What one wedding photo tells us about Mexico’s political paradigm shift

Opinion: By electing AMLO, Mexican voters rejected entrenched elites—and the response to a tone-deaf magazine spread shows both the ire and the work still to be done

Share

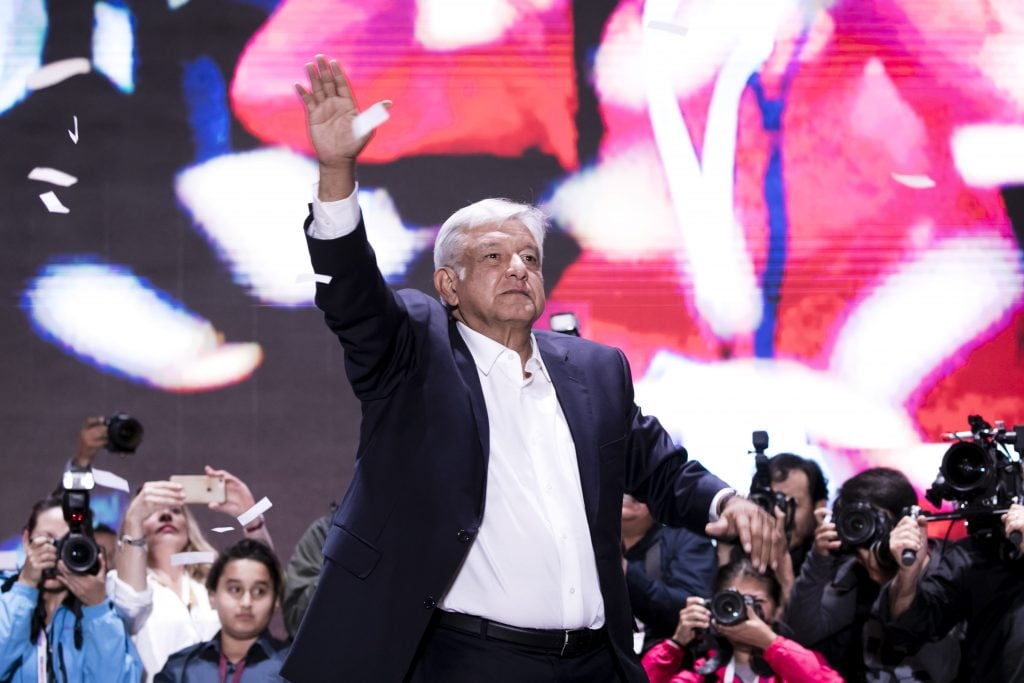

On July 1, Mexico voted for massive change. And Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a silver-haired, 64-year-old from southern Tabasco state, won a staggering 53 per cent of the vote – the most support for a presidential candidate since 1982, when Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) rule went unchallenged.

López Obrador, commonly called AMLO, capitalized on fatigue and frustration with crime, corruption and an underperforming economy, with many Mexicans seeing their social mobility stalled and a job market in which connections matter more than talent.

But shortly after his opponents conceded the election, López Obrador took to the stage with a speech aimed at calming markets that might be spooked by his proximity to power and by 12 years of opponents trying to tie him to the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez. He pledged central bank autonomy, fiscal discipline and the honouring of commitments made with foreign and domestic companies, to name just three.

Amid the promises—all part of an ongoing attempt to moderate his image—the left-leaning populist and three-time presidential candidate returned to an old refrain: “For the good of all; the poor first.” It was the promise on which he ran on in 2006 and lost narrowly, before switching in 2018 for an anti-corruption discourse. It is, however, still the core of AMLO’s appeal.

“We will listen to all, attend to all, respect all,” López Obrador said in central Mexico City. “But we will give preference to the most humble and forgotten, especially the Indigenous peoples of Mexico.”

And yet it took a blithe magazine spread just days later, in one of Mexico’s notoriously snobby society pages, to expose exactly the kind of ignorance that he railed against and that led voters to hand him a dramatic victory—and the possible resistance to come from an elite used to getting its way, and accustomed to showing a crushing indifference to the poor and popular classes.

A wedding portrait published in the society supplement Club—part of the Reforma newspaper—captured a just-married couple who’d met at a Formula 1 race, posing on a sidewalk in the colonial town of San Miguel de Allende. It was previously the haunt of gringos stretching social security cheques, but is increasingly a chi-chi weekend destination. Also appearing in the photo, in the background: an Indigenous woman seated on the sidewalk and selling rag dolls.

The portrait caused a social-media stir, with some Mexicans pointing out how the poor are often seen by wealthier sections of society as little more than part of the scenery, if they’re seen at all. It also reminded many voters of why they opted for AMLO, an austere figure who promises to combat corruption, slash government salaries and strip ex-presidents of their pensions.

“The elections repudiated this Mexico, the Mexico that has seen poverty as part of its folklore,” said Emiliano Ruiz Parra, an author who has covered López Obrador closely.

Mexico’s society supplements mostly showcase the tacky tastes of the nuevo riche and their spoiled offspring—known as mirreyes—whose excesses, sense of entitlement, and need to show off have caused scandals. Such publications shamelessly discriminate, too: just two per cent of the people who have appeared in the December 2016 edition of Quién, a prominent society glossy, had dark skin—even though more than 60 per cent of the population identifies as such, according to an analysis by Buzzfeed Mexico.

Few observers expect the society pages to suddenly become more inclusive or the elites to abandon their insensitivities with AMLO in office. “But we won’t see these mirreyes in high government positions any longer,” Ruiz Parra said.

The mirrey culture of excess, ineptitude and failing upward came to characterize the administration of outgoing PRI president Enrique Peña Nieto—whose wife was revealed to have purchased a $7.2 million mansion from a crony contractor. That entrenched culture in the system was perhaps best summed up by Luis Videgaray, who had the ill-fated idea of inviting then-candidate Donald Trump to Mexico City in the middle of his campaign—and was rewarded with a promotion to foreign minister after that. “I’ve come to learn to learn from you,” he told staff when he was given the foreign ministry portfolio—an attempt at humility that voters interpreted as an admission of lacking the qualifications.

But it also shows how far the new president has to go, as classism has already emerged in the criticism of some of the candidates who have been unexpectedly swept into office with AMLO’s victory. Pedro Carrizales, a former gang member known as “El Mijis,” won a seat in the San Luis Potosí state legislature. But he attracted scandalous attention for his past and for having tattoos—even though he had founded an organization to work with at-risk youth and was about to enter a legislature where lawmakers were found to have siphoned money from anti-poverty programs into shell companies.

“If you are white and have money, you only need to put on a shirt and tie to look like a serious, educated and honest politician,” tweeted Laura García, an NGO director. “If you have tattoos, are brown (or) indigenous woman … you have to fight your way to legitimacy.”

Business and political elites who clashed with AMLO over the past 12 years were quick to congratulate the president-elect—perhaps fearing that old backchannels won’t be as beneficial as before. López Obrador can also claim a clear mandate and could be the most powerful president in decades, with his MORENA party and its allies claiming majorities in both houses of Congress.

“The relationship with the powers-that-be will be different,” said Arturo Franco, an adjunct professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey. “When did you ever see the billionaires of Mexico having to send a video ‘love letter’ to the elected president?”

For his part, López Obrador has called elites “fifis,” or snobs, and disparaged his opponents as “the mafia in power.” He speaks painfully slowly with a regional costeño accent, which would make it easy for his opponents to brand him a provincial hick, but allowed him to appeal to the poor. And on his tireless tours of the country, AMLO coined folksy lines appealing to the popular classes, including “don’t trade dignity for a handout of frijol con gorgojo,” or rotten beans, a reference to the rampant vote-buying in poor areas prior to elections.

But his appeals to class were much more subtle in 2018. Instead of appearing in pictures at posh restaurants—a common practice among much of Mexico’s political class—he won over fans and foodies for his tweets of eating breakfasts of barbacoa (and finding the best spots in the country.)

Mostly, though, he railed against a miserable status quo of crime, corruption and poverty. He benefitted from being out of government since leaving the Mexico City mayor’s office in 2005, too, as the decade-long drug war has claimed more than 200,000 lives and corruption consumed President Enrique Peña Nieto’s outgoing PRI government. Such was the appetite for change that even a candidate like AMLO—who was sunk in 2006 by attack ads calling him “a danger for Mexico,” a tag that resonated with a conservative electorate—was supported by 65 per cent of Mexicans with university degrees, according to an exit poll by Parametría.

“If some voters did lose their fear of AMLO and voted for him in 2018, it is because the last 12 years have been terrifying. There is something Mexicans can fear more than a leftist government: the death and disappearance of thousands of Mexicans,” said Regina Larrea, a Mexican national studying at Harvard Law School. “I voted for AMLO because I want change. My vote was a vote of hope. I want a more fair, more equal, and less dangerous country.”

Ironically, exit polls showed the poor and least educated (often solid PRI supporters, who are coerced by clientelistic organizations) supporting AMLO less than the middle and upper classes.

“The poor lady sitting there [in the wedding portrait] was not an AMLO supporter,” Franco said. “It’s more likely that one of the (couple) getting married was—and more likely the photographer.”