I’m 60 and I just graduated

Michael Coren: For the most part I’d read more than most of the younger students, and had certainly seen more, but their level of concentration and willingness to study terrified me

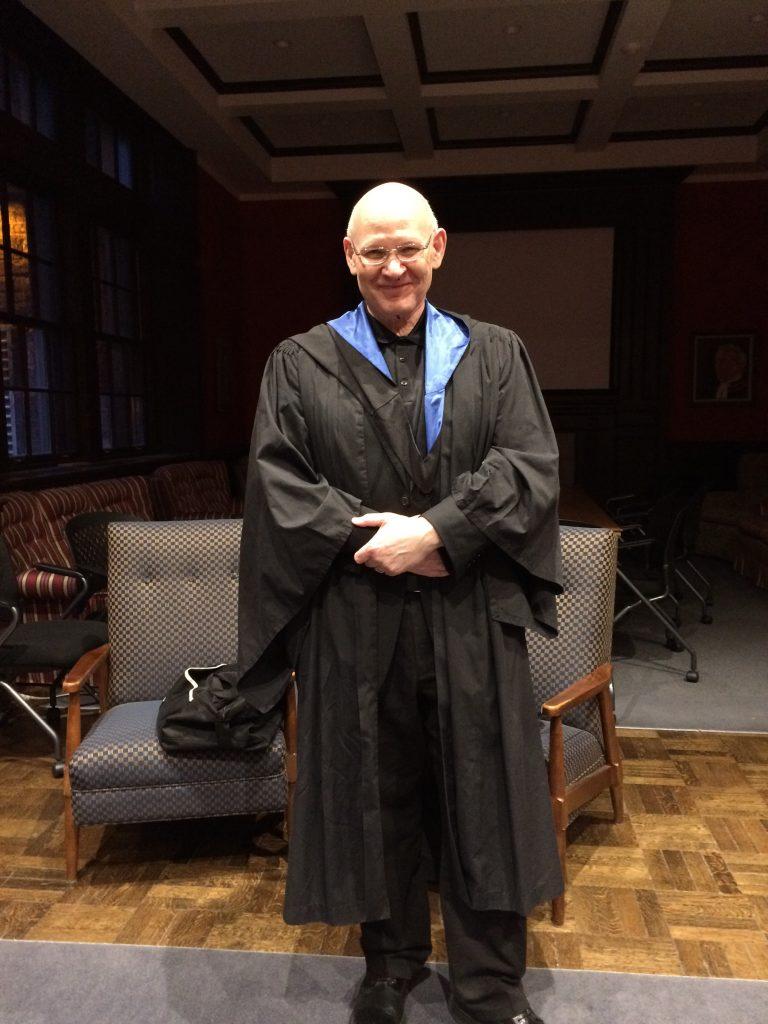

(Courtesy of Michael Coren)

Share

I’m 60 years old and I’ve just graduated from university. Let me be a little more specific. I graduated from a couple of universities in Britain when I was in my early 20s but three years ago decided to start a Masters of Divinity degree at Trinity College, University of Toronto. It came about after a profound change of my personal, spiritual, and thus — by inevitable extension — intellectual life. My life had been transformed and now I wanted to understand at a deeper level what was behind that change, to explore its intellectual underpinnings. On a practical level, our four children were now grown and, as much as they ever are, independent. Financially we were okay. The mortgage was paid, and after losing almost every column, speech, and radio and TV show when I abandoned religious and political conservatism, I’d managed to re-build a career in media that enabled me to speak my mind, and pay the bills, but left enough time to study.

Divinity is the study of theology, usually Christian, and tends to be connected to some sort of church-linked vocation. As an academic subject it’s anchored in antiquity but sails in modern waters — ancient history and the most contemporary political and literary theories mingling and mixing. That was all intriguing and attractive, but it was the banalities of formal study after such a long hiatus that were the most troubling. Old man meets new technology. I’m fairly computer literate but the university’s online demands were bewildering. I remember storming out of my study at home and shouting something about none of it being worth the bloody effort. Our then 18-year-old daughter, more hip-hop than Hegel, shouted from the kitchen, “You said you wanted do it, so do it.” So I did it.

That generational thing is interesting. Undergraduates generally assumed I was a professor until we spoke and I explained, and then they regarded me with either pity or interest. I preferred the latter. I saw students throughout the university — I took courses at four different colleges — at pretty close quarters and genuinely waited, apprehensively, for the extreme identity politics and politically correct intolerance that seems to provoke countless people in conservative media these days. I was disappointed. In the vast majority of cases these kids in their late teens and early 20s were exactly the same as we were forty years ago. If anything they were harder working and more mature, and when they were political it made them more sensitive and empathetic. Of course there were those who had every answer to every problem, as only an 18-year-old sociology student can, but nothing new there, and nothing especially intimidating.

As for the handful of harsh and censorious activists, they have very little influence. And, anyway, the revolution has to breathe, and beneath their sometimes annoying and even unpleasant antics were some authentic grievances and entirely understandable pain. It’s interesting how some older critics become caricatures of “get off my lawn” types but try to disguise it all behind an ostensible regard for the protection of free speech.

The actual class experience is complex for someone of my years. Many of the students were the same age as my kids, and I was older than some of the lecturers. That wasn’t necessarily a problem but it did change relationships. A central point about ageing is that it’s usually noticed more by others than by the person themselves. The triumph of optimism and illusion over reality and knee surgery. Would teaching assistants feel awkward in criticizing my essays? Apparently not. In fact one of the aspects of my time that most surprised me, but shouldn’t have, was the professionalism of most people involved. If I’m honest I think that sub-consciously I’d expected special treatment, more lenient treatment and was even a little pissed when I didn’t receive it.

There is a gang of threats to getting old: nostalgia, complacency, fear, and regret. We see some of this in political attitudes towards immigration and change — the country isn’t like it used to be, my comfort zone has been pierced. Parenting doesn’t help much because the relationship is by its nature hierarchical; being peers with students who have a radically different life experience is a departure because you’re dragged whether you like it or not into new perceptions and understandings. The world is not so novel, certainly not so startling, when you’re in it rather than looking at it.

This is where I say that I learned a great deal from the kids around me, and we all cringe. Problem is, I did. For most of my adult life I knew I’d find work, a home, a good future. Not so for many of my classmates, unless they were from wealthy families. They assumed years of minimum wage jobs, crippling student debts, and trying to find work in industries that were often moribund. I’m not sure I could have coped with that relentless uncertainty. This all helped me to understand my own children more completely, to grasp their willingness to live and work abroad for a few years, and to allow life to unwrap without planning. I’d sometimes put that down to adventurism, and could hear the loving but insistent advice of my father that we always have to look ahead. I suppose we do, but life seems to be much more enjoyable when we do so just a little less frequently.

Academically I always felt relatively secure, even smug. For the most part I’d read more than most of the younger students, and had certainly seen more, but their level of concentration and willingness to study usually terrified me. I got by on being able to write a half-decent essay, and knowing how to read selectively. Age also reminds you that it’s often too late for perfectionism, and I’d sometimes watch as younger students struggled with doubts about whether they could take one more run at an essay, even though what they’d written was more than adequate. It’s not that maturity breeds mediocrity but that contentment and satisfaction should – if we’re fortunate – be one of the benefits of having been around for a while.

Education is a continuum, wherever it takes place. I’ve been formed by 32 years of marriage and the raising of four children just as much as I have by my learning ancient languages, or studying moral theology or religious philosophy. The mind is more than the intellect, and educational growth is achieved through human contact and experience as well as reading books and tackling complex literary and ethical problems. There were times when I considered dropping out of my M.Div., when it all seemed too much, and I was unsure if it was worth all of the work and time. That, I now realize, was insularity and self-doubt creeping in rather than a reaction to the realistic demands of what I was doing. That became so apparent as I sat in the grand hall of Trinity College waiting to receive my diploma. I saw my 25-year-old son sitting with my wife. I knew he was proud, I knew he loved me, but there was something else. He was pleased for me. Pleased that I’d not left it too late, not found reasons to say no. “Not a bad night for the big guy,” he said to me later. No, not bad at all.