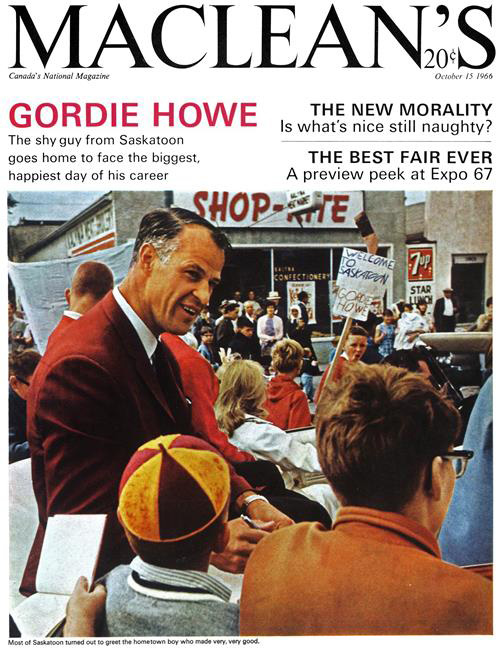

From the archives: Gordie’s return to Saskatoon in 1966

Saskatoon had never known a day like this, as 70,000 proud hometowners cheered the world’s greatest hockey player

Share

Hockey legend Gordie Howe passed away Friday at the age of 88. Howe was at the height of his fame when, in 1966, Saskatoon welcomed him back for its inaugural Gordie Howe Day. Maclean’s was there that autumn to witness his trip home.

They were all there, every marching band that mattered in Saskatoon—the Fireman’s Band, the Police Band, the Boys’ Pipe Band—all puckering for effect and exchanging cacophonous bleeps and blares as they primed their brasses and woodwinds for the big blow.

Equally resplendent, a block-long cavalcade ot sleek new convertibles was glittering in the sunshine, growling through chrome teeth at parade chairman All Bentley as he gave the order to start engines.

And in the last car, the profile was familiar, but Gordie Howe was not the burly imposing figure western TV hockey fans remember, but a fidgety father of four, rubbing his sweating palms together and making a brave attempt to engage in idle chitchat with his family — anything to help stem the mounting tension within him. All his adult life, he had earned a living performing under the critical scrutiny of thousands, but he could shut them out then, because he had been preoccupied with a stick and a puck. Now, just around the corner on this bright July morning, were 70,000 people — two thirds of the entire population of Saskatoon — waiting along the parade route to stand him the emotional binge of his life: Gordie Howe Day in his old hometown.

Sitting there, beside his attractive blond wife Colleen, Howe wore the expression of a nervous rookie about to take the ice for his first NHL game. He had confided to friends the night before that it was going to take all the stamina he could muster just to retain his composure throughout this day. Lavish tributes had always embarrassed him, and this mass eulogy was to last 14 hours. The parade was only the start.

The cavalcade was moving now, inching around the corner onto 21st Street, where the first phalanx of well-wishers were wedged tightly from curb to storefront, bobbing up and down for a better view, like so many tufts of prairie wheat.

Soon Gordie’s face began erupting in a succession of explosive grins as he swiveled to and fro to acknowledge the shouted greetings from people on both sides of the street. Periodically, his head would bow, and the corners of his mouth would sag, as if in sombre reflection of the old days. There were no convertibles to ride in then. He and his boyhood pal Mike Yano were lucky it they had bus fare. But they didn’t mind the subzero frost nipping at their ears and noses, or the squeaking snow underfoot, as they walked over to the Hudson Bay Slough on those winter afternoons. It had all started for Gordie that day a woman in a flimsy cloth coat stood on the frontdoor stoop of the Howe house on Avenue L North, her bare fingers wrapped around a huge gunnysack. It was December 1933, and she was shivering, but not from the cold. Mrs. Howe answered her knock immediately and invited her inside.

“Can you help me out?” the caller pleaded. “My husband and baby are both sick, and we have no milk. If you’ll give me a dollar, you can have everything in this sack.”

Without even glancing down, Mrs. Howe went to the kitchen, dipped a hand into the jar that held her milk money, returned to the door, and pressed $1.50 into the woman’s hand. When the woman was gone, Mrs. Howe took the sack and dumped its contents onto her linoleum floor. Among the items considered expendable for milk this day was a pair of skates. Five-year-old Gordie quickly grabbed one, and his older sister Edna eagerly pounced on the other.

The next day, hand in hand, the two youngsters set off to the rink, wearing one skate apiece — size six and far too big, with rags stuffed in the toes to make them fit.

A week later, Edna surrendered her skate to her little brother, and every night from then on he would stagger home from the rink for supper, tired and covered with snow from countless tumbles. But he was learning to skate.

And one day, young Gordie Howe would skate and play hockey better than anyone else in the world. In 20 record-smashing years with the Detroit Red Wings he would be 17 times a National League all-star; six times its most valuable player and scoring champion; and he would score more goals, earn more assists and play more games than any other player in NHL history.

His mother, Mrs. Catherine Howe, was tingling all over as she rode, quite erect, beside her husband Ab Howe in the car ahead of Gordie’s, and she glowed with pride as she saw and heard an entire city eulogizing her son. But more than pride was causing her to cherish this day. For the first time in 18 years all nine Howe children were together.

It was a rare occasion to reminisce about those days when Gordie was a mischievous little boy. When he was five years old, he used to scour the back lanes, looking for corn syrup labels in garbage tins. Then he’d get his sisters to send away for hockey pictures for him. “He was crazy about any picture or book on hockey,” his mother recalled. “He couldn’t read, but he’d thumb through them anyway.” And he was always asking her. “Can I be a hockey player some day? Can I, Mom?” When he was six or seven, he’d come home from school, and it was “C’mon, Mom, let’s play hockey.” Gordie would find her an old stick and they’d either play in the kitchen with old sealer tops, or go outside and shoot rocks against the shingled veranda.

As the parade was rolling past the halfway point on Second Avenue, one of the Howe youngsters made a face at a photographer and promptly received a cuff behind the ear from his dad. When he wasn’t exchanging hellos and salutes with the crowd, Gordie’s eyes flitted back and forth between huge placards, being hoisted by young children, emblazoned with slogans: “We love you. Gordie” … “Long live Gordie Howe” … “Even the Indians say Howe.”

The presence of so many youngsters seemed to relax him a little. After all, he wasn’t skating around now in front of millions of TV fans; he was just back home. And for all they cared, he could probably slip away later and take a few shots at the side of his old house if he wanted to. Ab Howe chuckled now when he thought of the beating those veranda shingles used to take. “The house wasn’t ours . . . and I was afraid we’d get kicked out. But every day, it was the same thing.” Ab played hockey himself — just pick-up-team stuff, married men against the single men back in Le Bret, Sask. “But I couldn’t shoot. Gordie didn’t get his hockey playing from me.”

In winter, Gordie would go down to the Hudson Bay Slough every weekend with a school chum named Frank Shedden, and they’d play hockey from morning until dusk. There’d be 30 or 40 boys on each side, and the final score would be something like 369 to 300. “There was no passing,” said Shedden. “You just tried to get the puck. And I seem to recall we spent most of the time chasing Gordie.”

Now the parade was over, and members of the cavalcade were gathering with civic officials at JD’s restaurant, where Ernie Cole, the mayor of Saskatoon, read an official proclamation declaring July 22 to be Gordie Howe Day, and provincial and federal delegates made presentations to the Howe family.

Gordie was feeling a bit jittery when he rose to make his first speech of the day. “I’d much rather be fishing than speaking here now,” he said. “I’ll be a nervous wreck by tonight. But this tops everything that ever happened to me . . . except my wedding. I gave Pierre Pilote [of the Chicago Black Hawks] a hug at the press reception last night, and he said to me, ‘Gord, I’ve been playing against you for 10 years and that’s the first time I’ve seen the inside of your elbow!’ ”

Gordie went on, telling the gathering how he lacked sufficient education to make a proper thank-you speech. That apologetic explanation seems to be almost a reflex action every time he steps onto a public platform, as if some youngster might get the impression that because Gordie Howe has only a grade-eight education, that’s enough for any aspiring hockey player. But Gordie doesn’t need to worry about not having his audience with him, because youngsters and grownups only want to hear him talk about hockey, a vocation in which he has earned a master’s degree. As a speaker, he has effectively developed a homespun delivery that generates warmth in any audience, mainly because he seldom strays from easily digestible anecdotes about hockey. Eaton’s has signed him to a 10-year contract to tour Canada each summer and make friends with sizable audiences. But his poised manner now is a radical departure from the way his brothers and sisters remember him as a boy.

“He used to be all arms and legs,” said his sister Gladys. One day she saw him walk by the living-room window on a pair of six-foot stilts. He fell on a neighbor’s fence post and ripped a big three-corner tear in his side. “Mom carried him into the house. He was bleeding terribly, but the doctor stitched him up, and he was off, out with the kids again.”

“I don’t know how he got anywhere being so shy and quiet,” said his sister Vi. But she could see it coming out in him then, the way he handled a hockey stick, as if it were part of his body. “Hockey seemed to be built right in him.”

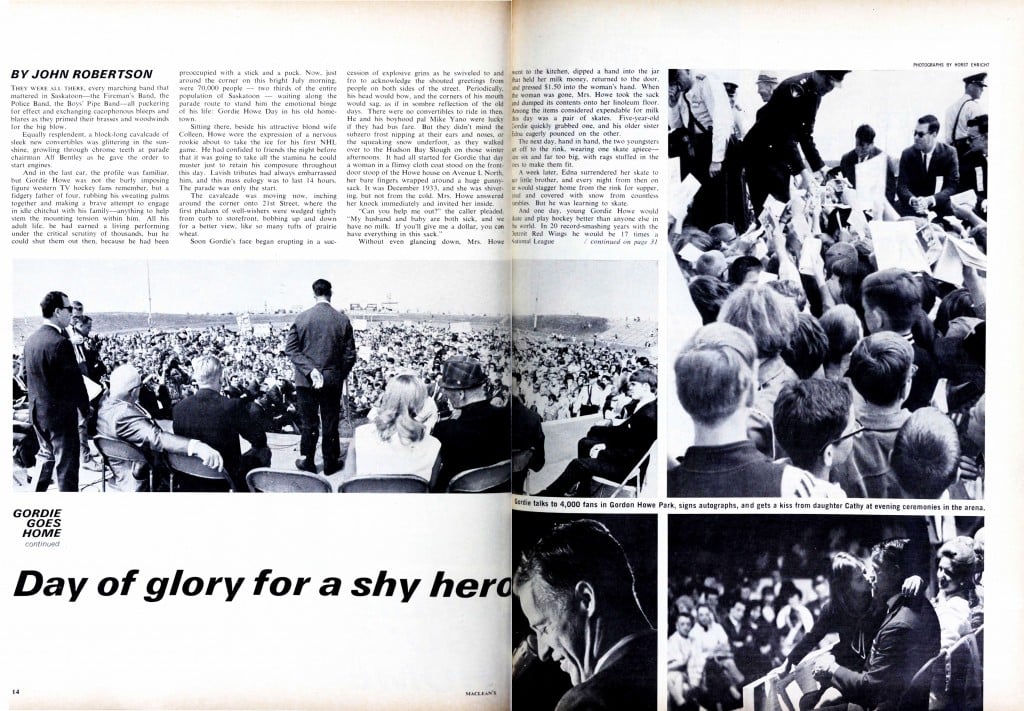

Gordie was scrambling just to keep his limbs intact later in the afternoon, when 4,000 youngsters converged on him as he stepped from the bus to mount a podium and officially dedicated Gordon Howe Park. It was really much more than just a playing area, because it contained a golf course, football field, baseball and fastball diamonds, a campsite and a hockey rink.

“Tough kid to tangle with”

“It’s nice to be among fellow teenagers,” he said once he got to the microphone. “Things weren’t that great here a few years ago. I used to sneak onto the golf course, and hide in a chicken house when the golf pro chased me.” The youngsters squealed with delight as their god exposed his clay feet.

“He used to come home crying when the other boys pushed him around,” Mrs. Howe recalled privately. “But he soon stopped that when I pushed him back out and told him to learn to take care of himself.”

Boyhood chum Mike Yano remembered him as “a tough kid to tangle with.” They first met while playing in Westmount schoolyard, when Gordie hit Mike on the knee with a frozen apple. Nobody owned a puck in those days. They used tin cans, rocks, or anything else round and hard. And Eaton’s catalogues made fine shin pads. Saturday was always a big day because then they could borrow their fathers’ work mitts.

“We never had much,” said Yano. who could remember when they used to wear running shoes to school almost year-around and would cut up cardboard squares to patch the holes in the soles. “Our idea of a treat was a slice of bread with some lard on it. And porridge? Sometimes we had it three times a day.”

Gordie stayed on to sign autographs for a full hour at his newly christened park, before he left to attend first a private family supper, then the big testimonial evening at the Saskatoon Arena. As he was boarding the bus, weariness was mirrored on his face. He turned to his wife and said. “This is harder on me than a playoff game.” But it was good to be home, back in the city he had left as a scared 16-year-old youngster, in 1944.

“When he went to Galt that year, I used to have a good cry every day,” said Mrs. Howe. “But we didn’t stand in his way, because hockey seemed to be his whole life.”

He was never much for school. His mother recalled how she had to talk him out of quitting half way through grade eight. “I told him that he’d never get anywhere without that grade-eight diploma.”

Hard bargain

That very first year, General Manager Jack Adams of the Detroit Red Wings knew he had a potentially great National Leaguer on his hands. But Gordie gave him a scare the day he came into Adams’ office to talk contract. Adams handed him a pen to sign on the dotted line, but Gordie balked. As Adams mentally calculated how much higher he’d have to go. Gordie announced his terms: “I want one of those Red Wing windbreakers — the kind the other fellows wear.”

Now it was evening, and 4,000 people who had each paid a dollar to $1.50 admission, were settling into hardbacked chairs at the Saskatoon Arena, looking forward to three hours of verbal tributes to Gordie from 14 hockey dignitaries, including NHL President Clarence Campbell.

The very idea of an almost-capacity crowd turning out to see Gordie Howe appear in a hockey arena in street clothes was a testimonial both to his personal popularity, and to the energetic promotional work of the Howe Day committee. The tribute was first proposed a year ago by staff members Stan Thomas, Les Edwards, Dennis Fisher and Cy Rouse of television station CFQC, which had gambled $12,000 in expenditures on the success of the day, after persuading civic politicians to rename the city’s new sports complex Gordon Howe Park.

Now, as he stepped onto the stage, Howe was looking refreshed by the quiet hours he had spent with his family at the dinner break. He was wearing his maroon Red Wing blazer and a pair of grey slacks. As he took his place beside wife Colleen and their four children Marty, 12, Mark, 11, Cathy, seven, and Murray, five – the people began springing from their chairs to give him a standing ovation. Two locally well-known broadcasters, Lloyd Saunders and Verne Prior, took turns introducing the speakers. Gordie stirred restlessly in his chair, bowing his head periodically and gripping the bridge of his nose with his forefingers as each superlative was punctuated by applause from the audience.

Doug Barkley, a former teammate whose hockey career ended abruptly last season when he suffered a serious eye injury, was telling the crowd, “I can’t wait for the day I’ll be able to say to my children that I once played with Gordie Howe and had him for a friend.”

Pierre Pilote of the Chicago Black Hawks pointed out how Gordie brought out the best in everyone he ever played against; and John Ferguson of the Montreal Canadiens got everybody chuckling when he said. “I know I have to go back to Richardland after I say this, but Gordie Howe is the greatest of them all.”

Other tributes soon followed, and then it was Jack Adams’ turn, and the former general manager of the Wings pulled a rumpled piece of paper out of his pocket and read a poem.

Isn’t it strange, that princes and kings,

And clowns that caper in sawdust rings,

And common folk like you and me,

Are builders of eternity?

To each is given a hag of tools,

A shapeless mass and a set of rules.

And each must make, ere life goes on,

A stumbling block or a stepping stone.

“Gordie Howe was given a hag of tools and I don’t have to tell you what he’s done with them,” Adams went on. “I know he’s made my life in hockey. And a big part of his success is the way he has treated his parents. We had some anxious times with him — that skull fracture many years ago against Toronto. As they wheeled him into the operating room, do you know what he said to me? ‘I’m sorry I didn’t help you more out there tonight.’ ”

Finally, as the arena clock was inching toward 11 p.m., it was time to hear from The Big Fella. He strode slowly to the rostrum, amid deafening cheers. His two smallest children, Murray and Cathy, tagged along on either side of him, tugging at his hands and digging into his jacket pockets, oblivious to the crowd. Tears welled in Gordie’s eyes as he began, ‘I feel like a small lost boy . . . I don’t know where to start thanking people … If I can live up to 10 percent of the things said about me here tonight, I’ll be a lucky man . . . I am a lucky man to have such fine friends and such a wonderful family. My ma? . . . well, she’s just the apple of my eye …”

Then he was bowing his head and trying to compose himself as he hugged his two youngsters with those massive forearms.

“It’s been an unbelievable day … all you wonderful people … and those thousands at the parade. Listening to all these words has kind of gotten to me. I hope you don’t mind if I shed a tear or two.”

Now just about everyone’s eyes were brimming, especially Mrs. Howe’s, who had first carried Gordie into Saskatoon in a baby shawl. The family had moved to town from the nearby hamlet of Floral when he was just nine days old. She might also have been wondering what would have happened 33 years ago if Gordie’s sister hadn’t given up that other skate.

Gordie had stopped returning to Saskatoon for the summer 10 years ago, and there had been some undercurrent of resentment in the city when he chose to live year around in Lathrup Village, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit. But that was all forgotten now; he had shown the people of Saskatoon a side of Gordie Howe all children could freely imitate with full parental blessing — Howe the attentive, loving son; the doting, exemplary father; the living legend who still has a lot of little boy in him.

“I’ve learned one thing,” said Gordie into the microphone. “I can never let all these kids down . . . put them in a position where they can do something wrong and then tell their parents that it can’t be bad because Gordie Howe does it, too.”

With that, 4,000 of his fans found out what they’d come here that night to learn: their Gordie hadn’t really changed a bit. He wasn’t perfect, mind you, but he came close.