Five shots took Darian’s life. But before that, a justice system failed

Peel police chief Nish Duraiappah expressed frustration at the time for “a complete failure of our justice system to protect her.”

Despite her family’s desperate efforts to

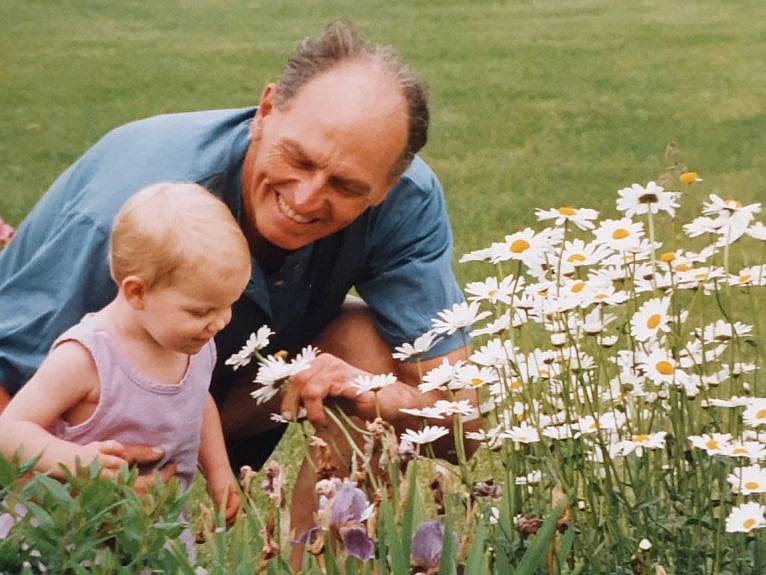

safeguard her, Darian was killed in July 2020 (Courtesy of Michelle Jones)

Share

The shooting death of 25-year-old Darian Henderson-Bellman in Brampton, Ont., last July was a dramatic human tragedy in an otherwise relentless summer of pandemic news. The shots that killed her—five of them in total, brutal and at close range—rang out across the country. For a time the images were splashed everywhere, photos that could have been ripped from a salacious network crime drama: Darian, the pretty smiling woman who grew up in a white clapboard house in Georgetown, Ont. By contrast, her alleged killer: Darnell Reid, 27, who had an illegal firearm, an assault charge and whom police believe shot her then turned the gun on himself in an unsuccessful suicide attempt. On the surface, the story of Darian’s death looked predictably familiar, but like all killings, the truth is far more complicated.

Darian Henderson-Bellman’s death would undoubtedly have made headlines at any time, but in the summer of COVID it caused a national outpouring. The news stories detailed Darian’s attempt to break free from a toxic relationship, as well as Reid’s history of abuse, an illegal weapons charge and four broken no-contact orders. Much was made of his various bail hearings, including the fateful one, at a Milton, Ont., courthouse in late May, at which he was ordered to leave prison and wait out his charges (for possession of a loaded firearm, oxycodone and assault on Henderson-Bellman) on house arrest due to the pandemic.

EDITORIAL: The story of Darian Henderson-Bellman

There were plenty of opinions about who or what, apart from her alleged killer, was to blame for Darian’s death. But none so striking as that of Peel police chief Nish Duraiappah, who, in the days after the killing, released an extraordinary statement expressing his profound personal regret. “The sadness I feel for the victim and her family is mixed with frustration for a complete failure of our justice system to protect her,” he said, adding, “We need to do better.” Police, he emphasized, had done everything they could to incarcerate Reid—his release was a decision made by the courts. At the time, the mayor of Brampton echoed the chief’s sentiments but went one step further, calling for bail reform and stricter penalties for criminals caught with illegal firearms.

Victims’ rights groups and femicide activists were equally outraged; many held up Darian’s death as proof that intimate partner violence was an epidemic not just in Peel region but the rest of the country, too. Ontario’s Domestic Violence Death Review Committee reported at the time that women like Darian are most at risk of being killed when they are leaving an abusive relationship. Between 2003 and 2018, two-thirds of intimate partner homicides involved a fractured or failing relationship. W5 ran a two-part series on the case, casting it as part of a wave of domestic violence against women and featuring in-depth interviews with femicide experts as well as Darian’s grandparents (her legal guardians from a young age), and her birth mother, who spoke of the abuse Darian had endured in the months leading up to her death.

All of these interpretations hold some truth, but lost in the flurry of the initial coverage was the why: why did she end up alone with her abuser, and why was he not still in prison after all that had happened? There were clear and obvious warning signs before Darian’s death, but they did not go ignored—her family, friends, police and others did the best they could to protect her given the circumstances. That they couldn’t in the end is a tragedy with personal and policy implications that will reverberate for years to come.

***

There was only one assessment of Darian’s death that made any clear sense on its own. It’s an interview that Paul Henderson and Flo Bellman, the paternal grandparents who adopted and raised Darian, gave to Global TV in the raw days after Darian’s killing. They are standing on their lawn in Georgetown. Flo’s face is crumpled with grief. Paul stands beside her, arms folded over his barrel chest. He holds up a finger and stabs it at the reporter’s microphone: “You know if it weren’t for COVID-19, she wouldn’t be dead.”

He’s almost certainly right. The courts last year were under enormous pressure to take exceptional measures to do what they could to prevent the spread of the virus in prisons. So, despite all the warning signs, despite a history of violations, despite the illegal weapons charge, the courts released Reid. This single decision was another key factor that sealed Darian’s fate, though it’s impossible to know on precisely what grounds it was made. The documents for Reid’s bail hearing are under publication ban until the trial.

Sociologists have a term for unforeseeable, socially disruptive events like COVID-19 or natural disasters, earthquakes, civil uprising and war. They are called “exceptional events.” There has been little solid data collected on the impact of the current pandemic on crime rates, and what scant data there is has not yet been analyzed in a granular way. Broadly speaking, lockdown caused a drop in violent crime, not just in Canada but across the globe. But while overall crime rates dropped, the statistics on intimate partner violence show a more complicated picture: shelters and helplines across the country report a sharp anecdotal increase in demand for services. And Statistics Canada data collected from 17 police forces across the country show that calls related to domestic disturbances—which could involve anything from a verbal quarrel to reports of violence—rose by nearly 12 per cent between March and June of 2020 compared to the same four months in 2019. But, like the killing of Darian Henderson-Bellman, the question of what transpired behind closed doors during the pandemic is more complicated than it might seem on the surface.

Darian wasn’t trapped at home with her abuser. She went to him in the end. The reasons why are a painful puzzle—including fear for herself and her family—that her grandparents, police and the Crown have spent months attempting to put together. This may explain why the pace of the case, even in court terms, has been glacial. Reid was charged with first-degree murder seven months after the incident. He is now in the Maplehurst Correctional Complex and has been denied bail.

His lawyer, Gavin Holder, said in a May interview he has yet to receive disclosure of the evidence from the Crown; Holder declined to respond to follow-up questions. “In order to make full answer and defence, my client needs to know the case against him. It is concerning that after all this time we are still waiting,” he said in May. “Any claims regarding how injuries were sustained have to be substantiated by evidence and tested in court. So I believe it is dangerous to make any assumptions prior to that point. Remember, my client is entitled to the presumption of innocence that remains with him until the Crown can establish his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt in court.” Reid has not been convicted of any of the charges he faces.

Darian, on at least two occasions, had also broken the no-contact orders put in place for her own protection. What’s more, witness accounts indicate Darian went to Reid’s house voluntarily the day she died. In this sense, Darian’s story is not unusual—abuse victims routinely go back to their perpetrators repeatedly in the hope of effecting a different outcome. After months of violent physical and emotional abuse, her choices had been taken from her.

The exceptional event in this crime is the pandemic itself: COVID-19 was the reason Darnell Reid was released.

***

Georgetown and Brampton sit cheek by jowl on the northwest edge of Toronto’s sprawling commuter belt. Darian grew up in Georgetown, a small town with a storybook main street surrounded by a few leafy blocks of fastidiously maintained Victorian houses. Brampton, by contrast, which Reid called home, is a sprawling, culturally and economically diverse mini-metropolis in its own right.

Darian was born on Jan. 12, 1995, the oldest of five, though the other children were half-siblings she would barely know and never live with. Her parents, Michelle Jones and Conrad Bellman, were both still teenagers, high school dropouts who’d hooked up briefly the previous year. As a newborn, Darian lived with her mother and spent weekends with Flo and Paul in Georgetown.

At first, Flo took Michelle under her wing. Both women were determined to make the best of things. Flo taught Michelle how to feed and burp and change her daughter. She showed her how to soothe the baby when she cried. In spite of this support, teenaged Michelle struggled to cope. Increasingly she was resentful of Conrad’s freedom. One day she carried her infant daughter into a Brampton bar where Conrad was playing pool and handed her over with a bottle of formula. “Your turn,” she reportedly said, then walked out. (“Fair enough,” Flo remembers thinking.)

Conrad made a stab at teenage fatherhood, but ultimately it was decided Darian should live with Flo and Paul. This care arrangement went on until Darian was a toddler. Relations with Michelle were fraught with conflicts over missed visits and practical concerns. Eventually, Flo and Paul, exhausted from all the drama and concerned about Darian’s well-being, decided to sue Michelle for custody on the grounds she was an unfit mother. With Conrad’s support, they won the case, making them Darian’s legal guardians.

Darian was an angelic child with long blond curls and a sweet, pliable temperament. After the custody case, Flo and Paul sold their retirement condo and bought a house on a quiet street in Georgetown. Now that Darian was their daughter, they wanted a big backyard for her to play in after school. While Flo and Paul raised their adopted child in Georgetown, her birth parents continued to struggle down the road in Brampton. Within a few years, both had succumbed separately to crack and opioid addiction.

When Darian was 17, Conrad died after taking drugs and aspirating on his own vomit. The family was devastated. While Darian did not live with her birth father, she saw him most weekends and considered him a big brother. After his death, she had his name and death date tattooed on her inner arm. Flo and Paul donated a local park bench in Conrad’s name; Darian, they say, would often go and sit there alone for hours. Now there is another plaque, with Darian’s name on it.

By the time Darian was in high school, Michelle had given birth to two more children who were subsequently removed from her care. She was, by her own admission, living on the streets of Brampton, teeth rotten, body wasted down to 80 lb. from years of heavy crack and opioid use. Occasionally she tried to make contact with Darian, but for the most part her daughter wanted nothing to do with her. In her teens, Darian asked Flo and Paul if she could change her name from Bellman-Jones to Henderson-Bellman. They agreed.

Flo is a winsome, fair-haired Englishwoman who immigrated to Canada in her early 20s. An avid gardener and reader of classics, she is also a great talker—during our series of interviews, a burbling stream of anecdotes, memories, laughter and anguish flows from her lips. On occasion, Paul gently squeezes her arm, which prompts Flo to pause and say brightly, “Oh wait—Paul wants to say something.”

Before retiring, Flo managed the antiquarian bookstore in Glen Williams, a village near Georgetown. Her husband is a retired printer with a passion for classic cars. He has a big bald head that shines like a polished apple and an earring that makes him look like a pirate. Occasionally, when speaking of Darian’s death and the painful months that precipitated it, Paul gets slightly heated and his voice chokes with anguish. He looks embarrassed afterward, apologizing as for a slip of table manners.

Flo and Paul’s daughter grew up to be a funny, sociable, strong-willed girl. She was also a startling beauty with a winning, easy smile and wide-set blue eyes. Darian was popular in school but languished academically, dropping out by her late teens like both her parents had.

Despite her amiable nature and fragile looks, a rebellious streak emerged in her teens. She clashed with Flo and Paul over school and curfews and smoking, and once or twice left home to live with friends. But she always came home in the end.

By her early 20s, Darian seemed to have found her groove. She started working in retail and moved in with her boyfriend. The couple were deeply in love and described each other as “soulmates.” They had regular family dinners with Flo and Paul, who assumed they would marry.

***

It was around this time that Darian resumed contact with her birth mother, Michelle. Toward the end of Jones’s chaotic, crack-addled years on the streets in Brampton, she gave birth to two more sons. This time she was determined to keep them. She settled in the small town of Listowel, Ont., two hours west of Brampton. She joined a methadone program and attended regular drug counselling. She understood it was her last chance. In an interview, Michelle tells me she’s been off street drugs for five years and completely sober for 18 months, having successfully weaned herself off methadone. She works as a house cleaner these days, fitting her hours around her boys.

Michelle describes her reunion with Darian as the ultimate reward for her hard-fought battle against addiction. “As soon as she saw how much better I was, she forgave me. There was no hesitation,” she says. “That’s what Dare was like. She always wanted to see the best in people.”

Darian and her boyfriend did not get married. The relationship ended sadly but amicably in 2018. She moved back in with her grandparents and got a job as a waitress at the Glen café, right across from Flo’s bookshop. Most days they’d have lunch. “We were so happy to have her back at home,” Flo remembers, describing it as a time when they were “so close.” But Darian wasn’t telling her everything.

After the breakup, Darian started seeing a man from Brampton who was two years older than she was. His name was Darnell Reid. Reid had a reputation for being tough. But he and Darian were surprised to find they shared a mutual passion: classic cars. Darian went to car shows and helped Paul build a hot rod by hand. She had the brain of a mechanic. Reid was impressed.

Flo and Paul first met Reid when Darian brought him home for Easter dinner in 2018. She introduced him as simply her “friend.” Paul took him on a tour of his garage, asking questions about the hot rod. Darian introduced him to her grandparents proudly as “a car guy.” Afterward, Flo said, Darian explained to her that Darnell had a “poor upbringing.” This wasn’t true, at least not in economic terms. While Reid and his family declined to be interviewed through his lawyer, he grew up in a solidly middle-class, single-parent family. His mother operated her own hair salon and lived with her children in a tidy, four-bedroom detached brick house with a two-car garage in a nice part of Brampton. Reid lived rent-free in the recently renovated basement apartment.

Michelle in 1999 (Courtesy of Michelle Jones)

Michelle claims she and Darian talked and texted more regularly during this period. Michelle didn’t know Reid personally but says she knew of him, vaguely. She describes him as the kind of guy who hung out in bars and nightclubs, flashed his money around, ordered bottle service and surrounded himself with lots of young, pretty girls. “I’d met loads of guys like him,” Michelle says. “But Darian was naive. She was from Georgetown. Darnell was the first guy who showed her Brampton nightlife.”

At first Darnell treated Darian like a princess, Michelle says. “She’d call me up and say, ‘I know he’s bad, Mom, but he’d never do bad things to me. He protects me from all that stuff.’ ” According to Michelle, he bought her designer clothes, $800 track suits and matching trainers, a luxury handbag and matching wallet. They went on romantic road trips together, just the two of them, to spots like Niagara Falls and Algonquin Park. Darnell also introduced her to nightlife, took her out to all the Brampton clubs. “She was his trophy,” Michelle explains. “He liked to show her off to his friends.”

During this time, Michelle says, Darian partied but never spun out of control the way her birth parents had. But she did become increasingly dependent on Reid, whose grip tightened.

In the winter of 2019, Flo recalls Darian started acting strangely around the house. She’d ask permission for simple things like food or whether it was okay to take a bath. Unexplained bruises appeared on her arms and face, which she attributed to her own clumsiness. According to Michelle, Darian also became more materialistic, interested in money and luxury brands. She dyed her light-brown hair platinum blond and began posting selfies on social media dolled up in false eyelashes.

One night, Michelle recalls, Darian texted her a photo she’d taken of Reid’s illegal gun collection, complete with boxes of ammunition, with the caption “OMG!!!!!” followed by a string of bug-eyed emojis. The weapons looked genuine and there were a lot of them. Reading the text made Michelle’s blood run cold. “Most of these guys maybe have one or two guns, but they flash them around unloaded,” she says. “Really, they’re just for show.” She told Darian not to be impressed and cautioned her to be careful. But she did not tell her to end the relationship.

I ask Michelle why she didn’t send the photo to police and she sighs at the question. “Think about it,” she says. “If I went and did that, either I’d lose her completely or he’d hurt her or hurt me, probably both. He was fully capable of it. Why do you think he had those guns in the first place? I wasn’t going to f–k with him. I’m not stupid.”

Even more disturbing than Reid’s guns was how much they seemed to excite Darian. Why was she titillated when clearly she ought to be terrified? Michelle has a theory. “I think in a f–ked-up way she wanted to impress me,” she says. “I also think she was curious. He showed her a world she’d never seen.”

It was in the winter of 2019, Michelle says, that Darian and Reid started fighting—jealous lover’s spats at first. Darian thought he was seeing other girls but he denied it. He’d get angry at the way she looked at other guys. They broke up and got back together several times. He’d get angry, she confided in Michelle, sometimes even rough, but later he’d apologize profusely and threaten to kill himself. Darian always forgave him.

She brought him home to her mother’s house in Listowel that winter. As with Flo and Paul, he didn’t say much. The thing Michelle remembers most vividly is the way he seemed able to control Darian with his eyes. “He had this look. All he had to do was put it on her and she was like a robot. She’d stop what she was doing and walk straight back and sit down next to him.”

***

On a warm July night in 2019, Darian came downstairs in her slippers and dressing gown and told her grandparents she was going out for a smoke. When she hadn’t returned a few minutes later, they looked out the window and saw Darnell Reid’s Mercedes. “We’re just having a chat!” Darian called to them brightly. Then they watched as Reid pulled her into the passenger side of his car and sped away. They called Darian’s phone, which rang where she had left it, on the dresser in her room. They were frantic.

Later that night, Darian walked into the house, still in her dressing gown and slippers. She tried to cover her face, but Flo pulled her hands away and saw she was severely bruised, her lips swollen and bleeding. Darian cried and told them the truth: Darnell had driven her to an old abandoned mill and threatened to shoot her. Then he’d beaten her up in the car. Eventually an anonymous passerby heard her screams and alerted Halton police, who showed up. They questioned Reid and sent Darian home, requesting she come into the station the next day. She’d walked all the way home in the dark, bleeding, in her pyjamas. The next day, at Flo’s urging, Darian went in to talk to the police. She insisted on going alone; she returned a couple hours later and went straight to her room, where she laid in bed for the rest of the day. Reid was charged with assault and later released without bail after agreeing to comply with a court order forbidding him to contact Darian in any way. She promised her grandparents the relationship was over for good.

Flo and Paul told me that after working with victims’ services, they believe Darian wasn’t simply abused by Reid—she was trafficked. Trafficking, according to the Canadian Criminal Code, is defined as the “illegal recruitment, transportation or hiding of someone for the purpose of exploiting them.” While the practice is usually associated with prostitution and/or forced labour, often involving illegal migrants, in fact the majority of trafficking cases involve victims who are groomed and trafficked within their own communities, often while continuing to live in their parents’ homes. Prostitution is often, but not always, a part of it. In Darian’s case, it may have been simply a method of control. Whatever their end goal, all traffickers methodically seek out vulnerable targets, then proceed to break down their confidence through sexual and emotional violence. Over time, this makes their victims dependant—a kind of intimate brainwashing.

Darian might not have seemed vulnerable on the surface but she’d confided in Reid about her past. Perhaps he instinctively sensed Darian’s childhood made her vulnerable. Despite the unwavering stability of her grandparents, Darian was a girl who’d suffered—the early abandonment by her mother and later, the loss of her father. And as Michelle points out, she was also soft-hearted. She forgave Reid like she forgave her mother. Like so many victims, she kept on forgiving until she couldn’t forgive anymore.

Human trafficking rates in Ontario, and Peel region in particular, have risen steadily in recent years, prompting the force to form a separate task force to focus on the issue. Despite this raised awareness, justice for victims is far from assured. From 2014 to 2018, there were 2,120 charges of trafficking laid in the City of Toronto, resulting in just 56 convictions.

Through police victims’ services, Flo and Paul attended counselling for families of abuse and trafficking victims. This support, they say, was invaluable in helping understand the control Reid seemed to exert over their granddaughter. They urged Darian to do the same, gave her all the information pamphlets and lists of numbers to call. She spoke to a counsellor over the phone a few times but she soon gave up on it. Anyway, she assured them, things with Reid were over.

A few weeks after the police incident, Darian was at a car show with her grandparents when she took a call from Reid. She reported it immediately to police, who charged him with breaching the order, then released him the same day on $2,000 bail. According to court documents, he was ordered to live at his mother’s home and banned from having weapons.

Then one night the following October, Flo and Paul received an upsetting call from Darian, who’d been admitted to hospital in Guelph, Ont. When they arrived to pick her up, her face was bruised and she was suffering from a concussion. She confessed she’d been out with Reid and the police had picked him up, searched his car and then charged him with possession of OxyContin, and again with breaching the no-contact order. The bruises and the concussion, she insisted, were the result of her having passed out on the sidewalk while Reid was being questioned. Police confirmed she’d fainted, but Flo and Paul were doubtful all her injuries were by accident. There were bruises all over her body.

In the months that followed, her grandparents say, Darian made a genuine effort to break things off with Reid. She changed her phone number at least a dozen times.

Then, on May 23, Flo and Paul were awoken by yet another panicked call. Darian was sobbing, hysterical, and claimed she’d been in a hit and run. She was only a few streets away at a neighbour’s house. They rushed over and found her in an awful state, bleeding and bruised everywhere. She described a speeding car, how it had come out of nowhere while she was crossing the street in the dark, thrown her several feet then sped off. As Paul and Flo were talking to Darian on their neighbour’s lawn, another car, one they didn’t recognize, drove by slowly. When Paul walked over to see who was inside, it sped off. The windows were tinted, but he managed to get part of the plate number and called it into police. Darnell was picked up later that night, in a rented car that matched the plate number. He was charged, once again, with breaking the protection order, as well as impaired driving and possession of an illegal firearm. He was put in custody without chance of bail pending trial.

When police later told the Henderson-Bellmans that Reid had finally been locked up, Flo says she wept with relief. Darian admitted to her grandparents the hit and run had been a lie. In fact she’d been driving with Reid. He was drunk and high on pills and became agitated, she said. He’d shown her his gun and threatened to shoot her and her grandparents. When she tried to escape, he began beating her with his fist while driving. Darian punched him hard in the face, then opened the passenger-side door and attempted to jump from the moving car. But Reid caught hold of her arm and dragged her beside the moving vehicle until she slipped from his grip. Darian told Flo and Paul she managed to get up and then ran terrorized down the road in the opposite direction. In a rage, Reid reversed hard, knocking Darian flat. Then he drove away, tires squealing, leaving Darian to bleed in the street.

Paul says he can’t stop thinking about the fact that it was Reid who drove up in the rental car that night. The police told Paul he was lucky he hadn’t knocked on the window, because Reid had a gun. But the fact that he didn’t knock, that he backed away and called police instead, is something Paul says he’ll regret for the rest of his life. He breaks down weeping at the memory. “I could have taken a bullet for her,” he says. “I would have been happy to. I could have done that but I didn’t. I have to live with that every day.”

In normal times, this might have been the end of the story, or at least the start of a newer, happier one. Darian’s bruises might have healed, and later her emotional trauma. She might have graduated from high school, found a career, started dating again. But we are not living in normal times. And that is not what happened.

The Henderson-Bellmans’ sense of relief was short-lived. It evaporated less than a week later, when police regretfully informed Darian that Reid had been released yet again on bail due to concerns for his health because of the spread of COVID-19 within the prison population. Once again his mother put up bail, this time in the amount of $25,000. Reid was put on house arrest at his mother’s. When Darian told Flo the news, her grandmother says she seemed unconcerned. “Don’t worry, Nana,” she reportedly said, “nothing bad can happen. He’s wearing one of those ankle bracelets.” Inwardly, Flo shook her head, sceptical that an electronic monitoring device would stop Darnell Reid from posing a threat. (Indeed, police sources later told me they consider these devices “essentially useless” when it comes to preventing impulsive violent criminals from reoffending.)

As the restrictions lifted and the summer progressed, Darian seemed to be moving on. She began doing Grade 12 courses by correspondence. She paid off her bills, worked on her resumé. She even joined a dating app—something she’d sworn she’d never do. One night in late July, she surprised her grandparents by going out on a first date. When the suitor came to pick her up at the house, she insisted he come in first and introduce himself to her Nana and Papa, which he graciously did. Flo remembers him as “a nice, young fellow.” Later, Darian told them the date went well.

Michelle, however, told me Darian had confided in her that she was secretly dating someone else during this time: a friend of Reid’s. If he found out, she was sure he’d kill her.

***

The day after Darian’s online date was July 28, a Tuesday. The morning was clear but hot—31° C with humidity building throughout the day. Paul was building a cupola on the garage roof; Darian and Flo helped, handing him up sections. Next, he added a hotrod weather vane. Darian said she was going to study with a girlfriend nearby, then kissed and hugged both her grandparents goodbye. They watched her walk down the street with her book bag, looking like a schoolgirl on her way to class. Around half past one, Paul texted Darian a proud photo of his handiwork. Darian wrote back minutes later to say she couldn’t wait to see it. “Be home in a bit,” she wrote, signing off with love.

By afternoon it was sweltering. In a celebratory mood, Paul convinced Flo they should take the hot rod out to get ice cream. On the way home from the parlour, they received a strange call. A friend of Darian’s told Flo there was a rumour on Facebook that Dare was dead. Paul said she’d just texted him an hour ago. At first, they assumed it was a hoax. Then another call came in asking if they’d seen Darian. Alarmed, they pulled over and called Darian’s phone repeatedly but it just rang and rang.

At home, the Henderson-Bellmans became agitated. As day slipped into evening, the sky above Georgetown filled with heavy, bruised clouds; the atmosphere seemed to tighten around them but the heat wouldn’t break. Paul and Flo paced the sitting room and called Darian’s friends, but no one knew where she was—including the girl she was meant to be studying with. Flo called the police and explained the strange calls and informed them that Darian was missing. She explained they were her grandparents but also, crucially, her legal guardians. The receptionist on the switchboard promised to look into it and have an officer call them back. No one did. Around five p.m., they turned on CP24, the local rolling news channel. There was a live report of a fatal shooting in Brampton. One person dead, the other critically injured and in hospital. The house in the report was a low-slung, pale-brick home surrounded by police tape. It could have been any house on any street in the endless identikit crescents and cul-de-sacs of Brampton, but Flo and Paul recognized it instantly. It belonged to Darnell Reid’s mother.

Slowly, without speaking, they lowered themselves to the sofa, eyes fixed on the screen. Silently, reaching for each other’s hands, they continued to watch. For the rest of that night, Flo and Paul vacillated between frantic bursts of activity and periods of wordless shock. They called Darian’s phone in desperation, but again and again it went straight to voice mail. They repeatedly contacted police, who refused to give them any information. They called hospitals and, finally, their friends on the police force, but no one could help them. A few close friends saw the news and came over to support them, including one from Halton victim services. Over and over they prayed that if Darian was involved, that she was the one in hospital, fighting for her life.

What they did not know was this: earlier that day, while they were going to get ice cream in the hot rod, Michelle had seen reports of the shooting and immediately called Halton police. They’d told her to come in to the station immediately; they needed to speak to her in person. She knew this was bad news. For the whole frantic, two-hour drive east on the 401, Michelle listened to the local radio news reports, her face bathed in tears. Earlier that day, a 911 call had come in reporting a shooting. A young woman had been shot five times at close range in the basement of a home, another person badly injured. At 2:30 that afternoon, paramedics arrived and pronounced the woman dead on arrival. Darnell Reid had been taken to hospital, where he remained in critical condition. It was early in the investigation, but police told Michelle they believed he’d turned the gun on himself in a botched suicide attempt.

The police asked Michelle if she could help them by identifying the body. Hysterical with grief, Michelle said she didn’t want to go to the coroner’s, so instead showed them several recent photos of Darian on her phone. The police explained they knew what Darian looked like but the photos wouldn’t help. Somehow on her phone she managed to find a photo of her daughter’s tattoo, the one with Conrad’s name and death date. The police took the photo and thanked her.

For hours after that, Michelle sat with police answering questions, telling them what she knew about the relationship between Darian and Darnell Reid. A couple of hours into the interview, police told her that Paul and Flo had been calling the station, desperate for information. Michelle concedes she asked police not to tell them and that they complied because she was Darian’s mother. “I wanted to go and tell them in person,” she explains, imploring me to believe her. “I felt I owed them that, that it was the right thing to do. I didn’t want them to hear it from some cop the way I had.”

In her grief, Michelle told me, another story was taking shape in her mind. One in which she would walk up the porch steps of the white house in Georgetown and, after she had given Flo and Paul the news, the three of them would have a big family hug, then sit for hours comforting each other and mourning the daughter they loved. “It was stupid. I don’t know what I was thinking. But it came from a good place, I swear to God.”

For Flo and Paul, those hours and hours of not knowing were agony. And for Michelle not to have told police about their role as Darian’s legal guardians and her active parents? Unfathomable.

By the time Michelle arrived at the house it was shortly after midnight, nearly 10 hours after Darian had died. As she walked up to the house where Darian grew up, Michelle says her body filled with dread. When Flo came to the door her face was raw and pink from hours of crying. Michelle began to apologize; an anguished scene ensued. Eventually two off-duty police officers who were present intervened, walking Michelle off the property.

Unbeknownst to Michelle, Flo and Paul had already heard the news. A cop had called them up an hour before and explained they’d been unable to call earlier because Darian’s mother had instructed them not to. When Flo realized Michelle was actually there, in the flesh, that she’d had the temerity to show up at their house after keeping them in hellish limbo for all those hours, it was, she says, like “the final kick in the gut” after a long and brutal beating.

Michelle returned to Listowel. In the days afterward, Flo and Paul wrote a letter to Michelle. Michelle responded with a letter of her own, it arrived in Georgetown by post, two days after Paul and Flo sent theirs. In it, she says she explained everything and begs for their forgiveness, not just for her actions of that day, but for everything else. All of these words were written but none were read. Neither of the letters were opened.

Much has been written of the possibilities for prison reform as a result of the pandemic, but it has included little discussion of how this mass release may have contributed to rates of recidivism among those who, like Darnell Reid, started lockdown incarcerated and finished it on house arrest. While recidivism rates aren’t officially tracked in Canada, recent figures from Statistics Canada show that, from February 2020 to April 2020, the Canadian prison population dropped by a sixth—about 6,000 fewer people in jail than two months before. Overall violent crime rates dropped nationally during this time due to the stay-at-home order, with one exception: femicide.

In an interview with Maclean’s, Peel police chief Duraiappah discussed the complicated sequence of events that led to Darian’s death, which he puts down to the court’s decision to release him despite a history of violence and an illegal weapons charge. Forty per cent of homicides in Peel region are, he says, a result of intimate partner violence.

“Our role in this specific case is very clearly defined,” he explains. “We have to respond to crimes and also protect victims. In Darian’s case, she was the victim of domestic partner violence. We responded to it and held Darnell Reid accountable and brought him before the courts. The Crown did an amazing job. He goes in, then he gets released on bail again two weeks later, then she’s dead. At that point the system did not hold up. If you plot out the system of events, you can pinpoint where it failed. Everybody had a responsibility and I own my wheelhouse.”

Brampton mayor Patrick Brown is adamant that the solution is bail reform, especially for those facing weapons charges. “This is such an egregious example of our justice system failing that young lady and failing our community,” he raged to city council in the days after the killing. “The suspect was arrested for having a firearm and they let him back out again just recently. It’s unimaginable and so I want to continue advocating for this bail reform.”

There have been some notable advances since Darian’s death. In February, Peel police launched what it calls an integrated services hub for anti-human trafficking services to support victims and their families. Constable Joy Brown, head of the Human Trafficking Service Providers Committee, says that trafficking is far more common, even endemic, than Canadians believe. “It can happen to anyone,” she says. “Just the fact that you are a female makes you more vulnerable.”

Peel police also announced last month the creation of a unit aimed at better helping victims of intimate partner violence. The unit is located within a family justice centre that offers a number of services through partner agencies, from housing assistance to legal support. The 48 investigators attached to the unit dress in plain clothes in an effort to be less intimidating to those who mistrust police, and are specially trained to support survivors, manage their cases and interview children. Peel police also say the unit will allow them to increase monitoring of high-risk offenders. The creation of the unit was prompted in part by Darian’s death.

***

Darian’s funeral was a small, private affair because of COVID. Paul’s car club did a memorial drive-by of Flo and Paul’s house and raised funds in Darian’s name. They donated the money to a local women’s shelter. They, like Michelle, would like to see a Darian’s Law—one that stiffens bail terms for defendants charged with weapons offences. Either that, or a women’s shelter, named in her honour.

Although Flo and Paul believe the system failed Darian (“Darian would be alive today if this had been handled properly by the judicial system”), they are devoid of anger toward the Peel and Halton police, whom they insist acted impeccably and should bear no blame. But their generosity does not extend to Michelle.

In our last conversation, Michelle told me tearfully she’s begged Flo and Paul for a memento from Darian’s belongings, “a stuffed animal or anything I can give to my sons to remember their sister by.” According to Michelle, this request was ignored; Flo says she never received a request from Michelle. Similarly, my own (admittedly gentle) attempts to broker a truce were quietly rebuffed. As a reporter, it’s not my place to get involved, but I will say this: Darian’s death stole more than just her life. It stole the forgiveness she showed toward her birth mother, a flawed woman who now grieves alone. It stole Darian’s love, which, for a time, connected her fractured family.

Police say it’s unlikely Darnell Reid will be released again. The allegations against Reid have not been proven. According to Michelle, his friends and family in Brampton maintain he is innocent, seeing it as a double shooting. According to police, forensic evidence disputes this claim.

Flo and Paul say they don’t sleep much these days. Paul keeps thinking of the last text Darian sent, which he keeps on his phone and rereads more often than he should. The time stamp was 1:45 p.m. What happened in those 45 minutes between her sending the text and her death, he wonders? Was she scared? Did she suffer? Had the text been written by someone else? These are the kinds of dark thoughts that continue to plague both of them.

“I wake up in bed sometimes,” Paul says. His voice is strangled. Flo starts to interject but he puts up a big bear hand, determined to get the words out. “I wake up and I imagine her laying on the floor. I think maybe she couldn’t get to her phone? Maybe if she had, then I could have—”

He breaks off and places his big bald pirate head in his hands, where it stays for several minutes while Flo reminiscences fondly about Darian. When he lifts his face, it is flushed.

“Sorry about that,” he says. “I don’t know what got into me just there.”

This is an updated version of a story that first appeared in the June 2021 print issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline “Lessons from Darian.”