Rogers Writers’ Trust: Spotlight on Kathy Page

We asked the 2018 nominees: Who are you writing for, who is your imagined or intended reader?

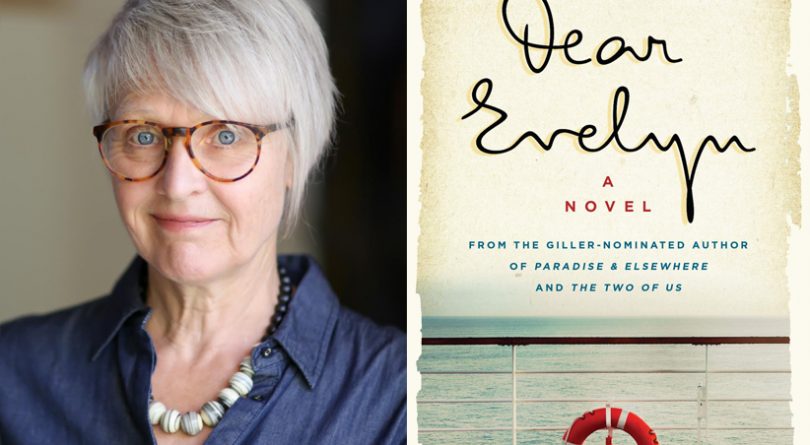

Kathy Page

Share

Kathy Page is nominated for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for her novel Dear Evelyn, “a startling tale of time’s impact on love and family,” according to the prize jury, “as well as one’s complex search for personal meaning and truth.” The winner will be announced at the Writers’ Trust Awards ceremony in Toronto on November 7. The winner receives $50,000. Each nominee receives $5,000. During the weeks leading up to the event, Maclean’s will publish an excerpt from each shortlisted writer, along with their answer to this one question: Who are you writing for, who is your imagined or intended reader? Here is Page’s response.

This changes a little from book to book. With Dear Evelyn, I am writing for anyone who has an intimate partner of some kind, or wants to, or once did—and also anyone who wonders about the intimate relationships of other people, and especially of their parents. I’m writing for anyone who is curious, and who cares about how we connect. I’m also writing for myself, to make something—a story—out of experience.

Excerpted from Dear Evelyn, copyright © 2018 by Kathy Page. Published by Biblioasis. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

“Bite on this,” Mavis said, and gave Adeline a half-moon of leather on a string that tied around the wrist: her own invention, she said. Adeline knelt, legs wide, arms thrown over the edge of the double bed, the top of her belly pressing into it. Mavis had rolled back the rug and put down newspaper topped with clean sheeting. Same on the bed. Bleach in the washing water. Cleanliness. Keep visitors away. She had boiled everything sterile, scrubbed her hands three times. “Bite,” she said, “not long now.”

The second baby was supposed to come easier, but this little bugger had started off facing out. To bring it round, Mavis had made Adeline crawl up and down the tiled passageway on her hands and knees, time after time, then stand and lean on the end of the bed. Two days. Very little rest. But be grateful it isn’t a breech. And be grateful she isn’t at York Road: a filthy place, and half the mothers there come out in coffins. And no high and-mighty doctor charging you the earth. Mavis cost fifteen shillings, however long it took.

Adeline groaned, bit down hard, and when the worst had passed, she spat the leather thing out and a bit of one of her back teeth went with it. She didn’t care.

“On your side on the bed, if you don’t want to tear,” Mavis said.

“No,” Adeline told her as the pain obliterated all remaining thought and forced a grunt out between her clenched teeth. Spit oozed out over the leather thing and ran down her chin, but Mavis got her up on the bed before the next one. A good thing. Her legs were shaking so much she might have sat on it.

“I’ll be damned!” Mavis said, minutes later. The cord wound three times round the baby’s neck—no wonder he was slow to emerge. She slipped her finger under one of the fleshy loops and tugged it free.

Male, unremarkable, Mavis wrote on the record. Father, Albert Edward Miles, lathe operator. Mother, Adeline Miles. They didn’t have a boy’s name picked, so Mavis recommended Harry: “Can be a Henry or a Harold. Works for a king, a ditch-digger, or anything in between. Everyone likes a Harry.” Albert’s grandfather had been the Henry sort so he was happy with that; Adeline was too tired to care.

Albert took a spade and buried the afterbirth in the square of yard out back, near the outhouse. Put in a tomato plant on top of that, Mavis advised him, though there was not enough light there for anything but the toughest weeds to grow. She brewed tea and waited two hours in case of bleeding and then he paid her the balance owing and a shilling tip for a good job done.

Adeline’s baby sister Josephine, seven years younger, was married, too. When Adeline turned weepy and couldn’t pull herself back together she came over, got her out of bed, and brought her downstairs to sit in the small back room, its windows fogged with the steam from soup-bones boiling.