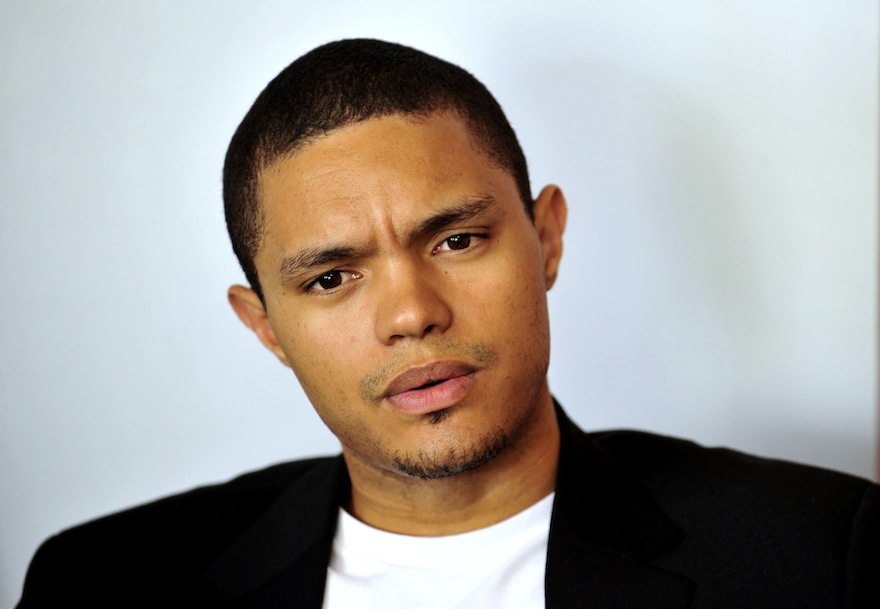

Trevor Noah and the search for the perfect joke

The new host of the Daily Show is in hot water over some offensive—mostly bad—jokes. Jaime Weinman on his discomfort with our ‘rule of funny’

Share

I was asked if I wanted to say something about Trevor Noah’s old tweets and the lessons we should learn thereby and therefrom. While these tweets are of course Extremely Problematic, I don’t think they’ll stop him from becoming the host of The Daily Show, though they do emphasize further that this guy was not their first choice. What is interesting, apart from the usual arguments about “outrage culture” and which of his tweets are actually offensive (I saw one argument in a blog comments section about which of his tweets are anti-Semitic, which is bad, and which are merely anti-Israel, which is good), is that so many of the responses to these jokes emphasize the idea that they could be acceptable if only they were funnier.

A ritual of talking about the problem with Noah’s jokes about Jews, “fat chicks” and other old comedy targets is to say that it’s okay to make a joke about anything, the problem is that these jokes are not funny. Then we get an explanation of why they’re not funny: usually because they Punch Down, or attempt to cater to the audience’s prejudices instead of enlightening us. Here’s a classic one from Vox, the site that has made a niche for itself by explaining to us why we are good people for being offended by things:

Still, these jokes are offensive because they are reflections of cultures that are oppressive and privileged — and rather than being critical of those societal constructions, the jokes instead reinforce them.

Or this one, from Slate, headlined “The Problem Isn’t That Trevor Noah Is Offensive. The Problem Is That He’s a Giant Dope.”

The problem is not that Trevor Noah tells offensive jokes. It’s not even that he routinely breaks The Daily Show’s covenant of speaking truth to power in favor of speaking truth to fat chicks or Thai hookers or, as the Washington Post’s Wendy Todd points out, black Americans who give their kids names that Noah disapproves of. The problem is that Noah’s jokes are so annihilatingly stupid.

Well, I don’t think the jokes were funny either, though I don’t expect much more of something a guy writes on Twitter for free. Lena Dunham’s stereotype-filled “Dog or Jewish boyfriend?” piece wasn’t very funny either, and she got paid for it. (I didn’t find the piece offensive, mind you. As a Jew, I think both Noah and Dunham may have gotten a bit extra scrutiny because of the renewed fears of anti-Semitism, which leads to more scrutiny of Jewish stereotypes that weren’t as heavily scrutinized a few years ago.) But I’m still uncomfortable with the idea that the “rule of funny” means anything is acceptable if it’s funny, and conversely, that the real problem with an offensive joke is that it’s aesthetically bad.

There are many taboos in our culture, and one of those taboos is against appearing to be priggish or censorious, which means that we can never admit to criticizing a joke because it’s offensive, or because some subjects simply shouldn’t be joked about. Instead, we say, we are not offended — indeed, we want everything to be fair game for comedy — but it must be the right kind of joke. The problem isn’t with jokes about these subjects, but that they must illuminate and “punch up,” rather than being corny and stupid.

This is the part that I don’t like, more than comedians being criticized for their Twitter jokes. I mean, nobody likes being shamed for things they wrote years ago, but when you say stuff in public, you don’t have a right to be shielded from criticism. But the idea that there is some kind of platonic ideal of a “good” joke out there, or that jokes about Jews and fat people are OK if they’re adjudged to be the “right kind” of jokes, bothers me more than just saying some things should be off-limits. (Some things are always off-limits, and every artist in history has lived with at least some kind of censorship or self-censorship. I don’t think we need to scream at the idea that there are some subjects you just should stay away from or at least be really careful with.) Because let’s face it, most jokes are corny and stupid. And on paper—or on Twitter—there is virtually no difference between a “good” joke and a “bad” joke. They all have the same structure, rhythm and basic built-in assumptions. And any joke that hopes to make people laugh must incorporate some degree of stereotyping, because generalizations and the shock of recognition—of hearing what we already know to be true from our own observation—is part of the way jokes are built.

Usually when we get examples of non-problematic jokes, they’re Jon Stewart or Louis CK or someone like that abandoning jokes for a moment to get political or talk about the need to challenge stereotypes, which usually results in what has been dubbed “clapter”—the audience applauds because its beliefs have been flattered, or the comedian has brought up what the audience wants to believe, whereas the biggest laughter often comes from the affirmation of what the audience really believes. (Which is often stereotypical or somehow taboo; that’s why comedians often claim that their tasteless jokes are merely exposing the dark underbelly of what their audience believes, challenging us by bringing us face-to-face with our prejudices. This may be a self-serving and wrongheaded claim, but at the very least, you can’t assume that challenging a stereotype is more challenging for the audience than diving right into it.)

Related: Do stand-up comedians have it worse?

But more importantly, whether a joke is “good” or “bad,” or “funny” or “unfunny,” is so subjective as to be a useless criterion. It leads to us analyzing 140-character punchlines to explain why this one is okay, why this one is not, and why that one could be funny if only we changed a couple of words. And of course it leads to lots of circular arguments, with one person saying “I laughed! it’s funny!” and the other person saying it doesn’t matter whether you laughed, it’s whether the subject of the joke would laugh, and then we get into “I’m [fill in group] and I thought it was funny,” and so on and so on. All very unhelpful because there is just no way to define what a good joke is. For a comedian, the definition is simple: a good joke is a joke that gets a laugh from the paying audience. For the rest of us, we’re better off sticking with hard, unfunny facts, like what the joke is about and what stereotypes it’s peddling. There have been funny blackface scenes; that doesn’t mean blackface is OK if it gets a laugh.

The problem with the Search For the Good Offensive Joke is it turns us all into the unfunniest things in the world: analysts of comedy, parsers of jokes. I would much rather be a censor or a prig than a parser; if it weren’t for people like us trying to define what subjects are okay and which are not, who would comedians have to rant against? And more importantly, I’m qualified to be a censor or a prig, much more than I am to tell a comedian how to write jokes. There are no professional requirements for pointing out what’s offensive; I can do it, anyone can do it, and do it well. We’re all qualified to tell Trevor Noah that his jokes are wrong or offensive. If we start telling him how to do his job, well, we’re probably going to lose that argument.