A grand day for warriors at Donald Trump’s White House

Allen Abel: When not double-tasking on fear and finance—cancelling the North Korea summit while loosening banking rules—there were honours to bestow

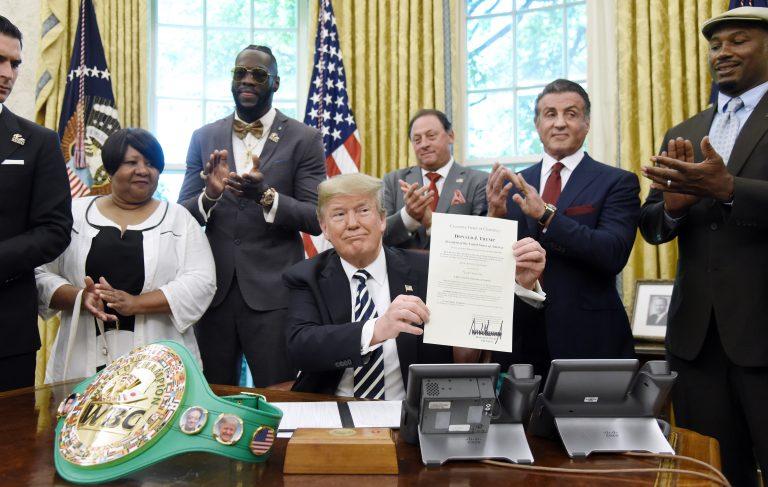

US President Donald Trump holds a signing Executive Grant of Clemency for boxer “Jack Johnson ” in the Oval Office of the White House on May 24, 2018 in Washington, DC. (Olivier Douliery/Getty Images)

Share

A grand day for warriors at Donald Trump’s White House enfolded the granting of posthumous mercy to a long-scorned pugilist by an unpardonably bellicose populist; the awarding of the American nation’s most sacred token of courage in combat by a bone-spurred Commander-In-Chief, and a Dear Jong letter – signed with a flourishing hand and a warm “Sincerely yours” — that nudged a weary world again toward the brink of nuclear doom.

In the interstices, the 45th president found time to sign a law to loosen federal restrictions on the banking system, and to hail the decision by the (white) barons of the National Football League to rigorously uphold their (black) players’ constitutional right to protest racism and violence as long as nobody in the stands or watching on TV can see them do it.

Even by Trumpian standards, the eve of the 2018 Memorial Day weekend will be remembered as a watershed – principally for The Donald’s steely, Nobel-be-damned backbone as he declared his June summit with Kim Jong-un to be a NoKo no-go. This came in the form of a missive that – as White House reporters were told by a senior administration official with the pride of a grade-school pupil’s papa – “The president dictated every word of the letter himself.”

Sadly, I was forced to cancel the Summit Meeting in Singapore with Kim Jong Un. pic.twitter.com/rLwXxBxFKx

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 24, 2018

Behind the abrupt annulation of what always had been the most improbable summit of the century, this official disclosed, was a planned meeting in Singapore last week at which U.S. representatives “waited and they waited, and the North Koreans didn’t show up.”

Leaving American officials at the altar was gauche; the declaration by North Korean state radio that the United States “meet us in a meeting room or encounter us in a nuclear to nuclear showdown” showed a “strange lack of judgment,” and inviting journalists to witness the detonation of a “nuclear test site” in the pariah state’s uplands that may have been nothing more than a decoy hole in the ground was nefarious, the administration declaimed.

But labelling Vice President Mike Pence a “dummy” – as Pyongyang’s media lapdogs did on Wednesday night – THAT seems to have been the final straw.

“If and when Kim Jong-un chooses to engage in constructive dialogue and actions, I am waiting,” Trump stated Thursday morning at the free-the-banks signing ceremony. (Pence stood mutely just behind his ventriloquist’s left shoulder, playing his usual Walter to Trump’s Jeff Dunham, as inanimate as all vice presidents have been since 1789.)

“In the meantime,“ Trump went on, “our very strong sanctions — by far the strongest sanctions ever imposed — and maximum pressure campaign will continue, as it has been continuing. But no matter what happens and what we do, we will never, ever compromise the safety and security of the United States of America.”

For Trump, calling the Communists’ bluff seemed to carry no immediate downside; as he reminded Little Rocket Man in his morning epistle, “You talk about your nuclear capabilities, but ours are so massive and powerful that I pray to God they will never have to be used.” (Despite their previous, astonishing, short-lived bonhomie, Messrs. Trump and Kim never had FaceTimed each other directly, the White House disclosed.) Yet this return to the “my button is bigger than your button” name-calling of last winter barely rattled the stock markets – the NASDAQ exchange closed down a mere one-fiftieth of one per cent.

Across the Pacific, whatever backlash (or backslapping) might await Kim Jong-un from his kow-towing elites and his own rocketeers was beyond exterior knowing. The newspaper Rodong Sinmun, the one-party state’s preferred pulp-fiction outlet, never had mentioned that the third-generation Supreme Leader was intending to meet Donald Trump in the first place. There was no need for the rag to rush out a five-star Extra to break the news that the swains had broken up by text, but imagine how much face the Young Leader will lose should he back off the B.S. and make another date with The Donald.

(Indeed, by nightfall in Washington — another brilliant Red Friday morning in Pyongyang — the northerners seemed to be walking back their backtalk, with the vice foreign minister saying that his rotund little leader remains ready to meet the American president “at any time.”)

On Thursday, Trump’s dismay that “This is a tremendous setback for North Korea and, indeed, a setback for the world,” followed immediately by his assurance that “Nobody should be anxious. We have to get it right” came in the company of several members of Congress who had come to watch him sign the banking bill. But even as the president was double-tasking on fear and finance, a reporter looked out the door of the Roosevelt Room and spotted Sylvester Stallone walking down the hallway.

Stallone, who once had been mooted as Trump’s choice to head the National Endowment for the Arts – a long-time right-wing bugbear – had come to the executive mansion to watch the president pardon the late Jack Johnson, the African-American heavyweight boxing champion of the early 1900s who, not having a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel at his disposal, was convicted of bringing a woman across a state line for “immoral purposes.”

While Johnson’s descendants and supporters had lobbied for his exculpation for decades; although a bill to forgive him had passed the House but not the Senate; although senators as oppositional as John McCain and Harry Reid had appealed personally to Barack Obama for clemency for the scandalized champion, in the end what led to Donald Trump’s pardon of John Arthur Johnson was, in the president’s words, “this was very important to Sylvester Stallone — my friend for a long time.”

Jack Johnson, said Donald Trump, “had a conviction that occurred during a period of tremendous racial tension in the United States,” as if this period ever has concluded. Indeed, on the same morning that he set the ghost of Jack Johnson free, Trump ballyhooed the NFL’s decision to closet its Kaepernicks, telling FOX News that “You have to stand proudly for the national anthem or you shouldn’t be playing, you shouldn’t be there — maybe you shouldn’t be in the country.”

To Donald Trump, the truest American is the soldier that he himself never had the courage to become; the president’s own career in uniform ended when he graduated from a military academy in 1964 and begged off the War in Vietnam because of his supposedly balky feet. But now, in the East Room, beneath the full-length portraits of General George Washington and Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt, the 45th president was hanging the Medal of Honor around the neck of a Navy SEAL named Britt Slabinski who, six months after 9-11, climbed out of a shattered helicopter and up the winter face of an Afghan mountain – in the face of al-Qaeda fire; as his comrades fell dead around him – because one of his brothers-in-arms was bleeding, wounded at the peak.

“They would be outmanned, outgunned, and fighting uphill on a steep, icy mountain,” Trump said. “And every solider knows you don’t want to fight uphill. They learned that at Gettysburg — you don’t fight uphill. But they would face freezing temperatures, and bitter winds, at the highest altitude of battle in the history of the American military. This was the highest point where we ever fought. The odds were not good. They were not in their favour.

“But Britt and his team didn’t even hesitate for a moment. They made their decision. For them it was an easy one. They went back to that mountain.”

The honoree and his family and the families of brave men who fought and died at this and other Gettysburgs got up and walked to a reception in the Grand Foyer, where a band was playing and wine was being poured into crystal glasses under the oil paintings of Bill Clinton and the Bushes. And this was the last the world was supposed to see of Donald Trump on this day.

But later, still on the same afternoon, a few miles north of the White House, a bulldozer was pulverizing an old service station adjacent to the subway tracks. Two years earlier, when the impossible candidacy that would become this inflammatory presidency was at its frothing, fulminating height, someone had painted the words DUMP TRUMP in letters as tall as Jack Johnson, as tall as a guided missile, on the wall overlooking the rails.

Now the summit of the millennium had been cancelled, nuclear confrontation was looming again, and the demolition of the garage and the constitution was ongoing, but only the first word of the graffiti had been knocked down. Left standing alone in the late, summery light, in big white and black letters, was TRUMP, winner and still – in his own mind — champion.