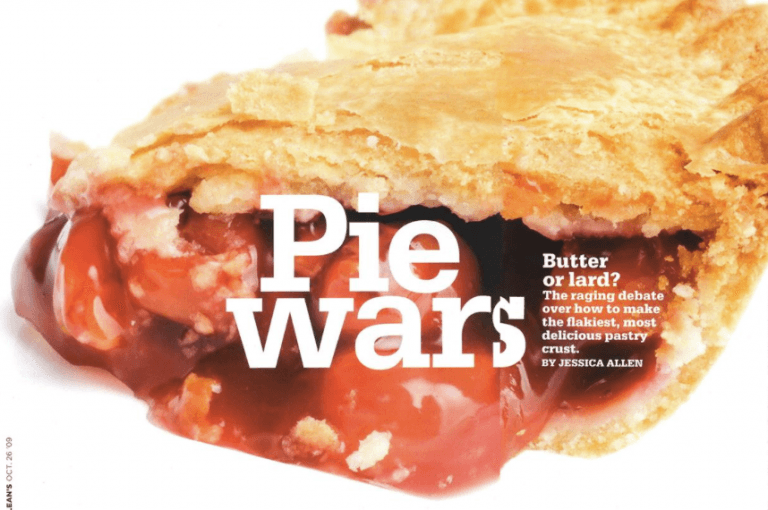

Pie wars

From 2009: Butter or lard? The raging debate over how to make the flakiest, most delicious pastry crust.

Share

This autumn hundreds, maybe thousands, of fruit-filled, double-crust pies—the sort grandma use to make two or three of at a time—will be entered into pie baking contests across the country. The recipes, often fiercely guarded relics passed down on stained five-by-seven-inch index cards, will vary endlessly. Some will call for specific fruit combinations or grinds of flour, while others will detail particular methodologies. But you’re bound to find one common denominator: these golden crusts will be crafted by home bakers using lard or vegetable shortening, rather than butter, which is the choice of many professional pastry chefs and domestic goddesses like Martha Stewart.

The pros argue that an all-butter wins on taste, and they may be right. But will the crust be as tender and flaky? Every pie eater has an opinion (sorry Martha; I’ll take Aunt Ruthie’s Crisco crust over your classic French pâte brisée any day). And so, too, does every baker.

Norma McCleary chooses lard—that is, rendered pork fat. She’s been baking pies for 65 years and has won more awards at the 30-year-old Perfect Pie Contest in Warkworth, Ont., than anybody else. If that doesn’t convince you of her pie making prowess, maybe this will: McLeary’s licence plate reads “MYPIE1.” “My two girls bought it,” she says. “And everybody always knows where I am.” McCleary, 84, isn’t baking as many pies as usual—just four or six a week for her church. “I had heart surgery so I kind of slowed up a bit.”

Janet Graham, from Bristol, Que., whose pie placed first this year at the apple pie contest at Ottawa’s SuperEX, also prefers lard. “The recipe I use is a family recipe. It’s my grandmother’s and she taught me how to make pies, and she always used lard so I always use lard.” Graham’s been making pies for 50 years. “Actually,” she told Maclean’s recently, “this afternoon I’m making more pies because I have another festival to enter.” When we called Susanne Mauer, who baked the first-place pie last year at the Rosy Rhubarb Festival in Shedden, Ont., she was just about to start making pies too. “I’m going to make about 18 lb. of lard into pastry,” she confessed. That answers that.

But vegetable shortening has its champions among prize-winning pie bakers, too. “I use Fluffo and I use Crisco,” says Lilias McKillop, 75, from Wallacetown, Ont. “Either one. Whichever is the best price.” McKillop won first place this year at the Rosy Rhubarb Festival. And although her mother didn’t bake, her mother-in-law did: “She was a very, very fine baker and she used shortening.” McKillop, who was born in Glasgow and sounds like a real-life version of Mrs. Doubtfire, only sweeter, has never attempted an all-butter crust. “But before I put the top crust on,” she says, “I put a few wee knobs in there for flavour.”

In fact, none of the 10 pie-baking festival winners with whom Maclean’s spoke has ever made a pie crust from 100 per cent butter. But Dufflet Rosenberg, owner of Dufflet bakery in Toronto, has. She always uses all butter for her seasonal pies. “Now, you’ll never get it as flaky as a shortening or lard crust, but people won’t leave the crust on the plate and pick out the filling,” says Rosenberg. “They’ll actually eat it because it tastes good.”

Rosenberg may be on to something: it turns out there’s a little science behind the art of making pie crust, and it sheds some light on why so many home bakers use shortening (made from vegetable oils such as soybean and cottonseed) or lard. Harold McGee, author of On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, helps explain. Butter is unforgiving, he says, because it has a lower melting point than the other two fats. That means you have to work fast while mixing it into the flour and rolling out your dough in order to keep it cold. Lard and vegetable shortening have higher melting points, making them easier to handle, which often results in producing a flakier texture. And to boot, vegetable shortening and lard are often cheaper than butter—a very practical consideration for home bakers who might make several pies in a week.

Butter, though, McGee admits, tastes the best. Elizabeth Baird, food editor of Canadian Living, agrees. “All-butter pastries won’t have the same flakiness,” she says, “but they’ll have a lovely taste.” Baird is also a former judge at Warkworth’s perfect pie contest. “All the women there, and all the winners, seem to be united in their devotion to lard.” And she admits, “They were always the best pie crusts.” Regardless, Baird falls into the all-butter camp, too, “or sometimes butter with a bit of lard.” And she’s against vegetable shortening—“because it’s made up of trans fat.”

On the health front, all three fats are, well, fat. Butter is between 80 and 85 per cent fat (the rest is water, which contributes to its finicky baking nature), while both lard and shortening weigh in at 100 per cent. And while shortening, originally a crystallized cottonseed oil invented in 1911 by Procter & Gamble as a cheap substance for making candles, isn’t exactly appetizing, it’s not as bad as gourmands make it out to be: according to the Canadian nutritional labels on some of the most popular brands, shortening contains less saturated fat (bad fat) than both butter and lard. All three contain trans fat—shortening has the most and lard the least—but the trans fats in shortening are a result of being partially hydrogenated, a process that takes a liquid and turns it into a solid at room temperature, while those in butter and lard occur naturally. Commercial lards like Tenderflake now tout trans-fat-free products, which makes one wonder how in fact they removed them, if they were there naturally to begin with.

In any case, the Food Network’s Chef at Home star, Michael Smith, says he prefers butter: “I would rather my fat be Mother Nature’s fat than a factory’s fat, so I fall on the side of butter.” Smith doesn’t believe “that the crisp crust prerogative outweighs the health prerogative. So I simply can’t advocate lard and absolutely under no circumstances vegetable shortening.” But he admits, “If anybody’s telling you lard makes the best pie, they’re right. Shortening is a close second in terms of crispness.”

There is an option that doesn’t sacrifice the melt-in-your-mouth crumbliness of a great pie crust for the delicate flavour of butter: combining fats, and it’s the choice of bakers like award-winning food writer Marion Kane. Although she very often uses all butter for her crusts, Kane’s ideal combination is butter and lard: “If I was given my druthers, and I wasn’t serving it to vegetarians, I would use half butter and half lard. To me, that’s the ideal combination because butter gives the taste and lard gives the texture. There’s no two ways about it.”

The compromise doesn’t convince all professional chefs: “Personally, I am a child of Julia and I am an all-butter girl,” says Food Network star Anna Olson, although she does admit there is a time and a place for both lard and vegetable shortening. But Julia Child herself falls into the combo-fat category. In Mastering the Art of French Cooking, she recommends combining butter with vegetable shortening. “Butter gives the pastry its flavour and texture,” she writes, while vegetable shortening “has a tenderizing effect that almost all American flours seem to need.”

Wanda Beaver agrees. Her bakery, Wanda’s Pie in the Sky in Toronto’s Kensington Market, uses a combination of butter and a non-hydrogenated shortening. “The idea of pig fat with a dessert doesn’t appeal to me,” she says. But Beaver admits, “your grandmother or your great-grandmother will swear by it for making pies.”

It may only be flour, fat and water, but pie crust is complicated. As Olson says, “It’s so particular to the self. I judged an apple pie contest a couple of years ago and we had over 60 entrants and each pie tasted distinctly different.” Or maybe, as Smith says, “we’re splitting hairs. The difference between the crispness [of these pies] is minimal at best. I mean, you’d have to be judged in a contest before somebody would really notice.”