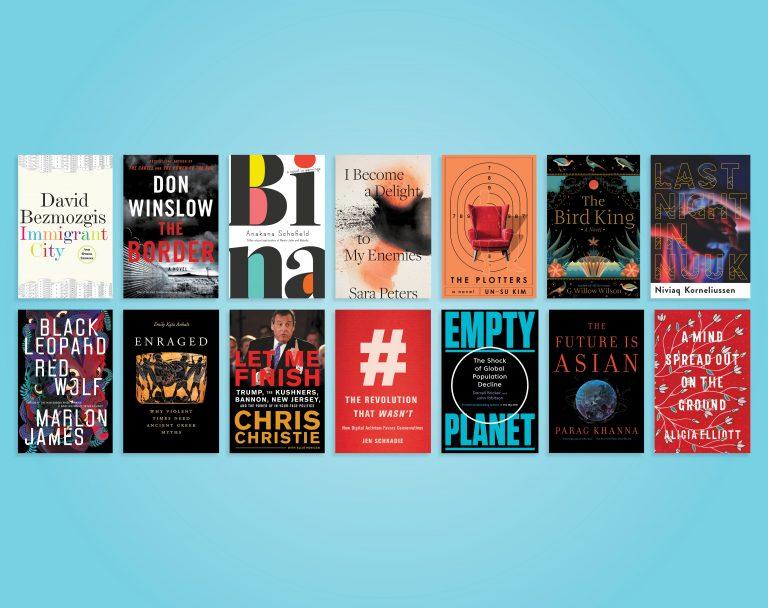

These are the books you need to read in 2019

More Trump, memoirs and Ian McEwan: Many titles evoke the U.S. leader, but there’s respite, and even the devil, in fiction

Share

Some literary tides are painfully slow to form. George R.R. Martin’s devotees are starting to resemble Toronto Maple Leaf fans—their yearning for deliverance, whether a Stanley Cup or another Game of Thrones volume, isn’t dead, but it is well (and wisely) banked at the moment. Other tides seem unstoppable. If there is a single word to sum up non-fiction this year and next, it’s “Trump.” That’s true outside America and even for books not specifically about the 45th U.S. president: it’s not likely that publishers would be as interested in studies of right-wing populism without him. Authors haven’t ceased writing about global issues, from migrant crises to sex trafficking, but the looming presence of Donald Trump—and what he symbolizes to detractors and supporters alike—is felt in them all.

The fiction of 2019 should provide some relief, depending on what a reader brings to it. But it will be difficult to delve into the short stories in Immigrant City, David Bezmozgis’s first book since his two novels were shortlisted for the Giller prize (in 2011 and 2014), without thinking of America’s xenophobe-in-chief. The same applies to The Border, the concluding volume in acclaimed thriller writer Don Winslow’s Cartel trilogy, in which a DEA agent discovers the incoming U.S. presidential administration is in bed with narco-traffickers.

Some reprieve should be provided by Bina, a mystery-haunted, blackly funny “novel in warnings” narrated by an anguished woman. It’s by 2013 Amazon.ca First Novel Award-winner Anakana Schofield (Malarky), perhaps the most arrestingly distinctive writer in Canada, whose style and themes never remind readers of anyone else. Originality is also a hallmark of Nova Scotia native Sara Peters’s I Become a Delight to My Enemies, which uses different voices and whipsaw changes in literary form to explore the inner lives of women in one weird town. It’s the first title issued under Penguin Random House’s new Strange Light imprint, dedicated to “unpredictable, experimental, diverse and emerging authors.”

There are highly anticipated books from more mainstream writers, too, including Deep River, a family saga set among Oregon loggers a century ago, and the first book of any kind in eight years from Karl Marlantes, author of the Vietnam War classic Matterhorn. Then there’s the ambiguously titled Machines Like Me, the 15th novel in Ian McEwan’s illustrious career, an alternate-reality story of artificial intelligence and natural love, and Radicalized, four science-fiction novellas by Canadian-British author Cory Doctorow woven into a novel by common social, technological and economic themes. And Dave Eggers’s The Parade is vintage Eggers, cryptic and political, featuring two antagonistic American contractors—known, for security reasons, as Four and Five—building a road in a lawless foreign country.

What will surely make the biggest collective splash in 2019, though, is an eclectic array of new voices writing from new perspectives, telling their stories against unfamiliar backdrops. Un-su Kim’s nihilistically funny page-turner, The Plotters, set in an alternate Seoul where competing assassination guilds dispatch operatives to solve customers’ little problems, will rightly push Korean noir into the limelight. Contrast that with an English translation of the massive Japanese bestseller by Genki Kawamura, If Cats Disappeared From the World, in which a terminally ill postman allows the devil to remove an item from the world and its collective memory in exchange for another day of life. No problem, in this goofy-sounding but ultimately profound meditation on life and death, until the devil overreaches by casting his eye on Cabbage, the postman’s beloved cat.

In The Bird King, G. Willow Wilson, a prominent American Muslim woman author known for her subtle graphic novels and award-winning fantasy Alif the Unseen, turns to historical fiction with a love story set during the dying years of Muslim Spain. Last Night in Nuuk, the English-language launch of 28-year-old Niviaq Korneliussen, Greenland’s rising literary star, is a very contemporary multi-character coming-of-age story that unfolds in the Arctic island’s capital. But the most extraordinary read of them all may be Black Leopard, Red Wolf, a riveting immersion into a mythic African landscape by Marlon James. Fantasy has been struggling loose from the grip of its medieval European roots for years now, but the Jamaican author’s hallucinatory writing and literary reputation—James won the 2015 Man Booker Prize for A Brief History of Seven Killings—will speed the process.

In counterpoint, the year’s non-fiction is like a cold bath. And sometimes that’s a good thing, writes classicist Emily Katz Anhalt in Enraged: Why Violent Times Need Ancient Greek Myths. The Iliad and masterworks by Euripides (Hecuba) and Sophocles (Ajax) show us, as they showed the ancients, that violent rage consumes perpetrator as well as victim—empathy, compassion and debate are the best defence against tyranny, in ourselves as well as others. That advice might indicate that the mass of Trump texts should simply be pushed off the bedside reading table, but even so, there are two 2019 titles that may still intrigue.

Former FBI deputy director Andrew McCabe, fired from his job 26 hours before his scheduled retirement, offers an impassioned polemic in The Threat: How the FBI Protects America in the Age of Terror and Trump, the subtitle of which lays out an eye-popping equivalency for an FBI man. McCabe details 20 years of major investigations in which he played significant roles, including the Boston Marathon bombing, before turning his attention to what he now believes is the greatest threat to his country: the Trump administration’s undermining of the U.S. constitution. And Chris Christie, former governor of New Jersey and Republican presidential candidate, who spent much of 2016 kowtowing to and being humiliated by Trump, seems to have devoted the years since to drafting his riposte. According to his publishers, Christie’s memoir, Let Me Finish—to which they have attached a here’s-what-you-get subtitle: Trump, the Kushners, Bannon, New Jersey and the Power of In-Your-Face Politics—will offer “newsmaking revelations” about his time at the court of the president-elect, including a detailed sketch of Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, “who never forgot that Christie was the prosecutor who put his wealthy father behind bars.”

Trump has no overt presence in The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives. But the compulsive tweeter comes constantly to mind as French sociologist Jen Schradie persuasively argues her counterintuitive case: digital organizing—once complacently thought by progressives to advantage their grassroots uprisings—has turned out to be another “weapon in the arsenal of the powerful.” Trump hovers, too, over Turkish novelist and journalist Ece Temelkuran’s How to Lose a Country: The Seven Warning Signs of Rising Populism. (Among those signs: “The infantilization of language and debate” and “underestimating your opponent.”) It’s an urgent call, issued as her own country is held ever tighter in the grip of authoritarian president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for the rest of us to disabuse ourselves of the idea that “it can’t happen here.”

The medium-term future, on the other hand, is looking good, according to Canadians Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson. In Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline, they argue a steep drop-off is already in progress everywhere. The eventual results will be beneficial, especially for the creatures that have to share the planet with humans, but also in higher wages, less hunger and tens of millions of empowered women. But first we have to get through the uneven transition process, where aging populations in the developed world have led to soaring health care costs and worker shortages while the remedy—increased immigration—has sparked nativism. That new world, happy or not, will see its centre of gravity shift eastward, writes Indian-American entrepreneur and speaker Parag Khanna in The Future Is Asian. Affluence and technological prowess are steadily catching up to population, and the continent that is home to more than half of humanity will soon dominate the globe.

Moving from macro to micro, non-fiction is as crowded with memoirs as ever, and 2019 has two Canadian standouts. In the memorably titled A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, the gifted Tuscarora writer Alicia Elliott, from the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve in Ontario, powerfully links larger questions of Indigenous life in North America—from the residential school legacy to the loss of native tongues—to the unfolding of her own life. And Hungarian-born Timea Nagy was a 20-year-old in Budapest looking for child care work in Canada in 1990 when she was lured by sex traffickers into forced prostitution in Toronto. Out of the Shadows tells the story of her ordeal, her harrowing escape after three months and her decades of activism for other enslaved women. The big picture impresses on us only so much. The stories that resonate the most are individual tales—redemptive or tragic or an all-too-human mix—the kind both Elliott and Nagy deliver.