Why cutting Indigenous revisions to Ontario’s curriculum is a travesty

Ontario has missed an opportunity to tell the full and complicated story of what Canada was, is and can be

Share

Theodore Christou is an associate professor at Queen’s University.

Ontario’s newly elected government has dismissed a plan to revise the province’s social studies and history curriculums to add Indigenous content. There was no reason offered for Premier Doug Ford’s decision.

I was part of the group rewriting the curriculum. I am not annoyed at the Ontario government’s decision for partisan reasons, or for the fact that so many taxpayer dollars that had been spent on rewriting curriculum are now wasted.

As an educator who teaches aspiring teachers, I am aghast because the need to Indigenize curriculum in Canada is not up for debate. The calls from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are not suggestions. When Canadians are called, we must respond. Every single call is formidable, and ignored at our peril.

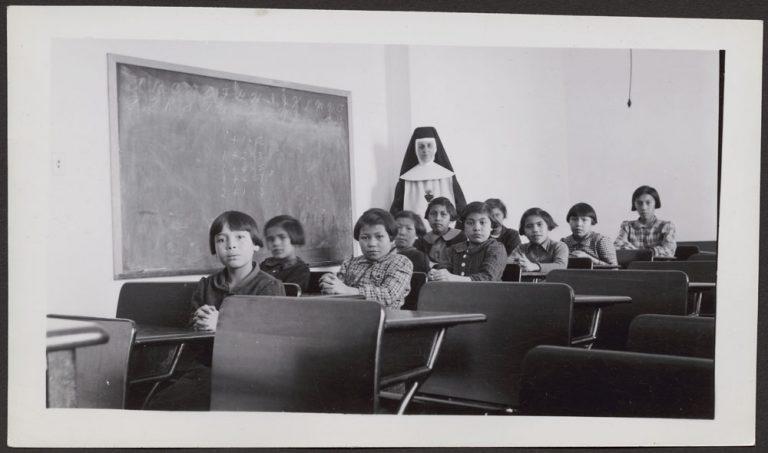

The commission asks all levels of government to consult with survivors, educators and Indigenous peoples on a mandatory curriculum that includes Indigenous history, including the legacy of residential schools. Other provincial governments have undertaken those revisions.

Having the privilege and responsibility to revise curriculum in social studies and history for Ontario meant that I would have had the opportunity to support future teachers’ work in ways that I was not supported as a new teacher.

Learned a lot about European explorers

Let me explain.

A few years ago, as a classroom teacher in Toronto, I was assigned a Grade 6 class. We had three themes in that year’s curriculum: Canada and the World, European Explorers and Native Studies. As a student years earlier, I couldn’t remember learning about the first and third themes, but I certainly remembered hearing all about the European explorers.

Distinctly: Samuel de Champlain founded Québec City in 1608. Before him, Jacques Cartier founded Montréal.. Others, mostly French, founded many things. Henry Hudson has a corporation, a bay and a river named in his honour. It was interesting to learn about the exploits of people who were apparently so intrepid and brave.

Later, I learned that none of this actually happened the way it had been taught to us in school. It was one narrative drawing on particular sources and claims to truth. I was an unlearned student, and later on, an unlearned teacher. I taught as I learned, repeating narratives passed down to me.

Contemplating knowledge, and how we know things, matters. Knowledge is often constructed. This means that we do not inherit narratives, but instead we construct them. Therefore we must question them.

In that vein, Ontario’s social studies and history curriculums have increasingly asked students to inquire about the past, not just to memorize it. There is a big distinction, after all, between repeating a narrative and building a plausible one based on evidence. History education in Ontario is certainly better than it used to be and has been applauded by historians.

New narratives needed

But what evidence and what narratives do we ask students to consider? That’s the question at hand.

The calls of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission mean that we can no longer simply repeat the stories that we have heard and memorized. We must rewrite them with dignity and respect for the peoples that lived in Canada for centuries before the European explorers showed up, colonized and planted the seeds for further colonization.

In our 151st year as a country, social studies and history must be areas of study in which our students explore and question the events that have shaped our past, and what may shape our future. We must question how those events are talked about and taught. If that’s not considered important to Doug Ford and the government of Ontario, I am at a total loss as an educator.

Ontario’s move to dismiss the addition of new Indigenous content as it revises its history curriculum is dangerous. We now have a very narrow idea of what our history is, and we continue to tell students a narrative that is demonstrably and woefully incomplete.

Ontario’s social studies and history students, even as they are encouraged to ask questions about the past, are also taught past one-sided narratives that have gone unchallenged in history books since the foundation of the province’s public school system.

There is now, in Ontario, a missed opportunity to tell the full and complicated story of what Canada was, is and can be. There is less space for constructing knowledge. Memorizing and repeating colonial narratives amounts to the most dangerously dishonest, not to mention boring, history education imaginable.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()