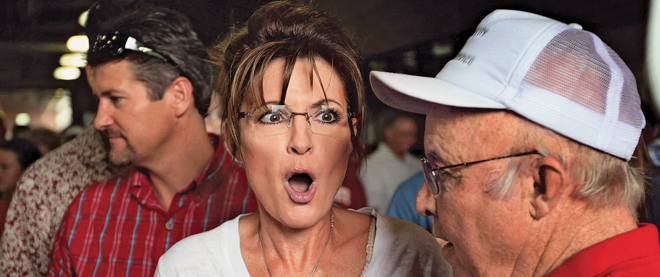

More Palin-tology

A new bio digs up some dirt—but much of the book is about the author himself, says

Scott Olson/Getty Images

Share

Finally, conclusive proof that good fences do not in fact make good neighbours. Even 14-foot high ones, like the monstrosity Sarah Palin’s husband, Todd, and his buddies hastily erected on the edge of the couple’s Wasilla, Alaska, property in the spring of 2010. What the Palins were famously trying to block, of course, were the prying eyes of author Joe McGinniss, who had rented the house next door while researching a book about the Republican party’s foremost shopper. Having a writer best known for his critical take on politics and politicians in such close proximity was a “creepy” infringement on her family’s rights and privacy, the former vice-presidential candidate complained. It was a desperate attempt to gather dirt for a “hit piece,” she said.

McGinniss’s newly published tome, The Rogue: Searching for the Real Sarah Palin, proves that his target’s instincts were correct. But she needn’t have gone to such trouble to obscure the sightlines. However close the author’s view, it wasn’t all that perspicacious.

Sure, there are some titillating bits of gossip, like the tale of Palin snorting lines of coke off the bottom of an overturned oil drum during a snowmobiling expedition, at some unspecified point before she became governor. (An anonymously sourced allegation that first surfaced on a blog in 2007.) Or the revelation that she slept with Glen Rice, a college basketball player who went on to play for the NBA’s Miami Heat, back before she married Todd. (A one-night stand that McGinniss uses to advance the thesis that Palin had a “fetish for black guys,” just four paragraphs after suggesting she transferred from Hawaii Pacific University to a small Idaho college because of her discomfort with “people of colour.”) The self-described “Hockey Mom” is also, apparently, an indifferent parent who hardly ever goes to games, has a loveless marriage, and is a completely hopeless housekeeper. “She couldn’t do grilled cheese. She’d burn water,” quoth someone described as “an old friend.”

But the book is largely a rehash of political misdeeds, sins, and scandals that have been aired out repeatedly since Palin burst onto the U.S. national scene in 2008. She and Todd are vengeful with their enemies, as illustrated by their repeated attempts to get a state trooper who used to be married to Sarah’s sister fired from his job. She’s a kooky evangelical Christian who believes that the Earth was created 6,000 years ago, that humans coexisted with dinosaurs, and the Rapture is imminent. Trig Paxson Van Palin (a nod to her favourite rock band) has never been “proven” to be her baby, and even if he is, she uses the Down’s syndrome child like “a prop.”

Those who love her—Palin’s selective 2009 memoir Going Rogue: An American Life sold more than two million copies—don’t care about this stuff. And the millions who loathe her are already steeped in it.

The most remarkable thing about McGinniss’s Palin biography is how much of it is about him: fond memories of people he met 35 years ago, what he cooked for dinner on his barbeque, how much he loves his wife. “I spend a quiet Fourth of July with the grebes and the birds and my squirrel,” begins chapter 15. His decision to move in next door to his subject made him part of the story, and it appears to have been a lucky break for him. Pages and pages are devoted to what Palin and others said or wrote about Joe McGinniss. And he defends his actions at length, never stinting on testimonials to his good character. One suspects it would have been an awfully thin volume without the high fence and the controversy.

It all has a curious effect. By the end of the 320 pages, even Palin’s fiercest critics might feel a twinge of sympathy for her. And the author himself seems to be as fatigued by the material as his audience. “What should never have been more than a freaky sideshow performed on a carnival midway was transformed by John McCain’s desperation into what many still seem to see as the greatest show on earth,” McGinniss writes, lamenting the media’s—but apparently not his own—codependency. “Actually, it’s long past time to strike the tent.”

If people get the government they deserve, they must also get the candidates they merit. And perhaps it works the same way with authors and their subjects.In the final analysis, The Rogue is overhyped and of little substance. Just like Palin herself.