A continent divided by the pandemic

Ethan Lou: Back where I spent my childhood, the COVID-19 crisis has thrust an uncomfortable truth into the fore, that European solidarity is weakening

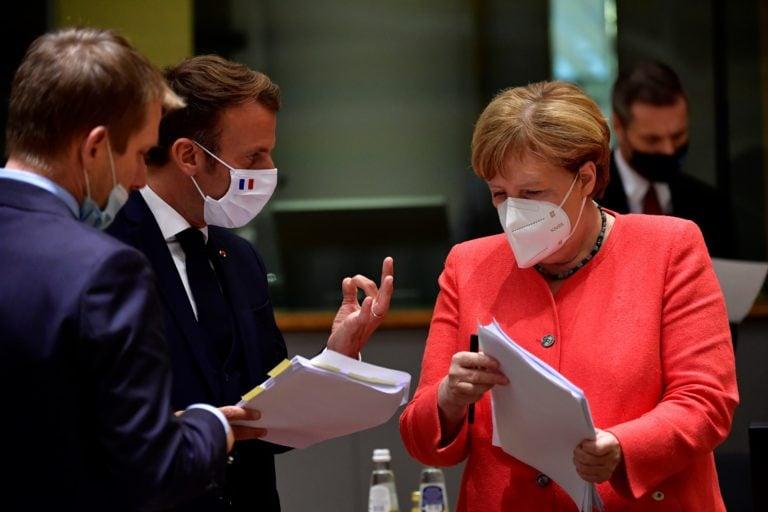

German Chancellor Angela Merkel looks on next to French President Emmanuel Macron during an EU summit in Brussels on July 20, 2020 (JOHN THYS/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Share

Ethan Lou is the author of Field Notes from a Pandemic: A Journey through a World Suspended, to be published fall 2020 by McClelland and Stewart

In February, when I left China, where I was born, I thought I had escaped the worst of it, the lockdown and social isolation brought by COVID-19. Landing afterward in Germany, where I had spent my childhood, was a welcomed relief.

Then amid a surge in infection, the World Health Organization labelled Europe the new epicentre. The lockdown descended rapidly, even down to my little town of 75,000, its claim to fame being the site of the composer Richard Wagner’s opera house.

“The police will be under an obligation to check compliance,” read a “Decree” from the southeastern state of Bavaria. In the husk of downtown Bayreuth, I was reliving what I had just left behind, like some terrible version of Groundhog Day.

Yet it was also different. The pandemic had hit at a rising China, halting and perhaps even reversing new growth, but it had landed on a Europe already battered by its myriad crises and marred in division. Times of uncertainty reveal true mettle. The pandemic has thrust an uncomfortable truth into the fore: European solidarity is weakening, and that has implications beyond the continent.

The infamous Wall Street Journal coronavirus piece “China is the real sick man of Asia,” from back when the virus was still confined to the East, has not aged well. Everything it said about China—about the virus’s blow to its economy and its place in the world—is now effectively a warning for Europe.

As the pandemic began, leaders scarcely mentioned the continent’s common struggle when addressing their countries, not even German Chancellor Angela Merkel, widely seen as the de facto leader of the bloc.

Despite the common market the EU is supposed to have, national leaders hoarded and scrambled for medical supplies. Italy, where infections had outstripped China’s, complained it had been abandoned.

Europe did manage some solidarity eventually, with various forms of aid flowing from the less to the more affected countries. But the trickle of that was slow. The first hints of France and Germany’s trillion-dollar recovery fund came nearly three months after the first lockdown of parts of Italy.

European Union leaders reached agreement on that fund toward the end of July, but the lead-up to it was marred by bitterness and rancor. The well-off and less-devastated countries had been unwilling to share the burdens of the poor and hard-hit.

The American billionaire financier George Soros has said the collapse of the European Union in the wake of the pandemic “is not a theoretical possibility; it may be the tragic reality.”

Consider the unprecedented travel restrictions that had descended on the Schengen no-border zone—a region that had once encapsulated the free movement of people and goods the EU is all about. “European solidarity does not exist,” Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic has told his country. Serbia’s not in the bloc, but its joining the EU has been in the works for more than five years. Continental unity is nothing more than “a fairy tale,” Vucic said.

Yet solidarity is about more than just the continent. The EU is an anchor for the current liberal international order, alliances, institutions and a rules-based system dominated by Western democracies and their values. Keeping faith with it formed the foreign-policy premise for middle powers such as Canada for more than 70 years.

With the current trajectory of the United States, gradually abdicating its traditional world-leadership role, a Europe in disunity could effectively lead to a further weakening of that international order.

The 21st century has already been harsh on the continent—Middle East conflicts and the ensuing refugee crisis, the sovereign-debt economic chaos and rising political polarization, all fuelling and feeding off each other. Growth in the Eurozone has trickled to just over 1 per cent.

All the while, the European Union has fractured, with the United Kingdom already out. The virus exacerbates long-standing divisions.

Challengers have already taken notice. The EU has accused China and Russia—which deny the allegations—of using “targeted influence operations and disinformation” online to “undermine democratic debate,” seeking to ride the bent back of what they hope to be a new sick man.

As well, China has prominently publicized aid sent to Italy, sometimes falsely. When Spain, France and the Czech Republic sought Chinese engagement on the virus, the Asian country capitalized on the public-relations moments as well.

It may be cynical to second-guess what is potentially just goodwill, but the results are indisputable. Amid the chaos, the Asian giant is looking more and more like a global leader, a new sort of anchor for a new order. On the virus, Serbia’s Vucic said, “The only country that can help us is China.”

From Germany’s Merkel to the UN secretary-general, all sorts of world leaders have compared the pandemic to the Second World War—an apt observation; at the health crisis’s heels, geopolitical upheaval looms.

The old war had defined an age, spawning the international order we know now. This crisis may be no different.

That trip to Germany was the longest I’ve been back to the country where I spent ages 1 through 6. Everything—from the head cheese to my unexpectedly improving German and even the so-called “continental-shelf” toilets—had been a source of comfort amid the chaos.

Yet being there, in that moment, at the town that hosts Wagner’s opera house, it’s clear, more so than ever before that unless Europe can truly stand together, we will live in the decline of the West.