This is not what Jason Kenney came back for

He returned from Ottawa with a suitcase full of ideas about who Albertans are and what they want from their premier. How a seemingly perfect political match went wrong.

Premier Kenney in April 2020. (Courtesy of the Government of Alberta)

Share

Jason Kenney had a series of ambitions for himself and Alberta when he began, five years ago, on a quest to restore the province. He’d become the Alberta conservative movement’s leader, merge two right-leaning parties into one and topple Rachel Notley’s NDP government, which slid almost instantly into unpopularity as the oil sector dragged the province into recession. He’d been a Calgary MP for 18 years, though he’d spend only a few days per month in Alberta due to his Ottawa cabinet work and politicking for the Harper Conservatives in immigrant-heavy swing ridings. Ontario-born and Saskatchewan-raised, he’d lived in Edmonton full-time in the mid-1990s while leading a taxpayer’s advocacy group. So this was a homecoming of sorts. There was attitudinal alignment out west: Alberta clearly skewed more conservative than most of Canada, and so did Jason Kenney.

His promises stayed consistent: resurrect the “Alberta advantage” when it came to the economy; bring back the budget-balancing fearlessness of former premier Ralph Klein; and use government muscle to boost the energy sector’s reputation and might. He bombed around the province in a blue pickup truck and told supporters at rallies: “We get ‘er done.” The formula appeared to work, at least electorally. The province may have become more diverse and urban over 20 years, Kenney told Maclean’s during his long campaign, but “the thing I find is that Alberta is still Alberta.”

Nearly two years into Kenney’s stint as Alberta premier, nothing is what it seemed. The disorientation runs deeper than the common, pandemic-induced challenges and public malaise that has undone the political agendas of leaders around the world; deeper even than the profound hardship and unemployment inflicted by the downturn of the energy economy. Albertans are coming to realize they’re in the midst of a deeper, structural change, not another bust to be succeeded by another boom. Kenney has taken halting steps toward that new era. But he’s largely stuck with his pre-pandemic agenda—drawing outcry from Albertans angry about cuts to the public sector or government spending on private interests.

The blowback has come not only from progressive opponents ticked with, say, Kenney’s push to curb doctors’ pay and close provincial parks; or with his libertarian reluctance to enact health restrictions as coronavirus hospitalizations rates spiked. It’s coming from within the conservative coalition he knit together, which is increasingly disillusioned and now risks unravelling. Many rural Albertans who supported him are frustrated both by things Kenney has done—such as his partial COVID lockdowns, which some of his own MLAs now openly criticize; and things he hasn’t, like translating his anti-Ottawa rhetoric into action. “There’s no base right now for this government to hold on to because they have just been agitated in all the different little ways,” says one United Conservative government source who didn’t want to be named.

Kenney turned the page on 2020 with an even rougher January, when one-tenth of his caucus was caught holidaying abroad despite travel advisories and lockdowns. The premier sanctioned a minister and his chief of staff, but only after his lenient response was universally condemned. He’d badly misread the popular mood, and not for the first time since he won election with what once seemed a perfectly calibrated message.

More signs of this disconnect emerged after the travel fiasco. His government’s bid to expand coal mining in the Rockies drew backlash from quarters ranging from ranchers to small-town councils to Paul Brandt, the country singer whose tune Kenney had used as a campaign theme song. “Kenney’s been dwindling since day one,” says Craig Snodgrass, a vocal critic of the coal plan and mayor of the reliably conservative southern town of High River. “He knows exactly what strings to pull with people to get elected. That only lasts about six seconds after you’re elected. Now you’re the guy, and you’d better have your sh– together. And he does not.”

***

This is not the Alberta that Jason Kenney came back for—it’s different in outlook, and in its reception to the Great Right Hope he presented himself as. He has time in his mandate to figure out what Albertans want, but a track record with so many missteps leaves him with so much more to fix.

He’d promised Albertans plenty—375 specific commitments in his platform that he made much of during the election campaign, from ending renewable energy subsidies cutting red tape to requiring all universities to adopt free-expression policies. The overarching—though unspoken—proposition: a new era of political stability, again hearkening back to Klein, the four-term Tory premier of the ‘90s and early 2000s.

There had been 12 premiers in the province’s 101-year history when Klein resigned in 2006. Alberta has had six in the 15 years since, thanks to both conservative infighting and public dissatisfaction. No premier in that span won two straight general elections, all of which has turned Canada’s most politically staid province into its most turbulent. Kenney, with his political savvy as Harper’s lieutenant, was expected to usher in a renewed period of Conservative dominance and reliability. He made serious headway by winning nearly three-quarters of Alberta’s seats in the 2019 election and more votes than the former Wildrose and Tory parties combined. It was better than most polls predicted.

“This is not the Alberta that Jason Kenney came back for”

But the hostility Kenney faced for the snowbird scandal, and his uneven COVID response, show that instability is taking no holiday. His approval ratings are in the tank, and several recent surveys put his party behind the NDP. One lobbyist tells Maclean’s he’s lately advised clients to keep in touch with Notley’s opposition party, too, hedging against a future change in government. “We’ve been hard on each and every premier that has come through,” says Maryann Chichak, a longtime Conservative activist and mayor of the town of Whitecourt. Not long ago, she says, Albertans were more forgiving of mistakes on the part of Klein or Peter Lougheed. But not long ago, Chichak observes, Albertans were “content and comfortable.”

Why should Alberta be politically stable, in a fundamentally destabilizing period? The oil industry, still recovering from a price collapse last decade, was clobbered anew in 2020 by a global supply glut, a demand plunge caused by a halt to international travel and commuting, and growing concern about climate change among global policymakers and financiers (Kenney had dismissed that as “flavour of the day”).

The province went into the pandemic with Canada’s fourth-highest unemployment rate; by December—even though it had shut down fewer workplaces than other provinces—Alberta had the second-highest, at 11 per cent, behind only Newfoundland and Labrador. There are nearly five Alberta job seekers for every vacancy, according to analysis by University of Waterloo economist Michael Skuterud.

Parents are increasingly unsure if university-age kids can find futures in the province—a reversal from decades when it was a magnet drawing enterprising young Canadians from elsewhere. After having the highest proportion of residents in the 20-24 age demographic in 2010, Alberta was seventh on that score by 2019, Statistics Canada estimates show. Jim Gray, a seven-decade oil executive who experienced both sides of several V- and U-shaped economic downturns, says this feels more like a L-shaped slump, and that Alberta faces a new normal. “We’ve built a wonderful society on a very narrow base. That’s changing, and it isn’t very easy to adapt to that change, Gray says.

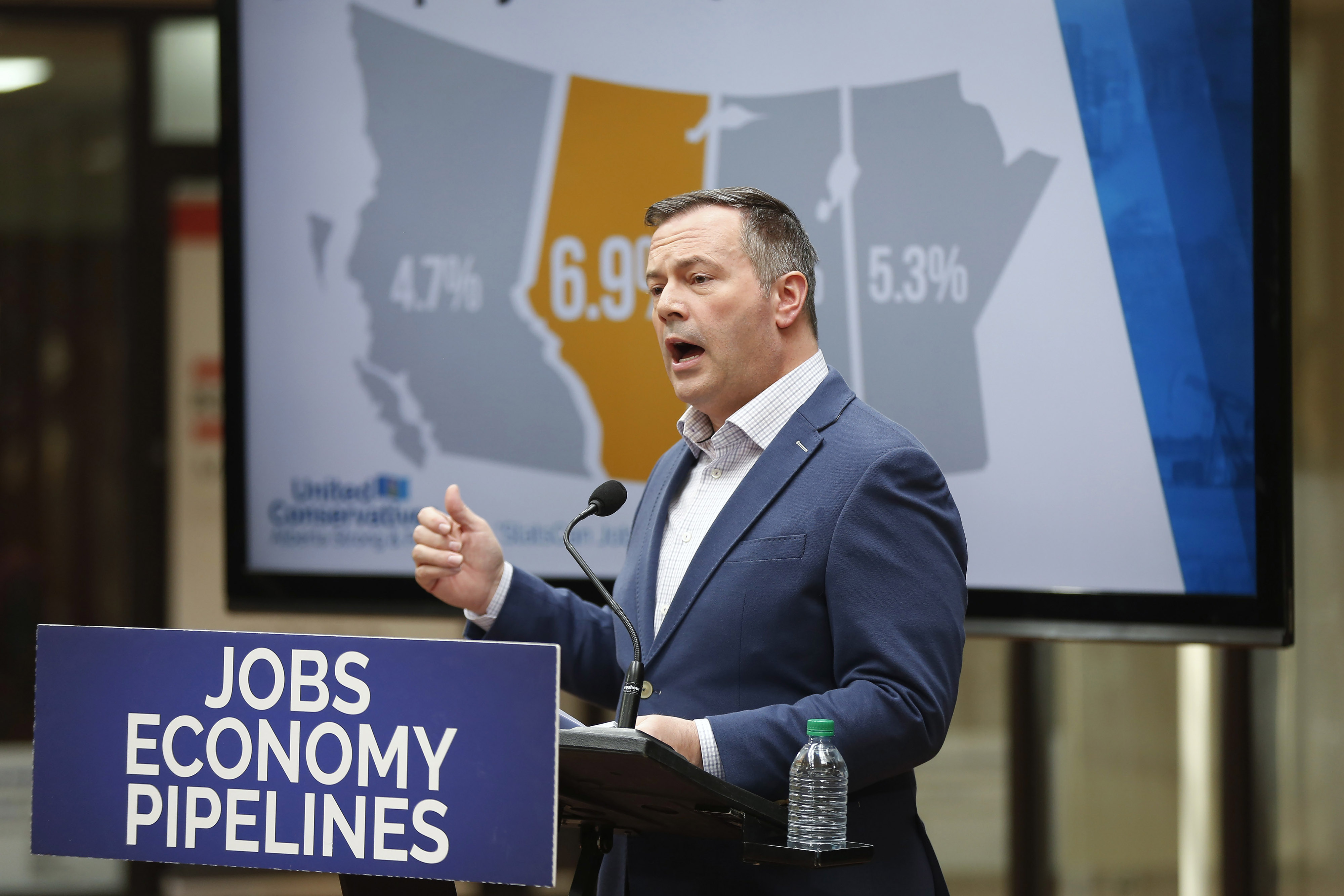

Kenney speaks during a news conference in Calgary on April 5, 2019. He said he would create a $1 billion crown corporation to support Indigenous resource projects including pipelines if he's elected to lead Alberta's government. (Todd Korol/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

***

Whereas Kenney campaigned that “hope is on the horizon,” a sense of resignation is settling in. More than half of Albertans now feel its best days are behind it, according to opinion research by the academic Viewpoint Alberta project. Not long ago, there remained a sense that the province was still ahead, that it was merely being held back by outside forces, namely: an unappreciative central government that premiers have long railed against. “Now there’s a feeling like Alberta is falling behind the rest of Canada, and that is a very different position for a premier to lead,” says Jared Wesley, a University of Alberta political scientist and Viewpoint’s project leader. (Kenney’s office declined an interview request from Maclean’s, and also did not provide answers to a set of written questions a spokeswoman had invited. There was also no reply to a request to the minister of jobs, economy and innovation.)

Kenney had brought hope of robust, back-to-basics recovery with his 2019 promises. Cut taxes, axe regulations, and use government muscle to defend the energy sector. It resonated. “I don’t think Albertans wanted to pivot hard right—it was a wistful longing for when things were stable and the oil economy was going well and lots of people had jobs,” says Emma May, who was an aide to former premier Jim Prentice. Kenney’s simple campaign slogan: “jobs, economy, pipelines.”

There is little good news to point to on the first two scores, and Joe Biden’s cancellation of the Keystone XL permit was a major blow on the third. It left Kenney holding the bag on more than $1 billion in investments and guarantees he’d sunk into that project—the sort of gamble with taxpayer dollars he used to mock “as politicians risking your money.” But he swore it was necessary to prevent Keystone’s premature demise.

His other bids to support the oil patch, a $30-million-per-year energy information “war room” and a public inquiry into foreign-funded oil sands opposition, have generated little more than embarrassing headlines that trade on stereotypes about Alberta’s environmental irresponsibility. Meanwhile, many oil companies themselves are adopting net-zero carbon goals. California, Quebec and even General Motors have pledged to stop sales of new fossil-fuel combustion vehicles by 2035.

Kenney has made some nods towards economic diversification, pledging in last summer’s recovery plan to outline industrial strategies for a variety of sectors. That includes some new tech incentives after he’d axed several of the NDP’s a year earlier. The Trudeau government, which Kenney’s team often maligns, has become a close ally on oil-well cleanup, along with hydrogen and geothermal energy initiatives. Kenney put much stock into accelerating his corporate tax cut, even suggesting it could lure a big eastern financial firm, though none has moved yet. Major banks say Alberta led the country in economic decline last year, and predict its recovery will only be middle-of-the-pack in 2021 and 2022.

There’s hunger, meanwhile, for more serious soul-searching—especially in Calgary, where nearly one-third of downtown office space sits vacant. Notley has launched consultations to set out a long-range vision for Alberta’s future. “Slowly over the last six or seven years, Albertans have been coming to terms with the fact that there’s no simple, fast magical solution,” says the former premier, who stayed on as NDP opposition leader. May, the former Prentice aide, has formed a non-partisan policy panel called the Next 30. Gray is among the oilmen now dabbling in tech venture capital, and he looks to Kitchener-Waterloo’s tech renaissance as a model for his oil city. “They reinvented themselves, and that’s what Calgary has to do,” Gray says. “Calgary’s capable of moving with (the changing world), but we mustn’t say let’s just hang this out, we’re going back to the good old days. We’re not going back.”

A tanker truck trailer in a field along the Keystone XL pipeline route near Oyen, Alberta on Jan. 27, 2021. U.S. President Joe Biden revoked the permit for TC Energy Corp.'s Keystone XL energy pipeline via executive order hours after his inauguration. (Jason Franson/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

***

In the name of “economic recovery and revitalization,” Kenney’s government announced in May it would scrap a 1976 policy that protected areas in the Rocky Mountains and their foothills from open-pit coal mining. Opposition began gradually, with academics and First Nations worried about watershed impact. Then, nearby ranchers on the southern Rockies’ slopes got on board. By January, southern municipalities and country singer Corb Lund began fighting it. So did Brandt, whose heart-tugging anthem “Alberta Bound” Kenney had used during the campaign.

“We can’t put short-sighted economic benefit ahead of long-term consequences that could devastate our people and land for generations to come,” Brandt said on Facebook, next to a picture of him fly-fishing in an Alberta stream. Four days later, the Kenney government partially retreated, saying it would cancel 11 recently issued coal leases and pause future sales in the once-protected lands.

Snodgrass, the High River mayor, told a podcaster Kenney was “full of sh–” and was elected on “false promises.” The premier, he said, has “had no success getting the energy industry going … and when you’re desperate, when you’re backed in a corner, you start making mistakes.” High River lies in a riding where the UCP won 71 per cent of votes. Yet Snodgrass says the public feedback to his remarks was 100-to-1 positive. And by early February, the government had waved the white flag, reinstating the coal policy. “We’re not perfect, and Albertans sure let us know that,” Energy Minister Sonya Savage told a news conference, pledging to consult on any future changes.

Sure, Conservatives could point out that British Columbia has been actively expanding its mountainside pit mining. But Kenney’s bid to open more of Alberta’s slopes to resource exploitation reveals his misunderstanding about what Albertans cherish—moreso, even, than economic growth. The same tin ear was apparent when the UCP sought to trim the parks budget by closing or ceding provincial control of 164 “underutilized” park and wilderness sites.

This proved a political third rail, as almost anyone who escapes from the province’s cities on weekends might testify. The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society made 1,000 “Defend our Parks” lawn signs for inner-city Calgarians, but demand across Alberta grew to about 20,000, one of the biggest sign campaigns in recent memory. “You don’t mess with parks in Alberta, and this government just didn’t get the memo on that,” says Katie Morrison of CPAWS. Kenney’s team ultimately did: in December, it backtracked and pledged not to delist any parks.

In recent months, Kenney has lost many of his top aides—including his chief of staff, pushed out after travelling to Britain in December—and there’s been ongoing concern he imported too many of those around him from Ottawa or from other provinces. “Too many people working for you have moved here to work for a stereotypical Alberta that only exists in their heads,” former Wildrose party leader Brian Jean wrote in an Edmonton Sun op-ed addressed to the premier. (As some novices and outsiders move on, Edmonton legislature offices have been quietly restocking with veteran aides of Alberta Tory yesteryear.)

“On managing that pandemic, Kenney has also received poor grades”

Kenney’s recent ping-ponging from controversy to controversy is partly due to his obstinacy amid the pandemic. As case-counts and deaths mounted, no other Canadian jurisdiction so assertively raced along on other policy fronts like Alberta and its checklist-obsessed premier. That has led the UCP into a very public contract war with doctors in the middle of a public health emergency—a potential preview of bitter pay disputes the government has hinted at with other public-sector groups vital to pandemic recovery, like nurses and teachers.

Kenney had pledged tough decisions to rescue Alberta from a $7-billion yearly fiscal hole, before COVID and other crises pushed the deficit to triple that level. A collapse in oil royalties and tax revenue has deepened the government’s conviction it has a spending problem; fixing the tax-income side of the ledger is a maybe-next-time problem. The approach does reflect the Albertan ethos that governments must live within their means. But there’s a powerful countervailing force: Albertans are used to the top-flight services that oil wealth used to provide, and damned if they’ll surrender much of it.

Kenney tried to explain away the end of cost-of-living increase to those on severe disability benefits, and a review of eligibility criteria. But even UCP MLAs stress under the steady outcry from recipients and their families—a repeat of withering backlash past Conservative governments faced when trying to tighten up disability benefits—though Kenney wasn’t around for those episodes.

And while some in the base may applaud spending restraint, a public wracked with unemployment and reduced incomes seems ill-disposed toward further austerity. “He was the right leader in the minds of many Albertans to carry us through the fiscal reckoning that he promised,” Wesley says. “But we’re not there anymore. We’re in the midst of a pandemic instead.”

***

On managing that pandemic, Kenney has also received poor grades. Some of that may have to do with the cerebral leader’s preference for explaining things rather than empathizing with an anxious public—a tendency even supporters quietly acknowledge. Some may have to do with his insistence on plowing through the rest of his agenda, which in turn has licensed the NDP to keep up the bitter partisanship. Unlike oppositions in other provinces, the New Democrats have cut the governing party little slack in the name of pandemic unity.

Then there was Kenney’s handling of the fall second wave, as Alberta watched COVID cases and hospitalizations tick up at an almost unequalled pace, while the premier insisted that trusting “personal responsibility” was better than the “indiscriminate damage” of spread-limiting restrictions. Finally in December—as the medical system reached a breaking point and field hospitals were in the works—Kenney relented and shut all dine-in restaurant service, salons and gyms. In doing so, he made a great show of contrition to the business owners affected. To critics who pleaded for the same actions several weeks and hundreds of sickened Albertans earlier, he offered no regrets.

Wayne Smith and his grandson Matthew Lo, 10, enjoy dining in at Hunter's Country Kitchen, as Alberta begins Step 1 of a plan to ease restrictions, in Carstairs, Alta., Feb. 8, 2021. (Jeff McIntosh/CP)

In January, Kenney admitted internal public polling suggested that about 40 per cent of Albertans had found the province’s health restrictions to be insufficiently strict. About the same proportion said they were well-balanced, while a mere one-fifth found them to be overkill. He revealed the numbers on the same day in late January that he announced a phased reopening of restaurants and gyms, while three things were happening: COVID hospitalizations had steadily dropped, more infectious new variants were cropping up in Alberta, and several small-town restaurants were already reopening in defiance of provincial orders. At the same news conference, the premier scolded those business owners for “thumbing their noses at the ICU nurses,” while informing them they could legally resume table service in about a week.

The province’s options, on COVID and so much else, range from tough to brutal, Kenney says. “Often we only have poor choices to make, but there is no easy way through this pandemic,” he told reporters at a Feb. 3 briefing. “There is no easy way through a global recession and a massive collapse in energy prices. Frankly there is only a hard way through it.”

It’s been enough to tick off nearly everyone. The latest Leger survey says that 72 per cent of Albertans are dissatisfied with their provincial government’s handling of the pandemic, far worse than any other province. Of the remainder, a dismal four per cent say they’re “very satisfied.” In other words, it’s easier to find Albertans who think the Keystone XL cancellation was a good thing than to find ones saying they love what Kenney’s done on the COVID file.

Only a small segment of Alberta may agitate for looser restrictions, but that is Kenney’s segment of Alberta. The heavily rural Conservative base. It much prefers his appeals to freedom, jobs and personal responsibility. “They’re far more willing to have things open up than worry about the health consequences,” says William Stevenson, a small-town accountant in Carstairs, and former UCP treasurer. In February, two backbench government MLAs defied Kenney by publicly joining an “end the lockdown” group. When Ontario Premier Doug Ford was faced with a member publicly criticizing restrictions, he promptly turfed the MPP from caucus for undermining health advice. Kenney, normally a heavily controlling leader, said he’ll tolerate a range of expressed views in his ranks.

The restoration of personal-trainer sessions and 10 p.m. last calls at the bar seems unlikely to mollify these Albertans. Yes, they were the ones who chafed hardest against lockdowns and restrictions. But they were also the ones who felt most betrayed to learn a cabinet minister, five backbenchers and some government aides had jetted off on Christmas vacations. They were no more pleased with Kenney, when his initial response was to publicly praise safe travel and urge support of Calgary-based WestJet rather than sanction those who ignored stay-home advice (that came via Facebook post three days later). He didn’t appreciate the anger fellow Conservatives felt, some supporters say.

These are also the voters who want him to move more quickly on Alberta-first, anti-Ottawa actions with which he has long tantalized his Trudeau-loathing base. His offerings include a referendum demanding equalization reform, and proposals to create Alberta’s own police force and pension plan—two pricey initiatives that find little favour except among ardent conservatives. But those conservatives truly lap them up. Expect him to find more red-meat morsels for his base this year, lest frustrated UCPers move to fledgling, quasi-separatist parties on the right, or reject him at a forthcoming leadership review. He can’t show them success on jobs, the economy or pipelines, so he has to do something.

“He’s got to have at least the appearance of listening to what the public wants, rather than just doing what he thinks is best,” Stevenson says. Such a disconnect, perceived or real, has proven the end of other premiers in Alberta’s last decade of political churn. One of the most politically experienced figures in Canadian leadership, Kenney has yet to prove he can rise to the demands of multi-crisis leadership, and his offerings of pre-crisis policy have been out of sync with public expectations in a new reality.

He does, however, have the benefit of time before Alberta’s 2023 election—time to figure out how to balance his rural base’s demands with those of urban moderates, and bring the economic revival he’d promised, and manage a structural fiscal crisis without alienating everyone who relies on public services and salaries, and figure out a way forward for the energy economy, either through transition or steely resilience.

When he set off on his complicated quest to swoop in and unite two warring conservative parties and lead this united group to victory, political watchers’ refrain was: if anybody can do it, Jason Kenney can. With problems all around him, who’s saying that now?