The very checkered history of the men’s suit

Christopher Breward grabs a thread from the suit’s seams

Share

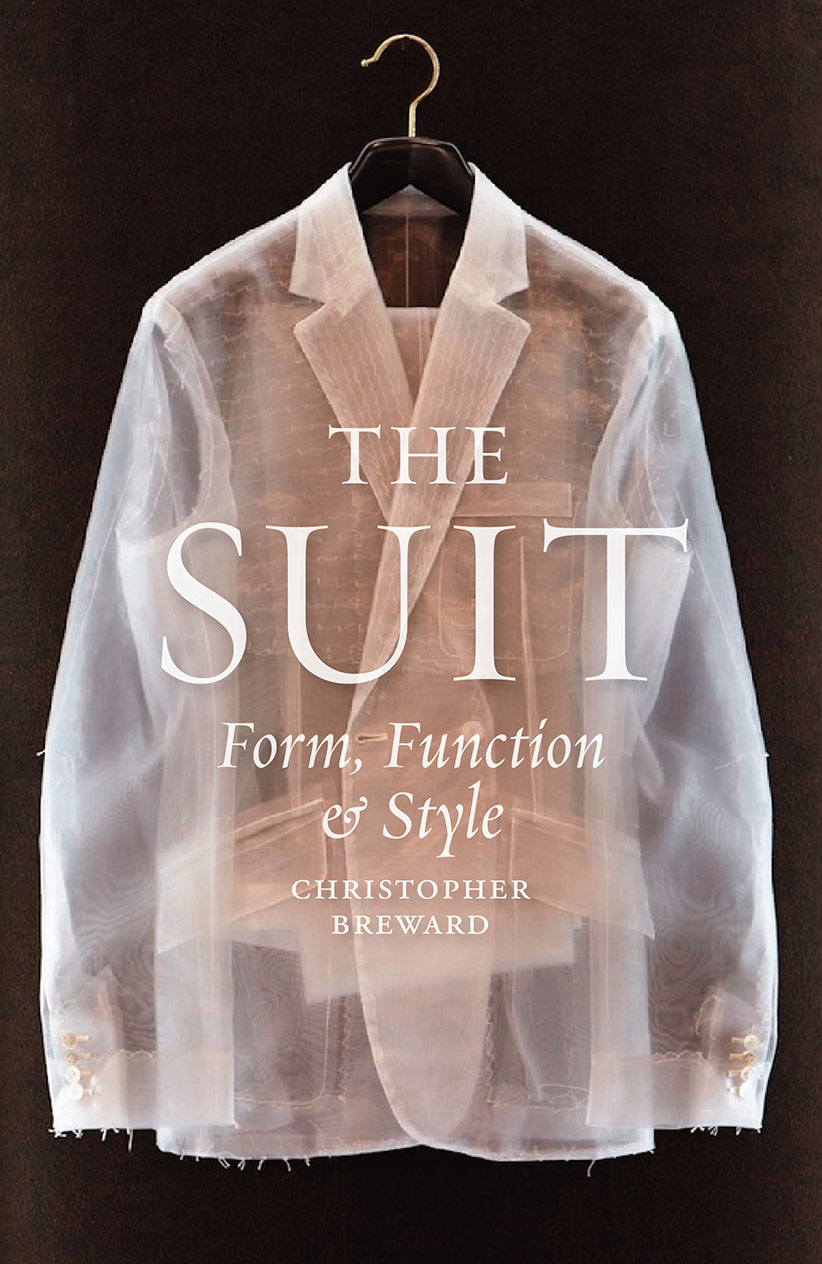

THE SUIT

By Christopher Breward

The ubiquity of the suit in everyday life makes it easy to forget that it is a unique garment with a long history that has never not been invested with meaning much greater than its drab uniformity would suggest. Christopher Breward, a professor of cultural history at the University of Edinburgh, grabs a thread from the suit’s seams and doesn’t stop pulling until there is nothing but a pile of rags on the floor.

Those rags, and the suits that they make, have tended to be a top-down affair. From Charles II’s introduction of the waistcoat through the dandified Beau Brummell and Oscar Wilde to today’s Instagram celebrity peacocks, men’s fashion has followed an elite coterie of well-draped dressers as the arbiters of good taste.

But fashion and the suit are rarely the same. Breward never lets us forget that this story is one of renunciation. The movement away from the elegantly embroidered cloth and sumptuous silks of European court life and toward dark-hued wools reflects the egalitarian ethos of burgeoning democratic societies; the move from the Victorian and Edwardian-codified morning dress to the simpler lounge suit (the technical term for the one we wear today) reflects the birth of leisure and a relaxation of social mores in the years before, during, and after the First World War. In the years since, it has become tabula rasa, capable of expressing everything from traditional ideals of power and order to our deepest insecurities about gender and identity. From the man in the grey flannel suit to the era of zoot suits and tight-trousered mods, the suit encompasses both culture and counterculture.

It’s a fascinating story, and one that occasionally gets lost in Breward’s excessive attention to the suit examined through the lens of cultural studies. While it is fascinating to sound the adumbrations of the garment from cultural figures as diverse as Le Corbusier and David Byrne (whose expanding suit in the 1984 film Stop Making Sense is as iconic as a Bond tuxedo), the suit as it actually exists—as something people wear to everything from job interviews to weddings to summits with world leaders—never materializes.

This failure to take the suit on its own terms leads to some of the book’s more confusing moments—for instance, the equation of Cary Grant’s untarnished attire in North by Northwest with the holy trinity of the suit as signifier. The fact that Cary Grant was a movie star who just wanted to look sharp is never considered, and so the power of the suit—and its ability to project power—gets lost in readings so deep they lose sight of their subject.

In his quest to see how the suit has been refracted through culture, Breward misses the most interesting fact about suits: people still wear them.