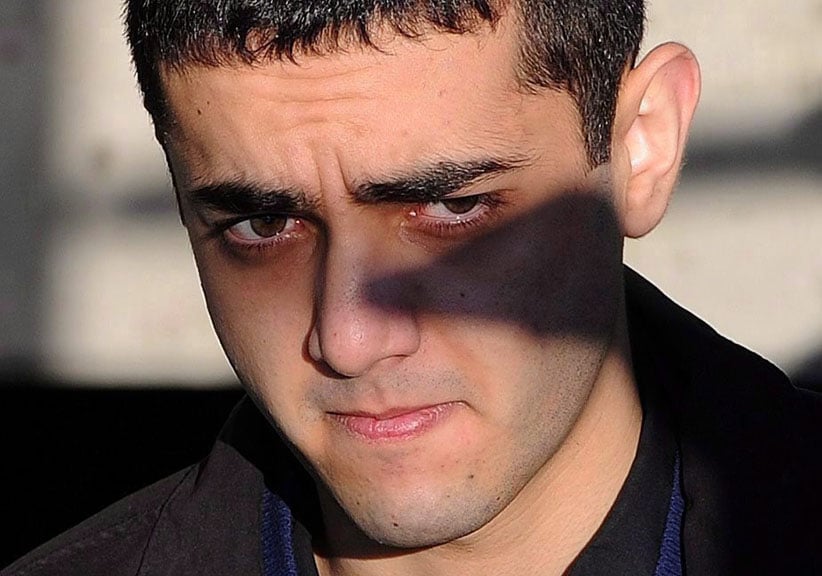

Was Hamed Shafia a teenager when he murdered his sisters?

A closer look at the controversial documents that could win the convicted “honour killer” a new trial—in youth court

A car is removed from the Kingston Locks in this Shafia trial court photo released recently. A court is hearing that the young man accused of killing his sisters saw them plunge into a canal in a car, but didn’t call for help. (The Canadian Press)

Share

A few months after he was arrested—along with his mom and dad, in connection with the mass “honour killing” of four female family members—Hamed Shafia opened up to a private investigator hired by his father. With a video camera rolling during a jailhouse meeting, Hamed admitted, for the first time, that he was present at a Kingston, Ont., lock station when his sisters’ Nissan Sentra plunged into the water.

What did Hamed do when the car went under? What any brave brother would have. He said he grabbed a rope from his Lexus SUV and dangled it in the canal, and when nobody emerged, he promptly drove away. He didn’t dive in to try to save anyone. He didn’t grab his cellphone and dial 911. “I was scared,” Hamed told the investigator, insisting his parents would “blame” him for allowing one of his sisters to drive without a licence. “I decided with myself not to say that I was with them.”

At trial, that was the trio’s defence in a nutshell: Mohammad Shafia and his wife, Tooba Yahya, were nowhere near the locks when the girls perished. Hamed was, but chose not to tell anybody about the terrible “accident.”

The jury ultimately believed the prosecution’s version of events: that three immigrant sisters from Afghanistan (Zainab, 19; Sahar, 17; and Geeti, 13) were murdered by their father, mother and brother because they didn’t behave like good Muslim girls should. Their “treacherous” conduct—secret boyfriends, tight clothes, independent thought—had so shamed the family name that only their deaths, disguised to look like a tragic wrong turn, could restore the family’s tarnished honour. (The fourth victim floating in the car, 52-year-old Rona Amir Mohammad, was Shafia’s first, infertile wife in their secretly polygamous clan.)

Nearly seven years after the bodies were discovered—and four years after the killers were sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years—Hamed is now raising a new claim at Ontario’s Court of Appeal: that he was 17, not 18, when his sisters died, which means he should have been treated as a youth suspect, not an adult. The “fresh evidence application” is at the heart of the Shafia family’s ongoing quest for new trials (along with the claim that all their convictions should be set aside because the Crown’s key witness, a University of Toronto professor who specializes in honour-based violence, tainted the jury with “cultural prejudice” and “pre-existing stereotypes of violent and primitive Muslims.”)

Why did it take all this time for Hamed to suddenly realize that he’s not as old as he thought? Like all things Shafia, the truthful answer is a moving target. “I hope you’ve all brought some Tylenol with you,” joked Scott Hutchison, Hamed’s lawyer, as he addressed a three-judge panel on Thursday.

Here is the supposed chain of events, as outlined in another new factum filed with the province’s highest court: Not long after the guilty verdicts were announced in January 2012, Shafia decided that he wanted to transfer some of his property in Afghanistan to Hamed. From prison, he asked his other son—who can’t be identified because of a publication ban, but who attended Toronto’s Osgoode Hall to watch Thursday’s hearing—to contact an employee overseas to arrange the necessary paperwork. (A multimillionaire businessman when his family of 10 immigrated to Montreal in 2007, the Shafia patriarch remains a wealthy man—although notoriously stingy. His wife’s former lawyer is still suing him for $143,000 in unpaid legal fees from the first trial.)

In Kabul, the factum claims, Shafia’s employee stumbled upon Hamed’s “tazkira,” the main identity document issued by the government of Afghanistan. The date of birth? Dec. 31, 1991—not Dec. 31, 1990, the date stamped on all of Hamed’s Canadian identification. According to the factum, the employee then obtained a “Certificate of Live Birth” from Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health. The birth date was the same: Dec. 31, 1991, which would make him 17, not 18, when he conspired to kill his sisters and stepmother. (A third document from the Ministry of Interior Affairs, which is essentially a translation of the “tazkira,” has also been filed as evidence.)

In his oral submissions to the court, Hutchison told the judges that in Afghanistan, dates of birth don’t hold the same sentimental significance as they do in Canada. Throw in the fact that the Shafias fled the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—moving from Pakistan to Dubai to Australia and finally to Canada—and it’s easy to see how Hamed’s birthday could have been misstated somewhere along the way. “This was a family who fled civil war from a country with non-Western documentation systems and a different cultural understanding of the importance of birth dates,” the factum continues. “Put bluntly, whether the birth years were recorded correctly would, at the time, have been the least of their worries. And attempting to correct any errors would only have impeded their ability to gain entry to the next country they journeyed to in search of a new home.”

When shown the newly discovered documents, the Afghan Embassy in Ottawa provided perhaps the biggest boost to Hamed’s claim. “Taken together, the three documents we reviewed above would constitute sufficient proof of identity,” the Embassy wrote in a letter, now an exhibit. “If an individual were to present themselves at our Embassy with these three documents, we would issue them an Afghan passport bearing the date of birth of December 31, 1991.”

Hutchison asked the judges to admit the fresh evidence and order a new trial in youth court. In the alternative, he wants his client re-sentenced as a young offender. The maximum punishment for a youth convicted of first-degree murder is 10 years in prison; Hamed, now 25 (or 24) has already been locked up for nearly seven years.

Late Thursday afternoon, the Crown began its oral submissions. Their written arguments remain sealed (for now), but their strategy is already clear. “The bottom line is this document is utterly unreliable,” Jocelyn Speyer told the judges, referring to the “tazkira.” As for the birth certificate, it contains no date of creation and no signature, she said. “It’s a document which, on its face, is materially incomplete.”

Before court adjourned for the day, Speyer also pointed out the obvious: that the one person who would surely know exactly when Hamed was born—his mother, Tooba Yahya—is silent on the issue. Her voice is not among the numerous affidavits filed in support of the fresh evidence application.

When she was talking—to an RCMP interrogator on the night of her arrest—she did mention Hamed’s age. He was 18, she said.

The hearing continues Friday morning.