell, who died last year, was an Oscar-nominated filmmaker (Women in Love) and his cast was led by Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, the ebullient blasphemy of his 1971 cult classic remains so stigmatized that Warner Bros. still refuses to release the director’s cut on DVD four decades later. Richard Crouse, film critic for CTV’s Canada AM, shows a lot of nerve in writing a book about an almost forgotten film that few people have seen. But Raising Hell, which has drawn raves from the likes of David Cronenberg and Guillermo del Toro, is a fascinating chronicle that illuminates Hollywood’s most fundamental taboos.

Nunsploitation. Now there’s a sub-genre we don’t hear about every day. (And no, The Sound of Music does not qualify.) The Devils, Ken Russell’s incendiary spectacle of sex-crazed nuns, is one of the most controversial films ever made. Although Russell, who died last year, was an Oscar-nominated filmmaker (Women in Love) and his cast was led by Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, the ebullient blasphemy of his 1971 cult classic remains so stigmatized that Warner Bros. still refuses to release the director’s cut on DVD four decades later. Richard Crouse, film critic for CTV’s Canada AM, shows a lot of nerve in writing a book about an almost forgotten film that few people have seen. But Raising Hell, which has drawn raves from the likes of David Cronenberg and Guillermo del Toro, is a fascinating chronicle that illuminates Hollywood’s most fundamental taboos.

Set in 17th-century France, The Devils is based on the true story of 27 Ursuline nuns in the walled city of Loudun who claimed to be possessed by demons under the influence of Father Urbain Grandier, who was burned at the stake. Most likely, he was a political victim of Cardinal Richelieu, while the nuns’ sex-crazed displays of “witchcraft” were induced by exorcists. The film was based on Aldous Huxley’s book The Devils of Loudun (1952), which relied on eyewitness accounts. Its most inflammatory scene is an orgy/exorcism known as the Rape of Christ, in which naked nuns use a life-sized crucifix as a sex toy—footage that got chopped by censors and was lost for over three decades.

Crouse reconstructs The Devils in meticulous detail, from Russell’s arduous shoot to the hysteria surrounding its X-rated release. Arguing for the film’s place at the cutting edge of ’70s cinema, he notes that censors treated The Exorcist with kid gloves just two years later. What’s different is The Devils’ potent mix of sex and religion—and its vision of a corrupt Church that “uses possession as a tool to intimidate and manipulate the innocent.” History, in the hands of an unflinching filmmaker, can be more graphic than fiction.

Find news, reviews and all things literary at the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog.