Inside the Shafia killings that shocked a nation

From the archives: Michael Friscolanti’s longread tells the whole story of the Shafia “honour killings”

Mohammad Shafia, right, Tooba Yahya, centre, and their son Hamed Shafia, left, are escorted during a lunch break at the Frontenac County courthouse in Kingston, Ontario on Friday, January 27, 2012. (Nathan Denette/CP)

Share

At the conclusion of the Shafia “honour killing” trial in January 2012, Maclean’s senior writer Michael Friscolanti pieced together an exhaustive account of a crime that horrified so many Canadians. Years later, as the family continues to generate headlines, Friscolanti’s article remains a definitive narrative of the high-profile murder case.

Chapter 1

The police diver who swam to the bottom of the canal found Zainab Shafia in the front passenger seat, her face slumped forward, her fingernails painted a light shade of blue. She was 19 years old and had 10 cents in her pocket. Her black cardigan, drenched after hours underwater, was on backwards.

Sahar, her younger sister, was in the rear of the sunken Nissan Sentra, dressed in a pair of tight jeans and a sleeveless top. Her belly button was pierced (a stud with twin stones) and her nails were polished two different colours: purple on the fingers, black on the toes. As always, the stylish 17-year-old was within reach of her cellphone—about to become a crucial clue for investigators above.

Geeti’s lifeless body was floating over the driver’s seat, one arm wrapped around the headrest, the window beside her wide open. Like Sahar—the big sister she idolized—Geeti had a navel ring underneath her brown shirt. Detectives would later find a note she had scribbled to Sahar, full of hearts and red ink: “i WiSH 2 GOD DAT TiLL iM ALIVE I’LL NEVER SEE U SAD!” She was 13.

Rona Amir Mohammad was slouched in the middle back seat, her soaked black hair rubbing against Sahar’s. At 52, she was the eldest of the dead: the girls’ supposed “auntie,” but in fact their dad’s first wife in a secretly polygamous Afghan clan. The day she drowned, Rona put on a blue shirt, three pairs of earrings, and six gold bangles. She was not wearing a seatbelt. None of them were.

It was June 30, 2009, the morning before Canada Day. Det.-Const. Geoff Dempster was supposed to work the afternoon shift, two ‘til midnight, but his cellphone rang a few hours early. A colleague in the major crimes unit briefed him about the car full of corpses at the Kingston Mills locks, and asked him to come in as soon as possible. A few minutes after he arrived at police headquarters, three people showed up at the front counter to file a missing persons report: Mohammad Shafia, the girls’ father, Tooba Mohammad Yahya, their mother, and Hamed Shafia, their 18-year-old brother.

Dempster, a veteran cop with short blond hair and a rookie’s face, spent most of that Tuesday shift interviewing mom, dad and son, assuming, at first, that they were grieving relatives devastated to learn that their loved ones were gone. Their initial stories, videotaped for accuracy, were essentially the same. Wealthy Muslim family. Recent immigrants to Canada. Road trip to Niagara Falls, the 10 vacationers split between the Sentra and a silver Lexus SUV. Shafia, Tooba and Hamed all told the detective that they had stopped at a Kingston, Ont., motel on the way home to Montreal, and that Zainab grabbed the car keys to retrieve some clothes. The next morning, the Nissan—and nearly half the family—were gone. “That’s it,” Shafia said. “I don’t know anything else.”

But that was hardly it, as the detective soon realized. The more questions Dempster asked, the stranger their story sounded. Why would these women, after a six-hour road trip from Niagara Falls, pile into the Nissan for a middle-of-the-night joyride? Why did an eyewitness tell on-scene investigators that he saw two cars at the water’s edge that night? And why did the Shafias show up at the station in a green minivan—not the silver Lexus they were driving during the vacation?

Hamed, not a tear in sight, told the detective that he didn’t actually sleep at the motel with the rest of his family. Instead, he climbed back behind the wheel of the Lexus at two o’clock in the morning and continued toward Montreal, more than 300 km away. “I forgot my laptop,” he explained. He was home for only a few minutes, he said, when his dad phoned to tell him the girls were missing.

“How come you came back in the Pontiac?” Dempster asked, referring to the minivan.

“No special reason,” Hamed answered, mumbling about how the Lexus “takes more gas and fuel and stuff like that.”

“The reason for coming back in the Pontiac and not the Lexus was because it’s better on gas?” Dempster pressed.

“Well, that’s one of the reasons.”

“What would be another reason?”

“Nothing, uh, big,” Hamed replied. “Nothing, ya know, that’s worth telling.”

What police discovered over the next three weeks would tell a story so chilling, so unthinkable to most Canadians, that the resulting trial captivated the country like few crimes ever have. Mother, father, and eldest son—motivated by an ancient, barbaric “honour” code—used their Lexus to smash that Nissan over the lip of the Rideau Canal, watching with perverted satisfaction as all four females vanished into the water. “I am happy and my conscience is clear,”Shafia proclaimed the night before his arrest, unaware that a police wiretap was recording his every word. “They haven’t done good and God punished them.”

Today, a different punishment looms: life behind bars. After four months, 58 witnesses, and too many lies to count, a jury found Shafia, Tooba and their beloved Hamed guilty of quadruple murder in the first degree. It took just 15 hours of deliberation for the jurors to reach their verdict.

The evidence, utterly heartbreaking, left no real doubt about the truth. Before they died, the Shafia sisters were caught in the ultimate culture clash, living in Canada but not allowed to be Canadian. They were expected to behave like good Muslim daughters, to wear the hijab and marry a fellow Afghan. And when they rebelled against their father’s “traditions” and “customs”—covertly at first, then for all the community to see—the shame became too much to bear. Only a mass execution (staged to look like a foolish wrong turn) could wash away the stain of their secret boyfriends and revealing clothes.

Rona, it turns out, was simply a convenient throw-in, the infertile first wife who died as she lived. An afterthought.

“They committed treason from beginning to end,” Shafia declared, during another one of his intercepted rants. “They betrayed kindness, they betrayed Islam, they betrayed our religion and creed, they betrayed our tradition, they betrayed everything.”

His daughters died because they were defiant and beautiful and had dreams of their own. Because they were considered property, not people. But the two words at the heart of this sensational case—“honour killing”—do not tell the whole twisted tale. What happened on that pitch-black night is also a story about cries for help that were missed or ignored. About sibling rivalry and family snitches. About young love and old-fashioned police work.

And it’s a story about a custom-built courtroom, where father, mother—but not son—took the stand to proclaim their innocence.

Chapter 2: The roots of a tortured clan

By Western standards, Mohammad Shafia is not an educated man; born in middle-class Kabul in the early 1950s, he didn’t reach the seventh grade. But as an entrepreneur, he was gifted and ambitious, a stingy deal-maker who turned a small electronics shop into a multi-million-dollar import-export operation. His specialties were Panasonic radios and Peacock brand thermoses, shipped in from Japan. “It was only me,” Shafia told the jury, the pride still evident in his raspy voice. “I had the monopoly on importing those.”

Like many in Afghanistan, Shafia‘s first marriage was an arranged one. It was his mother who first spotted young Rona Amir, the pretty daughter of a retired army colonel. Three decades later, police on the other side of the world would find Rona’s diary, detailing the events that led to her wedding day-and the years of “torture” that followed.

”[Shafia‘s mother] invited all of us to her house so that her son could have a good look at me,” she wrote in her native Dari. “After our visit her son announced his consent.” When one of Rona’s brothers asked if she “accepted” the union, her answer was eerily prescient: “Give me away in marriage if he is a good man; don’t if he is not.”

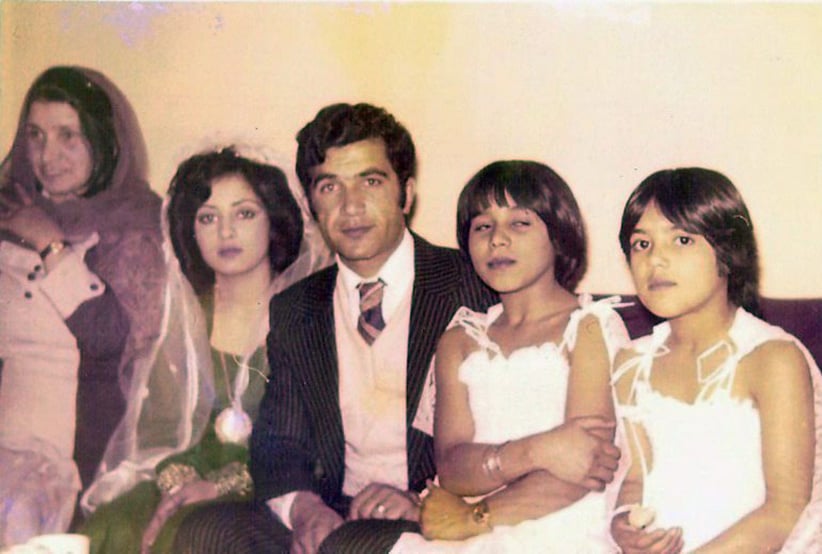

They were married in February 1979, with a swank reception at Kabul’s Intercontinental Hotel. The bride wore a frilly dress, baby blue, with a matching veil. The groom sported a purple suit and long sideburns. In one wedding snapshot, Rona and Shafia are smiling beside their cake, three layers covered in pink and yellow icing. “After getting married,” Rona would later write, “my lot in life began a downward spiral.”

Sadly, Rona was unable to conceive. For years, she and Shafia tried to have children, even travelling to India for repeated fertility treatments. Nothing worked. “My husband started picking on me,” she wrote. “He wouldn’t allow me to go visit my mother, and at home he would find fault with my cooking and serving meals, and he would find excuses to harass me.” Finally, after nearly a decade without a baby, she told Shafia: “Go and take another wife, what can I do?” He did.

Tooba Mohammad Yahya was 17 years old, a relative of one of Shafia‘s friends. He was double her age, old enough to be her father.

Shafia said it was Rona who handpicked his second bride, and Rona who happily planned the reception (at the same posh hotel, with her in the wedding party). “She told me: ‘Children are important to us and I want you to find another woman to marry,’ ” he said. “That was her agreement.”

Rona’s recollection was somewhat different. “I was visited with a new catastrophe.” (Tooba wasn’t exactly thrilled, either. On the day of her arrest, while sitting in the back of a police car, an officer asked if she loved her husband. “I was not in love,” she answered, in between sobs. “But I fell in love after we got married.”)

In a photo from wedding number two, Shafia is dressed in a black suit and matching moustache, his new bride on one arm, his first on the other. The wives called him “Shafie.”

They were not a family of three for very long. Within weeks of the wedding, Tooba was pregnant with Zainab, the baby her new husband so badly wanted. The moment wasn’t captured on camera, and Shafia never mentioned it during hours of police interviews and courtroom testimony. But in September 1989, he held his tiny daughter for the first time, cradling her in the same hands that, years later, would take her life.

At home, Rona played the obligatory role of surrogate mother, helping Tooba care for the baby and tend to chores while still praying for a child of her own. Yet even then, in the early months of their polygamy, Rona realized what was happening. Tooba, fertile and conniving, had “schemed to gradually separate” her from their shared spouse. “After their son Hamed was born,” Rona wrote, “happiness left me.”

In a diary dripping with heartache, Sahar’s arrival, in October 1991, was a rare moment of joy. Tooba “gave” the baby girl to her barren fellow wife to raise as her own.

But it wasn’t long before Tooba made another announcement: “Shafie should stay three nights with her and one night with me,” Rona recalled. “Because she had given Sahar to me, I agreed.” Soon, Shafia stopped sleeping with his first wife altogether.

Sahar was still a baby when Afghanistan’s civil war crossed into the capital city, killing hundreds and displacing thousands. The Shafias, fleeing by car, arrived at the Pakistani border as a family of six: Rona, Zainab and Sahar, destined to die at the Kingston Mills locks. And Shafia, Tooba and Hamed, destined to stand trial for their murders.

At the time, Tooba was pregnant with her fourth child, another daughter. The girl’s identity is protected by a publication ban (we’ll call her “A”). But during the trial, jurors heard plenty of evidence about her eventual role in the Shafia household: a standout student who spied on her sisters and reported back to mom and dad. “B,” a second son, was also born in Pakistan. He, too, would be cast as a family snitch, tattling on the girls and defending his parents from the witness stand.

Geeti-the youngest daughter fished from the canal-was baby number six. After she was born, the family started packing yet again, this time for the United Arab Emirates. Shafia launched a new company (M. Shafee Trading) and business was better than ever; barely a year after arriving in Dubai, Panasonic awarded him $50,000 for being the top seller in the region. He would later expand his operation to include used cars imported from the United States-purchased, ironically enough, from online auctions that specialize in damaged vehicles.

It was in Dubai that Shafia‘s kids tasted Western culture for the first time. Although the UAE is an Islamic country, the children attended a private American school, where they wore uniforms, learned to speak English, and met kids from around the world.

For Rona, though, the move left her more marginalized than ever. She wrote about Tooba learning to drive, buying as much gold jewellery as she pleased, and implementing “all the schemes she had” to position herself as the preferred wife. “Not aggressively, through shouting and quarrelling, but gently and smoothly, without putting herself at risk of any censure,” Rona recalled. “Miserable me who wouldn’t question Shafie in regard to anything swallowed everything without a word, because I had no option.” (While in Dubai, Tooba gave birth for the final time. “C,” now in foster care, is subject to the same publication ban as her siblings.)

Although the Shafias stayed in Dubai for more than a decade, they spent much of that time searching for a new home, a place that could offer them citizenship, not just residency. At one point, the family tried to immigrate to New Zealand, but Rona didn’t pass the required medical. They even spent a brief period in Australia, only to return to Dubai within a year. (Tooba said she and the children didn’t like Australia, but Rona claimed they were deported because her husband-“the silly fool”-ignored the rules of his visa and purchased property.) Whatever the reason, Rona felt the brunt of her husband’s wrath. “Whatever I did, if I sat down, if I got up, if I ate anything, there was blame and censure attached to it,” she wrote. “In short, he had made life a torture for me.”

By 2007, Shafia had finally found his ticket out of Dubai: Quebec’s immigrant investor program, which provides visas to affluent foreigners in exchange for, among other things, a hefty cheque made out to the province. (Back then, the required amount was $400,000; it has since doubled to $800,000.) Shafia had no trouble covering the cost. His only challenge was figuring out how to hide the truth about his two wives, a violation of Canadian law that would have certainly derailed his application. In the end, he listed only one spouse on his paperwork: Tooba. ?

So in June 2007, while the rest of the family boarded a plane to Canada, Rona was sent to live with relatives in Europe while Shafia concocted a plan to bring her here. It was the first time she had ever been separated from the others, and to her own surprise, she missed them terribly. “It was really unbearable,” Rona wrote. “No one can read the future. I wish I hadn’t [missed them] so much.”

One of the first things Shafia did when he landed in Montreal was purchase a new car: a silver Lexus SUV.

Chapter 3: A home becomes a snakepit

On paper, at least, Mohammad Shafia was the ideal immigrant investor, anxious to funnel his fortune into Quebec’s economy. Within months of his arrival, he bought a $2-million strip mall in Laval (most of it in cash) and launched an import-export firm that dealt in clothing, household goods and construction material. He settled on the upscale suburb of Brossard to build his $900,000 mansion, with plenty of space for all 10 members of the clan: himself, two wives, and seven kids.

While waiting for the home to be finished, the Shafias spent two years squished into a rental home in the borough of Saint-Leonard, split between four bedrooms and two bathrooms. They didn’t even bother to unpack most of the furniture from Dubai; instead of beds, the children slept on brown mats spread out on the floor. It looked hardly the home of a globe-trotting businessman.

What happened between those walls, from June 2007 to June 2009, was the subject of so much conflicting testimony that not even the dead know the full truth. But according to the prosecution’s narrative, gleaned through dozens of witnesses, that brick fourplex on Rue Bonnivet was a virtual prison, a remnant of 14th-century Afghanistan smack in the middle of cosmopolitan Montreal. Although Shafia had moved his daughters to the freest of countries (and given them endless money to eat fast food and buy expensive clothes) he expected them to uphold his twisted sense of honour. Just talking to a strange boy was enough to destroy the family’s reputation.

By the fall of 2007, six months after everyone else arrived, Rona was finally on her way to Canada. She arrived on a temporary visitor visa, her husband’s supposed “cousin” and live-in nanny. Friends and relatives knew that Rona was Shafia‘s first wife, but until she died, the government had no idea.

She was greeted by the same old Tooba. “Your life is in my hands,” she would say, according to Rona’s diary. “You are my servant.” Rona moved into a bedroom with Geeti and Sahar, their sleeping mats side by side.

The brothers, Hamed and “B,” shared another bedroom, as did Zainab and her younger sister “A.” The youngest, “C,” slept with mom and dad in the master suite. Most nights, though, it was just Tooba and the child, as Shafia spent much more time in Dubai than he ever did in Montreal. During those two years before his arrest, he was in Canada for a total of only six months.

And during those many overseas business trips, Hamed was left to enforce the house rules-his father’s eyes, ears, and fists.

Zainab, though older, knew full well not to cross her kid brother. They were attending the same Montreal school in February 2008 when a Pakistani classmate sent her a Valentine. She responded with a covert email. “Be aware of my bro,” Zainab wrote. “If my bro is around act like complete stranger . . . we’ll talk if my bro is not around coz i don’t want to give him the slightest idea that we r friends.”

Ammar Wahid stuck to the ploy, but it didn’t last long. Barely a month after that email, while both her parents were visiting Dubai, Zainab invited her new boyfriend to the house, unaware that Hamed was on his way there, too. He found Wahid hiding in the garage, shook his hand, and asked him to leave. Zainab-18 years old-never returned to that school, and for the next 10 months she was essentially banished to her room. She didn’t go to school, and couldn’t leave the house without a relative at her side.

Sahar was trapped in her own silent hell. She was 16, still adjusting to life in Canada, when her mother accused her of kissing a boy. Tooba even stormed into the school and cornered one of Sahar’s teachers. (Her little sister, “A,” acted as their mom’s translator.) “She was very angry,” said the teacher, Claudia Deslauriers. “She said she did not accept her daughter kissing a boy, and that it did not fall within the parameters of her values.”

Depressed and suicidal, Sahar peeled open one of those white silica gel packets from a shoebox and mixed it with water. Rona and Geeti were hysterical, rushing to Sahar’s side after she drank it. But as Rona recalled in her diary, Tooba didn’t budge from the kitchen: “She can go to hell. Let her kill herself.”

Sahar didn’t die that night, but what she did next helped seal her fate.

Batshaw, Quebec’s anglophone child welfare agency, received the call on May 7, 2008. Red with tears, Sahar was sitting in her vice-principal’s office, spilling everything. Hamed flinging a pair of scissors at her hand. The suicide attempt. Pressure to wear the hijab. “A” the spy. Sahar said her mother had barely talked to her in months, and had ordered the other kids to ignore her, too.

Evelyn Benayoun, a Batshaw intake worker, was on the other end of the phone. “When I initially asked what she wanted, she said: ‘I want my mother to speak to me,’ ” Benayoun said. “She said she was wishing to die that day, but didn’t know how to kill herself.”

The veteran social worker classified the call as a “Code 1,” immediately dispatching a colleague. But when Jeanne Rowe arrived at Antoine-de-St.-Exupery high school, she encountered a very different Sahar. Though still sobbing, she denied everything. “Before I could even meet with her properly, she kept saying: ‘I don’t want you to meet with my parents. I want to go home,’ ” Rowe said. “She was very, very scared of her parents knowing about the report. She didn’t explain why.”

Following protocol, Rowe did phone the house. Tooba arrived at school first, Zainab in tow. She refuted everything, including the suicide story. (Zainab-under house arrest for her own defiance-agreed with her mom, but she did tell the worker that Sahar was “sad” about having to wear the hijab.) Shafia walked in a few minutes later, Hamed at his side. “He was quite angry, and he wanted to know the source of the report,” Rowe said. “I told him I could not give him the source, and he said he would speak to his lawyer because the report was nothing but lies.”

Two days later, when Rowe returned to the school for a follow-up visit, Sahar was wearing a hijab. “There were no tears, but she was still very cautious and minimized the situation,” Rowe recalled. “You have to make an assessment if the child is at risk. The child was not at risk at the time, she wanted to go home, so we closed the case.”

At home, though, nothing changed. Rona spent her days wandering through parks and using pay phones to confide in relatives overseas. “She would go outside and cry,” said Diba Masoomi, her sister. “She was saying: ‘I am fed up with my life and I want God to finish my life. I want to be in an accident.’ “

One relative was so concerned about Rona that she put her in touch with another distant family member: an Afghan women’s rights advocate living in Virginia. They never met face to face, but in the year leading up to her death, Rona would phone Fahima Vorgetts up to three times a week. Not once did she call from the house. “She said her husband would humiliate her and beat her up,” Vorgetts recalled. “I encouraged her to take classes, to learn something. She said she’s not allowed to do that.”

Rona wanted a divorce, but didn’t want to leave the children. Her husband ignored and abused her, but wouldn’t let her go. (“He told her he will kill her if she leaves,” Vorgetts said.) And hovering over everything was her unsettled immigration status. Although her visitor visa had been extended numerous times-and a lawyer was working on her application for permanent residency, at Shafia‘s expense-Rona’s life in Canada was predicated on a lie, and could end at any time.

Shafia, it turns out, was also concerned about her immigration file-for a very different reason: if the government discovered the truth about their relationship, the entire family could face deportation. The jury never heard this piece of evidence, but Shafia allegedly offered the lawyer $10,000 to somehow send Rona back to Afghanistan.? A few months after her 19th birthday, Zainab was finally allowed to return to school (though not the same one where she met Wahid). She took morning classes by herself, and a French night course with Hamed and her mother. During a rare moment alone, she emailed her old boyfriend. “I miss you bad,” she told Wahid. “I still rem the way u told me u love me the first tym.” At the end of the note, Zainab said she still cried about the day her brother caught him at the house. “Babi work hard,” she wrote. “Make sumthing out of ur self i will be so happy.”

By the beginning of 2009, they were sneaking visits once again. Sometimes at McDonald’s. Sometimes at the library. And sometimes with Sahar-and her new boyfriend.

It was Zainab, defiant to the end, who first introduced the couple. Ricardo Sanchez, a recent immigrant from Honduras, was enrolled in her French class. He was 21 at the time, four years older than her younger sister, but Zainab wanted him to meet Sahar so badly that she brought him to her school. They could barely communicate (he spoke Spanish, she spoke English) and for the first little while, Ricardo thought her name was Natasha. But they were soon spending every possible moment with each other: lunch breaks, weekend afternoons, 4 o’clock visits to a restaurant near the school. “It was very serious,” Sanchez testified. “We could get married, I was telling her. And she was agreeing.”

Sanchez was living with an aunt, Erma Medina, when he first came to Canada. “Sahar told me her parents didn’t know about her relationship with Ricardo,” Medina said. “The day her parents knew, she would be a dead woman. She told me that several times.”

Geeti knew about Sanchez. She knew everything about Sahar. They were as close as two sisters could be.

But Geeti, now 13, was her own breed of rebel. She never lived a day in Afghanistan, and grew up among the privileged at a Dubai private school. Now in Canada, she had absolutely no interest in her father’s conservative traditions-and didn’t much care if he knew it. She loved makeup and fashionable clothes, and on the days she didn’t skip school, Geeti hid out in the bathroom.

During parent-teacher interviews, Shafia complained about his daughter pulling the same antics in grade school, and asked that her behaviour be logged in a daily agenda book. “There was an agreement reached,” said Fatiha Boualia, her math teacher. The very next school day, Geeti didn’t show up.

It was hardly a surprise, then, that Geeti was at the centre of one of her father’s most violent outbursts-a beating that became a focal point of the trial.

In early April 2009, she was at a mall with her sister and brother (“A” and “B”). When they arrived home late, Shafia was so enraged that he and Hamed lashed out at all three of them, screaming and slapping. “A” and “B” would later downplay the incident. Geeti, stubborn like a rock, did not.

For Zainab, who watched it all unfold, the abuse had become unbearable. Days later, she made a gutsy decision that rocked her family to the core. She escaped.

Hamed was frantic enough to phone 911, telling the dispatcher that his older sister-a few months shy of her 20th birthday-had run away. “She stay at home usually,” he said. “She left a note and, uh, she’s nowhere to be found.” Asked what the note said, Hamed replied: “I would like, uh, to live my own life.”

A few minutes after hanging up, Hamed called 911 again. “They didn’t come yet,” he told the dispatcher.

Chapter 4: A vicious plan takes shape

Zainab “ran away” on Friday, April 17, 2009, taking refuge at a women’s shelter. For Shafia, it was a monstrous betrayal. His adult daughter was out in the world, unsupervised, unrestrained. She could be having sex. And even if she wasn’t, people would think that, which is just as bad.

Her courage, her thirst for freedom, is what got her killed just 10 weeks later. But what began as a conspiracy to punish her, and only her, quickly spiralled into mass murder. One bad apple became two bad apples. Two became three. And three became four.

The day Zainab left, news of her disappearance trickled back to her teenaged siblings at school. The four of them (Sahar, Geeti, “A,” and “B”) were so terrified of their father’s reaction that instead of going home, they went to a stranger’s house and asked him to phone the police. Add in Hamed’s attempts, and it was the third 911 call of the afternoon linked to the Shafias’ address.

Ann-Marie Choquette was one of the Montreal constables who responded to the scene. She and her partner found the kids standing on a street corner, still too afraid to go home, and escorted them the rest of the way. Outside the house, Choquette interviewed each of them, alone.

Geeti told the officers about the mall incident the week before, how dad pulled her hair and Hamed punched her in the face. She also said, without hesitation, that Shafia “often threatened that he was going to kill them.”

Choquette noticed that “A” had “a mark near her right eye” and asked about the injury.What “A” said has never been disclosed.

“B,” her brother, told the officers that Hamed kicked him and that his dad threatened to “tear him apart.”

Like Geeti, Sahar said Hamed had slapped her, and that she watched as Shafia beat Zainab because of her boyfriend. She and Geeti also said “they wanted to leave the home because there was a lot of violence” and “they were afraid of their father.”

The kids were still outside when Shafia pulled into the driveway. According to Choquette, he “just looked at the children” and they stopped talking. In tears, “A” immediately recanted whatever it was she said, insisting it wasn’t true.

A worker from DPJ, Quebec’s francophone child welfare agency, was also dispatched to the house that night. (It was Batshaw, the anglophone service, that responded to Sahar’s original complaint the year before.) The social worker spoke to Shafia, Tooba, and Hamed, but decided it was safe to leave the kids and continue his investigation after the weekend. Choquette thought there was ample evidence to lay a criminal charge, but following standard protocol, she left that decision to DPJ.

Choquette did see Shafia and Hamed again-that Sunday, at the police station. They were anxious to know if she had any updates on Zainab’s whereabouts. She didn’t.

On April 20, the Monday after Zainab left, the case file landed on the desk of Laurie-Ann Lefebvre, a Montreal detective who worked the child abuse beat. Accompanied by the DPJ worker, she visited the kids’ school and re-interviewed three of the four (“B,” the brother, was absent that day). Although “A” continued to recant, the other two did not back down. Geeti wanted “immediate placement” in foster care because “she had no freedom,” while Sahar provided more details about her abusive older brother. When their dad was away, she said, Hamed was “the boss.”

Sahar was wearing makeup and jewellery, and no hijab. “She explained that she would change her clothes at school in the morning, and again before going home,” Lefebvre said.

No charges were laid. For reasons that remain unclear, DPJ also closed its file.

The warning signs, though, were everywhere. While Zainab was gone, Geeti didn’t go to school for more than a week. Sahar did, but was often in tears, shielding the truth about her sister by telling teachers and classmates she was in a coma. At the end of April, their daughter still in hiding, Shafia and Tooba were summoned to the school yet again, this time to discuss the kids’ slipping grades and poor attendance.

“The father was really in a state,” said Nathalie Laramée, the assistant principal who convened the meeting. “He was speaking very loudly in my office. ‘What can we do? What can we do?’ ”Shafia kept repeating the word “policia.” After mom and dad left the meeting, “B” told Laramée that the cops did visit the house, but that things at home were improving. When their brother left, though, Sahar and Geeti told a much different story. “Sahar said: ‘My sister and myself are afraid in the house, and we know that when we are in school we have to be careful because our behaviour is reported back.’ “

They had eight weeks to live.

Zainab was still in the shelter when Rona overheard a conversation so terrifying that she shared it with her sister in France. “I will go to Afghanistan,” Shafia told Hamed and Tooba. “I will prepare the documents, I will sell my property, and I will kill Zainab.”

“What about the other one?”

“I will kill the other one, too,” he said.

Rona was sure that “the other one” was her. “She was shivering,” her sister said. “She was afraid. I told her: ‘Don’t be afraid. This is not Afghanistan. This is not Dubai. This is Canada. Nothing will happen.’ “

Eventually, Zainab did make contact with her mother. In fact, it was Tooba who convinced her daughter to come back home, promising that if she really did love Wahid, they could get married. Zainab walked through the front door on May 1, 2009, right after her dad flew to Dubai for another business trip.

As the wedding day approached, Tooba kept pressuring her daughter to back out. She even enlisted the help of one her brothers, Fazil Javid, who ran a pizza parlour in Sweden. But after numerous telephone conversations, Javid said he realized exactly what Zainab was doing. “She wanted freedom,” he explained. “She said: ‘I know it’s not my time to get married, but I’m forced to marry to get out of this house.’ “

At the very least, Javid wanted to travel to Montreal to meet Wahid and his family, to make sure the Pakistani could provide a proper life for his niece. Out of respect, he phoned his brother-in-law in Dubai to make sure he accepted such a visit. “But Shafia had a request for me,” Javid said. “He told me this plan he has to fulfill: the murder of Zainab.”

According to Javid, Shafia called his daughter a “whore” and a “prostitute,” and outlined a plot to end her life and maintain his honour: Javid would invite some of the family to Sweden, plan a picnic near some water, and they would throw Zainab in.

Javid said he swore at Shafia and hung up the phone, then scrambled to warn both Tooba and another brother living in Montreal. His sister thanked him (“It’s very good that you told me,” she said) but for reasons that he never fully explained, Javid didn’t directly warn his niece.

With Shafia out of the country, Sahar was spending even more time with Sanchez, her cellphone photos a chronicle of their young, forbidden love. Cuddling on a living room chair, her arm wrapped around his. Smiling in a pair of sunglasses, his hand resting on her stomach. In one shot, Sanchez is not wearing a shirt. In another, the couple is standing on a porch, Sahar wearing a short jean skirt and a yellow top. They were talking about running away to Honduras. “She loved Ricardo,” his aunt recalled. “She told me that she would love him till death.”

Part of Sahar’s dream was to rescue Geeti. At school one day, she asked Boualia, their math teacher, if she would be allowed to take her little sister if she ever moved out. Boualia advised against it, telling Sahar that a 13-year-old girl belongs with her parents. When Geeti found out, she was inconsolable, to the point that Boualia and a vice-principal spent an entire lunch hour trying to calm her down.

Geeti didn’t show up to school for days. When she died seven weeks later, police found a page in one of her notebooks, full of affectionate doodles to her big sister.

S+G 4LYFE

i DON’T KNOW if ONE DAY YOU LEAVE THiS HOUSE WAT AM i GONNA DO????

i PROMiSE BEFORE DYING i’LL MAKE UR WISHES CUM TRUE ONE BY ONE

Back at home, Zainab could not be dissuaded. She was going to marry Wahid, regardless of what her family thought. So with Shafia still in Dubai-murder already on his mind-Tooba phoned an uncle, Latif Hyderi, and asked him to organize the nikah, the Islamic marriage ritual. The Shafias, hardly religious to begin with, had not stepped foot in a mosque since arriving in Canada. Hyderi made all the arrangements, finding a mullah and booking a restaurant for the reception.

The ceremony took place on May 18, six weeks before the bodies were found. “Everyone, their heart was bleeding,” Hyderi said. “Marrying a foreigner affected everybody.”

The next morning, before the reception, Zainab had her hair styled and her hands painted with henna. Hyderi drove her to the restaurant, and on the way he tried to counsel Zainab, one last time, to reconsider the marriage. But her answer was clear. “Dear uncle, there has been a lot of cruelty toward me,” she said. “I sacrifice myself for my sisters so they will get this freedom after me.”

That freedom, it turned out, was short-lived. Nobody from the groom’s family showed up (ironically enough, they didn’t approve of the union, either) and her mother was in tears, the embarrassment too much to stomach. “Tooba just fainted,” Hyderi recalled. “She fell on a chair. People were throwing water on her. Zainab threw herself on the chest of her mother and said: ‘If you do not agree, I will reject this boy.’ “

Like so much about the Shafias, the events of that day depend on who is doing the remembering. But one thing is certain: Zainab asked for a divorce, and Wahid agreed. “She said: ‘I can’t do this, I can’t ruin my family’s reputation,’ ” Wahid said. “Obviously, we loved each other, so it hurt both of us.”

The mullah declared them divorced right at the restaurant. They were husband and wife for barely 24 hours.

Back at Hyderi’s house, Tooba was still bawling. But by the end of that night, a plan was already hatched to restore the family honour (or, as Hyderi put it, to “remove the stain from Zainab’s skirt”). She would marry one of his sons, a good Afghan boy.

When Hyderi phoned Dubai, Shafia seemed to approve of the idea. He made it clear, though, that he didn’t want the boy anywhere near his daughter until he returned to Canada. “He said: ‘I’m not happy. She didn’t do a good thing,’ ” Hyderi recalled. “He said: ‘If I was there I would have killed her.’ “

A few days later, inside a different restaurant, Sahar was hugging Sanchez. By the time she noticed her younger brother walk in, it was too late. “He started to ask if Sahar was my girlfriend,” Sanchez said. “I told him we had just met.” Desperate to conceal the truth, Sanchez even kissed one of Sahar’s friends.

Sahar was petrified that “B” would reveal her secret. On May 30, exactly one month before she died, she fainted in class and had to be rushed to a hospital.

But by then, it appears, her secret was already exposed. On June 1, Hamed hopped on a plane to join his father in Dubai, and when investigators later searched the house, they found that boarding pass stuffed inside his suitcase-along with numerous photos of Sahar and Sanchez, taken straight from her cellphone and developed into prints.

They were proof of her dishonour. Proof that she, too, deserved to die.

As soon as her brother left, Zainab sent another email to her now ex-husband. “We had an amazing love story 2gether,” she wrote. “It was my dream to marry u n i did it once soooo nw even one day if sum thing happens to us like dead I wnt die with out my dream being full filled.”

The very next day, June 3, someone in Dubai conducted a Google search on Hamed’s Toshiba laptop: “Can a prisoner have control over their real estate.”

That Monday, June 5, Sahar told a teacher how worried she was. As the teacher put it, “she was afraid that her brother was going to tell her father that she was a whore.” The 17-year-old was in such a state that the teacher phoned DPJ, yet again. The worker on the other end suggested that she find a shelter.

In Dubai, the Google searches continued: “canada mountains with lake in Quebec.”

At school that Monday, Sahar met with another social worker. Like so many times before, she told Stephanie Benjamin about her tyrant of an older brother and her desire to find a job. She also opened up about her ultimate dream: to become a gynecologist and help women in her native Afghanistan.

The next night, June 9, Zainab sent another email to Wahid. She had not seen her dad since fleeing the house, and he was due home in just a few days. “i mst go to da airport n say srry,” she wrote. “i hope he 4gets every thing.” She would be dead in three weeks.

Geeti was hardly going to school at all. She was failing all four classes, and the one day she did bother to show up, a vice- principal sent her home for wearing a low-cut sweater. While Shafia was gone, Geeti was also caught shoplifting at Wal-Mart; she tried to steal a pink camisole and some leggings.

Geeti was growing more brash, more uncontrollable, by the day. She told anyone who’d listen that she wanted out of the house. And as Hamed and her parents no doubt realized, she would not keep quiet if Zainab and Sahar turned up dead. She would be the first one to call the cops and blow the whistle.

She, too, had to die.

That June, Fahima Vorgetts, Rona’s relative in Virginia, returned home after a month spent working in Afghanistan with her U.S.-based group Women for Afghan Women. On her phone were numerous voice mails from Rona: “I really need to talk to you.” “They were desperate messages,” Vorgetts recalled. “It sounded like she was in big trouble. It seemed to me like she wanted to do something.” But because Rona always used a pay phone, Vorgetts had no way to reach her. “She never called back. And then I heard that she was dead.”

Shafia and Hamed landed in Montreal on June 13, 2009. By all accounts-including his own-Shafia kissed Zainab on the head and forgave her for everything. (In his version, he also slipped her $100.) But nothing, of course, was truly forgiven. He just wanted his daughter to feel comfortable, to assume that things were fine.

Back at the house, the Google searches intensified.

“mountains on water in quebec”

“to rent a boat in montreal”

“facts documentaries on murders”

On June 19, Hamed cancelled Zainab’s cellphone plan. The day after that, his mobile phone travelled all the way to-and all the way back-from rural Grand-Remous, Que., nearly 300 km from their Montreal neighbourhood. His Internet research had escalated into full-blown reconnaissance.

At home that night, Hamed’s laptop conducted yet another Google query: “where to commit a murder.” His sisters and his stepmother had 10 days to live.

On June 22-the morning after Father’s Day-Sanchez typed a text, in Spanish, to Sahar. “I love you with all my heart and I can’t love anybody more beautiful than you because you are like the air that I breathe every morning, the sun that warms me up,” he wrote. “I want only you to be the owner of my heart.” Thirty minutes later, he sent another: “The only thing that I would wish in this world is to have you every day of my life.”

A few hours after Sahar read that message, her father purchased a used car: a 2004 Nissan Sentra, black with grey interior. The next afternoon, the trunk was full of luggage, packed for a summer “vacation.”

Chapter 5: Driving into the darkness

As far as the children knew, they were going on a road trip to Vancouver. Or Niagara Falls. Or somewhere else. The destination was never clear. But that’s because the destination was not the point. Going on “vacation” was all part of the plan.

On the way out of town, while stopped at a fruit store, the family caravan bumped into Latif Hyderi. By then, Tooba’s uncle was anxiously waiting to hear from Shafia to finalize the engagement plans for Zainab and his son. “Tooba looked very scared, and she was in an unusual condition,” Hyderi recalled. “I told her: ‘This girl is our trust with you. You have to bring her back safe and sound.’ ” He watched them drive away.

When Fazil Javid heard about the vacation, he couldn’t stop thinking about that phone call with his brother-in-law. The trip to Sweden. The picnic by the water. The murder of Zainab. “I was seeing all those scenes like a movie,” he said. “I thought something was going to happen.”

So many details-the car-ride chatter, the rest-stop meals, the hushed whispers between conspiring killers-will never be fully known. But because Sahar spent so much of the journey rifling off text messages, investigators were able to retrace the family’s precise route, minute by minute, cell tower by cell tower.

Split between the Lexus and the Nissan, the Shafias left Montreal shortly after 3 p.m. on June 23. They headed straight to Grand-Remous, the same faraway place that Hamed visited the day his laptop was churning out hits for “where to commit a murder.” When they arrived, just before sunset, the sisters met a woman walking some puppies. Sahar snapped a photo of Geeti holding one of the dogs, the fur pressed up to her face. Shafia and Hamed took a walk.

If Grand-Remous was supposed to be the crime scene, something altered the original plan. Because after sleeping at a motel-and stopping for a waterside barbecue of chicken kebabs-the family got back inside the cars on June 24 and headed south toward Ottawa. Plotted on a map, their trip to that point was basically a 450-km horseshoe.

As investigators discovered, the route got even more suspicious.

Barrelling westbound along Highway 401, through Brockville and Gananoque, Sahar’s text messages pinged off each passing cell tower. But for at least 40 minutes-between 8:36 p.m. and 9:16 p.m.-her phone utilized just one: a tower within plain sight of Kingston Mills, a historic lock station at the southern tip of the Rideau Canal. As bathroom stops go, it wasn’t close to the highway. Sahar continued typing, unaware that another reconnaissance mission was under way.

Back in the car, the family kept driving all the way to Niagara Falls, reaching their motel in the wee hours of the morning, June 25.

If the cellphone photos were the only evidence, Sahar was a typical teenager on a typical family vacation. She snapped a shot of her and Zainab standing in front of the bathroom mirror. Her and Rona dressed for dinner. Herself in a green and brown bikini. But her actual phone records revealed something much more sinister, providing police with one of their most critical clues.

On the night of June 27, just two days after the Shafias arrived in Niagara Falls, someone using Sahar’s phone dialled Hamed’s number. The resulting signal bounced off a tower just 16 km from the Kingston Mills locks. Hamed or Shafia (or both) had left the rest of the family and driven five hours back, to stake out their chosen crime scene one last time.

Sahar (if it was her who dialled the number) had no way of knowing that Hamed’s cell was all the way in Kingston. Only after she died, when investigators scoured her phone logs, did that lead come to light. But what is clear is that Sahar seized on her brother’s absence, talking to her boyfriend for more than an hour that night. They snuck in two more calls the next morning.

That afternoon, June 28, Sanchez rifled off more text messages, each one professing his love. “The world is so large that one day I could lose you,” he wrote. “Every time I close my eyes I only think of you. And every time I close my eyes I only want to see you.” The last one arrived at 6:19 p.m. “If I had the moon, the sun, the sky or the sea or the stars at this moment, I would give all of it to you, my love,” it said. “The only thing at this moment, what I have is my love and my heart and many kisses to give you forever, my love.”

The Shafias checked out of the Days Inn on June 29, 2009. A surveillance camera in the lobby recorded Hamed paying the bill for both rooms (in cash, of course). It was 8 p.m. by the time the cars steered onto the highway, just another part of the master plan. Leaving so late would ensure that the victims were sleeping, or at least groggy, when the ambush came.

According to the prosecution’s version of events-the story the jury ultimately believed-this is what happened next. With the Lexus in the lead, Hamed at the wheel, the caravan drove east along the Queen Elizabeth Way, Sahar thumbing message after message. 7:59. 8:03. 8:07. 8:10. 8:26. Approaching Toronto, they took a scenic detour, heading downtown. At 9:39 p.m., from inside the Nissan, Sahar took a picture of the Rogers Centre. Three minutes later, she snapped a night shot of the CN Tower. The cars steered north onto Yonge Street and up through the city, turning east on Highway 401. As the clock approached 10:30 p.m., they stopped at a roadside McDonald’s in Ajax. During the bathroom break, Tooba had a brief conversation, less than two minutes, with another one of her brothers (who cannot be identified). He was worried, it seems, checking to make sure Shafia had not followed through on his homicidal threats.

At 10:54 p.m., as the cars pressed on, Sahar received another call from a friend. They spoke for 37 minutes. It was the last time she answered the phone or replied to a text.

The cars coasted through the darkness, past Trenton, past Belleville, past Odessa. By now, prosecutors believe Shafia was behind the wheel of the Nissan, driving the doomed. They went right past all the major exits for Kingston, the ones full of signs for hotels and fast food. At Highway 15, the city’s final off-ramp, they turned north and steered toward the locks. It was almost 1:30 in the morning. At 1:36, Sahar’s phone received its last text message above ground. It was from Sanchez.

As the killers predicted, the Nissan passengers were in various states of sleep as they pulled into the Kingston Mills parking lot. Shafia got out of the Nissan. Tooba got in.

It was her job to stay with the four corpses-to-be while her husband and son went “looking” for a motel. The girls would have no reason to be suspicious. No reason to run. They were with their mother, after all. If Tooba wrestled with any second thoughts, an urge to warn her daughters about their impending execution, she fought it.

Five minutes away, at the Kingston East Motel, Shafia and Hamed woke up the manager. They needed two rooms for the night. When asked how many guests were staying, they seemed confused. Six? Nine? They settled on six. Hamed handed over the cash.

After dropping off the other three children (“A,” “B,” and “C”), Shafia and Hamed drove out of the parking lot, turning left toward the locks. When Tooba saw their headlights in the distance, she jumped out of the Nissan and ran toward them. The time had come.

The exact location remains a mystery, but somewhere at that secluded lock station, the four women were held underwater, one by one, until they stopped moving. Three of them (all but Sahar) had bruises on the top of their heads, suggesting some kind of blow in those final moments. Dead, or at least unconscious, the bodies were piled back inside the Nissan, the front seats reclined.

The idea was to stage a traffic accident, to convince the cops that they were dealing with a tragic, late-night joyride. But as one of them drove the car to its final resting place, doubt must have crept in. Just to reach the water’s edge, the Nissan had to jump a high curb, drive across some grass, make a hard left around a rock outcropping, then a quick right around a narrow wall. The route looked nothing like a split-second wrong turn.

Once in position, the driver left the engine running, got out, reached through the open driver’s side window, and moved the gear shift into first-assuming, on its own power, that the car would plunge over the concrete lip and into the water. It didn’t happen.

The front wheels went over the ledge, but nothing else. The car teetered in the night, tires spinning, engine running, four bodies inside. The plan, flawed from the beginning, was now in crisis.

One of the three reached through the window and turned off the ignition. But the bigger problem remained, dangling in plain sight. Red-handed, they had only one choice: drive the Lexus behind the car, and ram the dead the rest of the way.

The collision shattered the SUV’s left headlight, leaving bits of plastic scattered on the ground. Before speeding away, the killers scrambled to pick up each of the broken shards. They didn’t get them all.

Chapter 6: A cover story collapses

Hamed did call the police that morning-from Montreal. At 7:55 a.m., just hours after the Nissan sank, he reported a single-car fender-bender in an empty parking lot near their house. He told the responding cop that he accidentally smashed the left front end of the Lexus into a yellow utility pole.

At 8:30, he phoned the Kingston East Motel and spoke to his father. Then he dialled Sahar’s cell, knowing full well it was submerged in the canal; when the call went straight to voice mail, he phoned again. By then, Hamed was behind the wheel of the family’s green Pontiac minivan, speeding back to Kingston.

He was in such a rush to switch the cars-and stage a bogus accident-that he took everyone’s luggage, including his mother’s purse, with him to Montreal.

Back at the motel, Hamed and his parents dropped the other children at a nearby Tim Hortons and initiated the next phase of their plan: the missing persons report. They walked into police headquarters just after 12 o’clock.Hamed, if not all three, had been awake the entire night.

At the locks, investigators were already combing the scene, alerted to the sunken sedan by a Parks Canada employee earlier that morning. It didn’t take long for police at the station to make the connection. Escorted into a private room, the trio was told what they already knew: their relatives were dead, discovered in a bizarre, watery grave.

If Shafia shed any tears at the news, they were gone by 3:45 p.m., when he sat down with Det.-Const. Dempster for his tape-recorded interview. Composed and coherent, he talked about his business interests overseas, the $2-million shopping mall in Laval, and Zainab’s pending engagement plans. “It wasn’t a hundred per cent,” he explained, his Dari answers translated by a Farsi interpreter (Farsi and Dari are essentially the same, like British English and American English). Shafia also mentioned, without being asked, that his kids liked to “turn on the car and take it away.”

He said they stopped in Kingston early that morning because his wife, driving the Nissan, was feeling “dizzy” and needed to sleep. So she waited-with the “ones who are no longer”-while he and Hamed went searching for a place to sleep. When the Nissan rejoined them at the motel, Hamed left for Montreal “to work on the building or something” and everyone else went to bed. And that’s when Zainab and Sahar asked for the keys to retrieve some clothes from the trunk.

Gentle but pressing, Dempster kept returning to a portion of the story that, 21Ž2 years later, was a key sticking point at trial. Where did Tooba wait while the Lexus looked for the motel? And how did she know where to meet them afterwards?

The truth, of course, is that the Nissan waited at the locks parking lot-and never made it to the motel. But in order to sell their dubious story-that Zainab, with no licence and no permission, took the car for a deadly spin-they had to tell the police that it did get there. So when Dempster asked the obvious question (where did Tooba wait for the Lexus?), Shafia couldn’t tell him the truth because it was the precise spot where his daughters died.

“I don’t know the place, exactly, because I am not familiar here,” he said. But it was somewhere in the city, he said, not off the highway. “From there we got the hotel, my wife arrived to the hotel, we stopped the car, and there was nothing else.”

“How did your wife know which hotel to go to?” Dempster asked.

“You know, the distance was little,” he said.

Still puzzled, Dempster asked another obvious question. “What do you think happened, Mohammad?”

“I just woke up in the morning and didn’t see them, that’s it,” he answered. “I don’t know anything else.”

“You know the car, your car, the Nissan, was found underwater,” he continued.

“You said it,” Shafia answered.

“Any thoughts, any idea, how it got there?”

“No, no, no, not at all,” he said. “Because this is the first time such an incident has befallen me.” As he left the interview room, Shafia checked his watch.

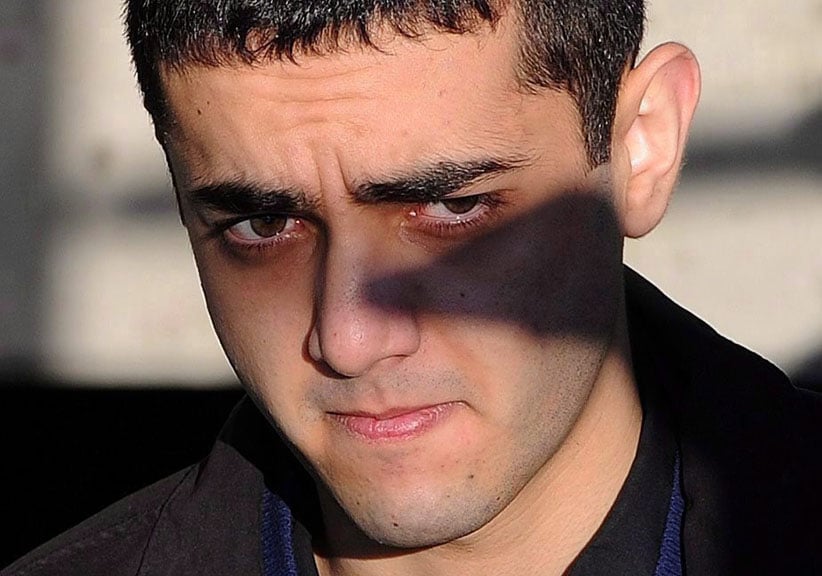

Hamed did not need the interpreter. Fluent in English and Dari, he looked like any other 18-year-old Canadian, with Air Jordan warm-up pants and a mop of curly black hair. When Dempster asked if he wanted some tea or coffee, he replied: “Oh no, it’s all good.”

Dempster asked Hamed the same question he asked his dad: where did Tooba wait with the Nissan? “I think it was a McDonald’s or something,” he said. “I’m not sure.”

Once they reached the motel, Hamed said he plopped on a bed for a few minutes, just long enough to hear Zainab ask for the keys. Then he and the Lexus left for Montreal.

Why Montreal? Hamed’s reasons ranged from “something personal” to “I forgot my laptop” to sometimes “you don’t feel like staying at one place with your parents, ya know?” Each new response only made Dempster that much more suspicious.

“Hamed, do you know what happened to your sisters?” he asked, point blank.

“No.”

“You don’t?”

“No.”

Still doubtful, Dempster told Hamed about an eyewitness (an eight-year-old boy, it turned out) who had just spoken to an investigator on scene. According to his story, there were two cars at the water’s edge, but only one-the bigger one-drove away.

“You mean someone pushed them in?” Hamed asked.

Up until that point, Dempster had never suggested such a scenario. “Hamed, I think you know more than what you’ve told me here today,” he continued.

“I have no idea,” Hamed answered. “You mean someone must have, uh, uh, together? Must have come together with them?”

“I’m not saying that person caused it to happen,” Dempster said. “I’m not saying they did it on purpose, but there is somebody out there that knows what really happened and we need that person to speak up.”

Hamed said he was “shocked” by the suggestion. “If I would have witnessed something, I would be the first person to tell my mom and dad,” he insisted. “How would I feel inside?”

Dempster made it clear he wasn’t accusing anyone of anything. But just to be sure, he said the Montreal police were going to swing by the house and take a peek at the Lexus.

When Tooba took her turn in the interview room, Dempster got right to the point. “What I am trying to understand, and I think what everyone wants to know, [is] how the car got from the motel to the water,” he said.

“Can I say?” she answered.

“Yes, please.”

Tooba said she was the one who steered the Nissan into Kingston, but was too “tired” and “nauseous” to go any further. She parked (somewhere) and waited for the others to find a place to sleep. “When they got the motel, they wanted to come to get me,” she explained. “But I came myself.” She was changing for bed, around 2 a.m., when Zainab walked in and asked for the keys. “I don’t understand what happened after that.”

Tooba-three daughters dead, her life supposedly destroyed-told her story as if only the car was lost. No tears. No emotion. But she did make sure to point out that her eldest daughter was in a “hurry” to get back to Montreal. Tooba even claimed that Zainab-who, again, didn’t have a licence, let alone highway experience-was begging to drive during the trip back from Niagara Falls. “She would do whatever she wanted to do,” Tooba said. “I think she thought: ‘My mom and dad are asleep, let’s go for a drive and return.’ “

“Were you there when the car went in the water?” Dempster asked, a few minutes later.

“No, no, I wasn’t there,” she said.

“If you were not there, my job is to find out what happened, and tell you,” he continued. “As a parent, one parent to another, if something happened to my child, I would want to know the truth.”

Tooba nodded in agreement. “I would have told you everything, but I haven’t seen anything,” she said. “If I knew I would have told you, and you could have helped me.”

Dempster leaned in closer. “People have not been truthful with us today.”

At 8:40 p.m., the sun setting over the crime scene, Hamed was back in the interview room, arms folded. As promised, an investigator had contacted the Montreal police-and Dempster now knew about the single-car smash-up that morning. “Why are you hiding that information from me, Hamed?”

His answer was immediate: “If I would tell you, you would go tell my dad.”

Hamed said he was on his way to grab some breakfast when he accidentally smacked the pole, and just didn’t want his father to find out until after everyone got home. “I don’t know where you’re going with this, honestly,” he said. “I didn’t chase her, man.”

“Did your dad?” Dempster asked.

“No.”

Why were the girls cruising around the outskirts of Kingston at 2 o’clock in the morning? Were they hungry? Scared? Sneaking back home? “I don’t know, ya know?” Hamed said. “I want to find this out as much as you.”

Out of questions, Dempster left Hamed alone in the interview room. For seven minutes, the camera still rolling, the 18-year-old got a preview of life inside a small space. He flexed his biceps, flipped through his wallet, and picked his nose.

In Montreal, Ricardo Sanchez was dialling his phone, desperate to reach Sahar. He would call her number 22 times over the next three days, each attempt forwarded to voice mail.

Chapter 7: Wails and wiretaps

Sahar’s white body bag-#0000200-was the first on the autopsy table. Dr. Christopher Milroy had been briefed on the basics (Niagara Falls, submerged car, open window) and as he examined the young corpse in front of him, he filled his clipboard with meticulous notes. The memory stick in her pocket. The belly button ring. The potatoes in her stomach, most certainly french fries from that Ajax McDonald’s. Sahar was “a well-nourished and well developed female,” he concluded. “There were no fresh injuries.”

Rona, like all of them, had “washerwoman hands,” wrinkled like prunes after so long in the water. Her eyes were brown, her hair was black, and her heart was the heaviest of the four: 300 g. On page eight of his report, Milroy noted-oblivious to the full significance-that Rona was “non-pregnant.”

It wasn’t until Dr. Milroy peeled back the skin on her skull that he discovered the red and black bruises. Both were on the crown of Rona’s head, covering six centimetres in diameter. “It is a very substantial area of bruising,” he said. “It could occur in one impact or it could be the result of two impacts.”

Geeti, third on the table, had nearly identical bruises on her head, though smaller. So did Zainab. “It is unusual that all three would have similar injuries,” the pathologist testified. “It clearly requires explanation.”

That explanation would never come. Science could confirm only three things for sure: the head injuries occurred while the victims were still alive (the dead can’t be bruised), the official cause of death was drowning, and there were no drugs or other paralyzing substances found in the women’s blood. Were they knocked unconscious before the water filled their lungs? Did they actually drown in the canal, or somewhere else beforehand? Were they dead or alive when the Nissan sank? As Milroy put it, “the pathology is neutral.”

But outside the autopsy room, investigators were piecing together other important clues-literally.

The day the bodies were found, while Hamed was dodging questions about his parking-lot “accident,” an observant constable named Rob Etherington noticed something near the locks: tiny shards of plastic, seven pieces in all. The next afternoon, with Shafia‘s permission, Det. Steve Koopman drove to Montreal to see the mysterious SUV with his own eyes. In the trunk, he found more broken bits of plastic, these ones obviously from the dented front end (which, of course, Hamed blamed on the yellow post).

It was Etherington, examining both bags of plastic, who made the stunning connection. Each fragment-the ones from the locks, and the ones from the Lexus-fit together like a puzzle. Clearly, the Nissan had not been alone that night.

The investigation, just 72 hours old, was now a homicide file.

For the suspects, like their victims, things unravelled at a furious pace. While Shafia and Tooba were granting tearful interviews to the media, detectives were quietly learning the truth about life inside their home. The 911 calls. The child welfare complaints. Zainab running away. Rona’s true identity. Fazil Javid. Latif Hyderi. Honour. When investigators seized the Lexus on July 10, they found two curious photographs inside the console; both were of Sahar’s boyfriend. A week later-just 17 days after the women died-a judge authorized the use of wiretaps.

In a classic ruse, police invited Shafia, Tooba and Hamed back to Kingston on July 18, supposedly to return some belongings and update them on the investigation. While they were inside the station, cops in the parking garage bugged their minivan. Before sending them home, officers also took the family on a tour of the locks-telling them, falsely, that a camera had been found nearby and detectives were poring through the footage. When the trio climbed back in the van, police were eavesdropping. “They’re lying,” Shafia said, in Dari. “If there was a camera they’d access it in a minute.”

Tooba agreed. “There was no camera over there,” she said. “I looked around, there wasn’t any. If, God forbid, God forbid, there was one in that little room, all three of us would have been recorded.”

Hamed was driving, the engine humming in the background. “That night there was no electricity there, everywhere was pitch darkness,”Shafia said. “You remember, Tooba?”

“Yes,” she answered.

At one point, Hamed actually warned his parents that police “can fasten something to record your voice.” They kept talking anyway. “To hell with them and their boyfriends,” Shafia said. “Filthy and rotten children.”

Over the next three days, police would record Mohammad Shafia cursing his dead daughters and basking in their demise. He was a good father, a “liberal” who “took on drudgery for them.” And yet they “betrayed” him, “undressed themselves in front of boys” and acted like “whores.” “If we remain alive one night or one year, we have no tension in our hearts, [thinking that] our daughter is in the arms of this or that boy, in the arms of this or that man,”Shafia railed, during another ride in the van. “God curse their graduation! Curse of God on both of them, on their kind. God’s curse on them for a generation! May the devil s—t on their graves!”

His primary complaint, repeated over and over, was that Zainab defied tradition. If she wanted to get married, they would have found her a proper khwastgar (suitor). “You and I both were trying to find a good person to give her away to,” he told his wife. “We weren’t going to keep her for ourselves! That wouldn’t have been an appropriate thing.”

During another conversation, on July 20, Tooba agreed that Zainab “was already done,” but wished the “two others” (Sahar and Geeti) were not. “No Tooba, they messed up,” Shafia said. “There was no other way . . . They were treacherous. They betrayed both themselves and us-like this woman standing on the side of the road, and if you stop the car, she would go with you anywhere. For the love of God, Tooba, damnation on this life of ours, on these years of life that we lead! When I tell you to be patient, you tell me that it is hard. It isn’t harder than watching them every hour with boyfriends. For this reason, whenever I see those pictures, I am consoled. I say to myself: ‘You did well. Would they come back to life a hundred times, for you to do the same again.’ That is how hurt I am.”

Police had heard enough. The next afternoon, July 21, officers arrived at the Shafia residence with a search warrant-and child welfare workers. For their own safety, “A,” “B” and “C” were removed from the home and placed in protective care.

Amid the commotion, detectives made sure to hand Hamed a copy of the warrant, which listed all their names and the exact offence under investigation: four counts of first-degree murder. “We wanted him to read it,” Dempster explained. “We wanted to hear what they had to say to each other when presented with the fact that we believed they had committed the murder of their family members.” Again, the tactic worked.

“My conscience, my God, my religion, my creed aren’t shameful,”Shafia told the others, back inside the van. “Even if they hoist me up onto the gallows, nothing is more dear to me than my honour. Let’s leave our destiny to God and may God never make me, you or your mother honourless.”

“There is,” he said later, “no value of life without honour.”

Detectives spent hours inside the house, cataloguing and seizing potential pieces of evidence. Phone bills. Passports. A pink photo album with Disney characters on the cover. Rona’s diary. The laptop. Hamed’s black suitcase, still packed with the pictures of Sahar that he took to Dubai to show his dad. In Hamed’s bedroom, police also found a handwritten essay-“Importance of Traditions and Customs”-penned for a recent school assignment. “Traditions and customs are to be followed till the end of ones life,” he wrote, the mistakes marked by a teacher’s pen. “It doesn’t matter at all weather your close to the community following the specific traditions or living millions of miles away. Traditions and customs of a person is like his identity and what makes him special.”

When police left, the Shafias were allowed back inside. What had been a family of 10, then a family of six, was down to three. “Oh God, what kind of disasters have you brought over me,” Tooba said, walking through the house. “Oh God.”

The wiretaps were still rolling at 2:56 a.m., when Hamed’s cellphone rang. On the other end of the line was his little brother. “Look, Hamed, you are 100 per cent caught,” he said.

Police interviewed both “B” and his sister, “A,” and made it clear that their mom, dad and brother were responsible for what happened to Rona, Zainab, Sahar and Geeti. “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” Hamed told his brother. “I will tell you this in advance: don’t be shocked when you hear anything.”

Tooba spoke to all three of the children that morning. She told “C,” the youngest, not to cry. She asked “B” for more details about his chat with police. “Are they saying that they have 100 per cent proof or just suspicion?” she asked. And she told “A” that “if God wills, everything will be fixed.”

Loyal till the end, “A” had another strategy. “You should get a lawyer and keep saying: ‘No, we didn’t do it.’ “

Six hours later, they were in handcuffs.

Chapter 8: Shifting stories, twisting lies

“Do you hear their voices?” the police officer asked, sitting beside Tooba in the back of the car. “Do they come to you in your dreams? How many times do you hear their voices?”

“A hundred times in every moment,” Tooba sobbed.

“Aren’t they telling you: ‘Mommy, we were innocent’?”

“They come into my dreams, but the following morning I forget,” she replied. “I don’t know what they said.”

Shafia and Hamed were riding in the back of a different car, also bound for Kingston. “Don’t worry, my son.”

“I’m not worrying,” Hamed answered. “Only about my mother.”

“It’s okay, my son.” Shafia urged his boy to drink some water. “We haven’t done anything wrong,” he said. “They did it themselves.”

Among the officers waiting at police headquarters was Insp. Shahin Mehdizadeh, a Farsi-speaking Mountie based in British Columbia. A veteran of major crime investigations, he was parachuted in for the sole purpose of interviewing husband and wife in their native tongue. But before entering one of the interrogation rooms, he watched Tooba on the monitor, her tear-soaked face buried in the pages of the Disney family photo album. “I want my children,” she wailed. “I haven’t killed and I don’t want to talk.”

By then, all three suspects had been separated. No more chances to talk things over. No more time to plot the next lie. Investigators would grill them for hours, cornering them with the overwhelming evidence and urging them to come clean.

One would crack (sort of). The other two would stick to the story. And then one of them would invent a completely new version of events, hoping to save all three.

“We know what has happened now,” Mehdizadeh told Tooba, his words subtitled for the jury, like a foreign film. “But we want to know why. Why have four lives been lost?”

Why was Hamed’s cellphone in Kingston on June 27, while the rest of the family was still in Niagara Falls? Why did Shafia ask your brother to help him kill Zainab? Why did police find pieces of a Lexus headlight at the scene? Leaning in closer, Mehdizadeh put his hand on Tooba’s shoulder. “When you see the body of your daughters that are cold and dry, is this something that we could forget?” he asked. “Tell me the true story. Open your heart. I know you want to do this because this is the right thing. You are a good Muslim. You want to do the right thing.”

Hour after hour, question after question, Tooba cried and denied and insisted that no mother could commit such an act. But the more Mehdizadeh suggested that her son was a killer, the more her story shifted. “I request you one thing,” she finally said. “Never tell my husband that I have said this.”

She went on to explain that Shafia was “alone” with the Nissan at the water’s edge, and that she and Hamed were across the road with the Lexus. Then suddenly, out of nowhere, they heard a splash.

“Hamed and I ran screaming,” she recalled.

“Hamed went into the water to save them?” Mehdizadeh asked.

“Into the water? No. He couldn’t go into the water.”

“Why?”

“He couldn’t go. We ran and I fell down.”

Tooba said she fainted, and the next thing she knew they were back at the motel.

“These four women are just sitting and looking at each other to go to their graves?” he asked. “It is not possible, madam. If you were in the car, you would come out. You would have opened the door and come out.”

He squeezed Tooba’s hands. He offered to get on his knees and kiss her feet. He told her, over and over, that she needed to act like a real mother. But Tooba would say no more, too tired and confused and impatient to keep talking. “In my view, you are a kind of mother with a heart like a rock,” Mehdizadeh said, his tone shifting. “None of you, none of you have an atom-size discomfort that your children have died.”

“I have,” she said. “Believe me, I have.”

“Madam, if you had, you would have told the truth. You would have wanted to help us. You would have wanted to respect your daughters.”

“I have,” Tooba said. “These are my children.”

“Don’t say ‘my children.’ When you say ‘my children’ my heart gets a little pressured. Nobody wants to see his children get drowned like this and not tell anyone.”

In a nearby interview room, Hamed was slouched in his own wooden chair, flipping through photos of the dead. He had asked-repeatedly-to see them. “They deserve to know the truth,” said Sgt. Mike Boyles, sitting across the table.

“I seriously don’t know,” Hamed said, never lifting his head.

“Look at me,” the sergeant said, swiping away the pictures. “Your father shouldn’t have got you involved in this, or your mother.”

Hamed reached for the photos again, but this time Boyles refused to hand them over. “Why should you get to look at them if you can’t look at me and tell the truth?”

Like Mehdizadeh, Boyles told Hamed exactly what the police had. The headlight. The wiretaps. Zainab’s misbehaviour. “In my opinion, you’re a victim of circumstance, to some degree,” he said. “I’m not going to sit here and tell you your culture is wrong or our traditions [are] wrong. What I’m here to tell you is what you did in Canada is illegal, and now you have to own up to it.”

Even after Boyles told Hamed that his mom placed all three of them at the crime scene, he continued to insist it was all an accident.

“You guys aren’t hit men,” the sergeant said. “You guys don’t know how to cover your tracks properly. You don’t know how to get away with things.”

Hamed asked to go back to his cell.

Shafia spent the night in a different cell, his first of many, before officers took him to the interview room. Dressed in the same slacks and sandals from the day before, he said his arrest was a “violation of his right,” that his life was “ruined,” and that the person who really killed his family “should be found” and punished. “They were pure and sinless kids,” he said. “They were our children.”

Mehdizadeh did not mince words. “I want to tell you that we are certain that you, your wife, and Hamed had involvement in the killing of them,” he said. “You are a wise man. I will prove to you that you had planned this.”

Shafia denied everything. “I wish God would have taken my life and spared their lives,” he said. “I would have been ready.” He wouldn’t even admit that Rona was his wife-despite the wedding photo in the inspector’s hand. “It was her birthday or something,” Shafia said. “This is not marriage.”

Getting nowhere, Mehdizadeh eventually stood up to leave. “A small Nissan car became their grave,” he said, glaring down at his suspect. “Whoever does this, he is a criminal, he is a person who in fact doesn’t have a heart.”

“You are absolutely right,” Shafia answered.

“He is the worst, dishonourable person in the world.”

Remember those words, Mehdizadeh told him. “You don’t have even a little honour,” he said, walking out the door. “The honour of your family is in the hands of your women.”

Four months later, as police continued to investigate, an envelope arrived at headquarters. The Shafia case, twisted enough already, was about to take another astonishing turn.

The package was from Moosa Hadi, a Queen’s University student originally from Afghanistan. Hired as a translator for defence lawyers, he was directing his own private investigation on the side. Convinced that the cops were dead wrong, he wanted the police to listen to a jailhouse interview he had conducted with Hamed just a few days earlier.

In the recording, Hamed revealed much more than he did to Sgt. Boyles. He told Hadi that both cars did arrive at the motel, and that Zainab and the others were inside the Nissan, itching to buy some phone cards. Hamed advised against it, he said, but agreed to follow them in the Lexus just to make sure they made it back from the gas station. “They are scared at night,” he explained.