What the skyrocketing popularity of Beyond Meat means for our planet

The company and its many competitors are normalizing plant-based meat alternatives. But what will this shift mean for the meat industry?

Consumers are hungry for plant-based meats, and they’re putting their money where their mouth is to the tune of US$888 million (Photograph by Christie Vuong)

Share

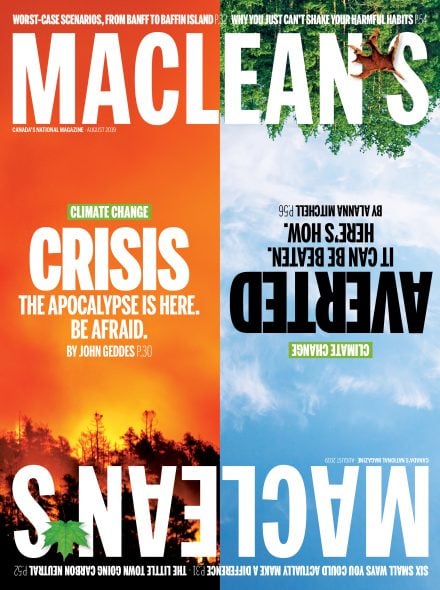

This article is part of a special climate change issue in advance of the federal election. This collection of stories offers a comprehensive look at where Canada currently stands, what could be done to address the issue and what the consequences might be if this country continues with half measures. Learn more about why we’re doing this.

In the mid-2000s, the Los Angeles-based entrepreneur Ethan Brown was working as a high-level manager at Ballard Power Systems, one of the world’s leading hydrogen fuel-cell companies. It was a good job, and the company did pioneering work, creating clean energy solutions for the transportation and power generation sectors. But over time, Brown, a vegan who had grown up partly on a farm in Maryland, started to notice a disturbing disconnect. Every day, his colleagues were figuring out ways to combat climate change; every day, they were also eating meat. It was habitual and reflexive; they didn’t really think about it all. Nor did Brown, until he learned the extent that meat production contributes to a warming world. According to recent research, meat and dairy use 87 per cent of farmland and produce 60 per cent of agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions, yet provide just 18 per cent of our calories and 37 per cent of our protein. Raising animals for food is also extremely inefficient, requiring five to seven kilograms of grain to produce one kilogram of beef. “From a climate perspective, there is nothing more urgent than tackling this protein problem,” Brown says. He quit his job at Ballard and in 2009 launched a startup with exactly that mission. He called it Beyond Meat.

READ: The climate crisis: These are Canada’s worst-case scenarios

Maybe you’ve heard of it? Earlier this year, the company went public, with the best-performing IPO in 20 years and an eventual US$4-billion valuation. Its investors include Bill Gates, Leonardo DiCaprio and conventional meat giant Tyson Foods. A roster of celebrities have endorsed the firm, including Jessica Chastain, Snoop Dogg and a whole squad of NBA stars: Shaquille O’Neal, Kyrie Irving and Chris Paul. Beyond’s signature plant-based protein patty, the Beyond Burger, debuted in Canada a year ago at A&W restaurants and immediately sold out (customers bought 90,000 burgers in the first three days). A simulated ground beef, also derived from vegetables, appeared on Quesada menus earlier this year, with the taco and burrito chain similarly unable to keep up with initial demand. In February, A&W introduced a Beyond sausage breakfast sandwich and last month, Tim Hortons started selling its own similar sammies (one with cheese and egg along with a vegan lettuce-and-tomato only version). Long available in most American grocery store chains and in fast-service restaurants like Carl’s Jr. and TGI Fridays, the Beyond Burger made its first appearance in Sobeys meat cases in April. It is now available at Longo’s, Loblaws and Metro across Canada.

But Beyond is the best-known of a whole new wave of deceptively meat-like veggie burgers that have captured consumers’ imaginations and taste buds. U.S. sales of plant-based meats jumped 42 per cent between March 2016 and March 2019, to a total of US$888 million, according to Nielsen. “Plant based-dieting has been socially normalized more so than ever,” says Sylvain Charlebois, a Dalhousie University professor who researches food distribution and security. Beyond’s biggest rival, the soy-based Impossible Burger, is still not sold in Canada, but has similar market penetration in the U.S. Most recently, the company partnered with Burger King on an Impossible Whopper so close to the real thing it fooled even the chain’s franchise owners. In the wake of the Beyond and the Impossible, several other similar burgers are either now available or will be soon, their near-identical names collectively suggesting an inspiring new roster of seven dwarfs, including the Awesome, the Incredible (from Nestlé-owned subsidiaries in California and Europe, respectively) and the Undeniable (from Loblaws). Unlike the more faddish, short-lived McDonald’s veggie burger of yore, there are a lot more of these burgers being produced—and eaten. “What’s changed is the scale of these companies. It’s something we haven’t seen before,” Charlebois says. “To actually sell this product in over 30,000 restaurants and to deploy the product to 3,000 locations on one day is quite impressive.” So impressive that a battle between these fledgling food firms and the industry’s titans is now in full swing.

Mock meat—wheat gluten, or seitan, designed to resemble duck or chicken—has been around for centuries, mainly as a part of Buddhist vegetarian cuisine in China. Plant-based proteins that imitate hamburgers, hot dogs and cold cuts have a more recent history. In Canada, since the mid-1980s, chef Yves Potvin has dominated the industry through his familiar, eponymous Yves brand of tofu dogs, ground round and deli meats, as well as his more recently formed company, Gardein, which produces a more expansive line of simulated chicken tenders, fish filets and meatballs. (Both companies are now owned by American conglomerates.) But Potvin’s products, as much as they successfully approximate animal proteins, have traditionally been marketed as vegetarian or vegan products for vegetarians and vegans. Only about seven per cent of Canadians identify themselves as vegetarians, however, and only 2.3 per cent as vegans. Beyond Meat and its competitors, in contrast, have their eye on the far larger omnivore or “flexitarian” (semi-vegetarian) market, one expected to grow to 10 million Canadians in the next five years. The current meat market suggests plenty of room for growth. As plant-based meats were exploding, sales of animal meat only rose one per cent—but still totalled US$85 billion. A Beyond Burger has the virtue, theoretically, of satisfying both the craving for a burger and the desire to cut back on meat consumption. So Beyond and its competitors have spent many years and a lot of R&D dollars—in Beyond’s case, about US$21 million—trying to make plant-based meat that is virtually indistinguishable from animal meat.

Thanks to beet juice and pomegranate fruit powder, the Beyond Burger has a pinkish, raw hamburger hue and, famously, “bleeds” when cut. Thanks to coconut oil, it sizzles and drips in the pan or on the barbecue. Thanks to an array of other ingredients—including pea and mung bean protein, potato starch and apple extract—and top-secret production alchemy, it has a texture that’s as juicy and chewy, even gristly, as your average fast-food burger. The latest iteration of the burger—Beyond releases a new version almost every year—promises even more beef-like “marbling.” It is also nutritionally comparable to beef, with each four-ounce patty containing 20 grams of protein and 270 calories, but no cholesterol. To further drive home Brown’s point, the Beyond is almost always shelved in the meat aisle of conventional grocers.

READ: Yes, climate change can be beaten by 2050. Here’s how.

Appealing to a more carnivorous consumer is one thing, but Brown has more radical aspirations—he wants to redefine our very relationship to meat, shifting our focus from where protein originates, a chicken or cow, say, to the elements that comprise it. “If you think about the composition of meat, it’s actually five things,” he says, “Amino acids, lipids, trace minerals, vitamins and water. All of that is available to us outside the animal. What animals do is take a tremendous amount of plant material and a lot of water and use their digestive system to convert that to muscle that we then harvest as meat. What we’re doing is starting with the same inputs—plants and water—and using heating, cooling and pressure to produce meat directly from plants. If we’re capable of pulling those amino acids, lipids, trace minerals and vitamins directly from plants, we should be able to successfully transition the human race from using animals to harvest meat.” And that transition, according to a University of Michigan analysis of the environmental impact of the Beyond Burger, is good news for the climate: relative to a beef burger, production of the Beyond generated 90 per cent fewer greenhouse gas emissions, used 93 per cent less land, 99 per cent less water and about half the energy.

Not surprisingly, Beyond has received significant pushback from the meat and dairy industry. In mid-May, the Quebec Cattle Producers Federation launched a complaint with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), arguing that Beyond has no right to advertise its products as plant-based meat. To call Beyond meat—defined by the CFIA as “carcass derived from an animal”—is potentially confusing to consumers, said Kirk Jackson, vice-president of the federation, and opens the door to plant-based products being used as filler in actual meat burgers. Seventeen different American states are currently trying to pass laws that would likewise prevent meat alternatives from being called “hamburger” or “ground beef.” In Europe, where KFC has just launched its own vegan “chicken” burger, and Subway and Pret a Manger are adding vegan options to their menus, the EU’s agricultural committee voted overwhelmingly in April to ban the use of meaty names in reference to plant-based or lab-grown proteins. In London and Paris, veggie burgers may soon be branded, ignominiously, as veggie discs. (The newly elected incoming EU parliament still needs to vote on the ban.)

Other members of the Canadian agriculture sector, however, are far more bullish about the arrival of these new plant-based proteins. AGT Food and Ingredients in Regina is the world’s largest manufacturer of pulse ingredients in the world—peas, chickpeas, mung beans, lentils, etc.—and the flours and concentrates derived from such things. For over a decade, AGT has been supplying these products to a host of major international food companies, including General Mills, Nestlé and Loblaws. And now, to Beyond Meat and its competitors. “From an ingredient perspective today, these companies are still modest users of volume,” says AGT founder and CEO Murad Al-Katib. “They’re just at the beginning of their journey. But the growth rates projected are quite shocking.” The alternative meat market, he says, has an annual growth rate of 7.7 per cent, and the pea protein market, he says, will triple by 2025.

In Al-Katib’s view, the trend is one that Canada is actually driving, as our agriculture moves from cereals and oil seeds toward demand for more high-protein, high-fibre protein and legume crops. “If this is the century of agriculture,” he says, “and many believe it is, then this is Canada’s century. We have water and land that no one else has. We have tens of millions of tonnes of plant-based protein that can meet middle-class demand in Asia. That’s the consumer base we’re going to be servicing—the health and wellness consumer in North America and Europe, and the rising incomes in Asia. If we succeed in linking the Canadian protein highway to the Silk Road in Asia, it will mean billions of dollars of economic benefit to Canadians for decades to come.” The federal Liberals agree. A Prairies-based Protein Industries Supercluster was one of the feds’ business-led innovation initiatives announced in 2018. It brings together academic and industry researchers with a focus on plant proteins, promising more than $4.5 billion in GDP impact over 10 years. Health Canada’s recently updated food guide reflects this enthusiasm, recommending Canadians choose protein from plants more often and plan a couple of meatless meals a week.

Given these trends, Al-Katib is now not just content to produce, package and sell these ingredients. As delighted as he is by the rise of Beyond, he thinks there’s lots of room for improvement in the plant-based protein world, in terms of taste, texture and cost. AGT therefore has an R&D centre of its own in Saskatoon, with six full-time scientists working with client brands on new plant-based formulations and also experimenting with their own line of products. At the recent Institute of Food Technologists show in New Orleans, the company showcased its 100 per cent yellow-pea veggie pasta, as well as a pea-coated cauliflower with a dairy-free buffalo ranch dressing made with fava protein. There was also, of course, their own plant-based burger—made of lentils and fava beans. The model consumer for these products, he says, is his own 17-year-old daughter: “She’s highly intelligent and socially conscious. She wants to know and she wants to know right now where her food came from, what its impact is on the world, and she wants to feel good about consuming that product. That’s the trend that’s driving this whole thing. The kids of this generation grew up with hummus and carrot sticks as a normal snack. It wasn’t potato chips and dip. For them, plant-based burgers are actually desirable.”

You don’t need to tell Michael McCain. The president and CEO of Maple Leaf Foods, Canada’s foremost purveyor of old-school bacon, chicken and sausages, has been watching the rapid growth of plant-based proteins very carefully and, one imagines, with a blend of anxiety and avarice. In 2017, Maple Leaf acquired two American producers of veggie deli meats and sausages, Lightlife Foods and Field Roast. They later became the centrepiece of its new U.S.-based plant protein subsidiary, Greenleaf Foods. In the spring of this year, Maple Leaf announced they would be spending US$310 million to build North America’s largest plant-protein manufacturing facility in Shelbyville, Ind. A few weeks ago, Lightlife released its own Beyond-style burger—which, bucking the trend, is called, simply, the Lightlife burger—distributing to all the major grocery chains and getting them on to Kelseys menus just in time for the restaurant’s Burger Month. All of this plant-based activity was part of the company’s strategy to become the most sustainable protein company on earth, and dovetailed with wider improvements to ingredients in all its products, a reduction in its antibiotic use and environmental impact, and more serious attention to animal welfare.

But McCain, unlike Brown, doesn’t speak in the revolutionary language of startups. He’s not necessarily trying to change the world but protect his market share. “When we started investing in product and category knowledge five years ago,” he says, “we knew that we were intending to make major investments in this. We defined the scope of our business as all proteins and it was clear to us that this was going to be a growth segment. I don’t think we imagined it to be the growth that it’s exhibiting right at the moment. But we were confident even five years ago that it would be a relatively high growth rate.” In mid-June, A.T. Kearney, the global consultancy, published a report claiming that, by 2040, 60 per cent of the meat that humans consume will either be lab-grown or replaced by plant-based meat alternatives. Yet McCain, who considers himself a flexitarian, doesn’t agree. In fact, he has doubled down on conventional meat. Last year, Maple Leaf paid $215 million for the Quebec pepperoni producer Viau Foods. At the same time that the company is building its Indiana plant, it’s also constructing a $660-million chicken processing facility in London, Ont.

“All proteins” is a very large category and McCain is betting that only a very large company, like Maple Leaf, can keep up with the growth in both segments—supply chain and logistics experience going back many decades along with a long-standing brand relationship with consumers. “This is going to be increasingly important as this category goes from a cottage business to a scaled-up food industry business,” McCain says, subtly dismissing his upstart competitors.

But those upstarts can be equally dismissive. “I think it’s very hard for companies trying to beat us to maintain our pace,” Brown says. “You’ve seen companies come out with absolute knockoffs of our product, including ones in Canada. The package is the same, the appearance is the same, but the product experience for the consumer is not, because we’ve already moved past that version. They’re taking something off the shelf, taking it to the lab and trying to reverse-engineer it. That’s fine, because they’re chasing a product that we’ve already moved on from.” The paradox of this protein arms race, however, goes back to Brown’s initial revelation. If you really want people to eat less meat, if you really want to create a sustainable food system, then presumably the more companies in the space, the more alternatives to meat, the better. But none of these companies are non-profits—they don’t just want people to eat less animal meat, they want people to eat their particular brand of plant-based meat. “People are viewing this as a war,” AGT’s Al-Katib says. “There’s a war going on to develop and commercialize products that are going to become the known, dominant brands. With the pace and the risk and return, there’s high stakes here.” Brown knows this all too well, and puts it with characteristic audacity: “I’ve always said that competition is good, as long as we’re winning.”

This article appears in print in the August 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Salvation burger.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.