Who is to blame when Canada’s social services upend families?

Opinion: The machinery of our children’s aid systems are doing harm, writes Andray Domise—but the machinery is built and operated by people

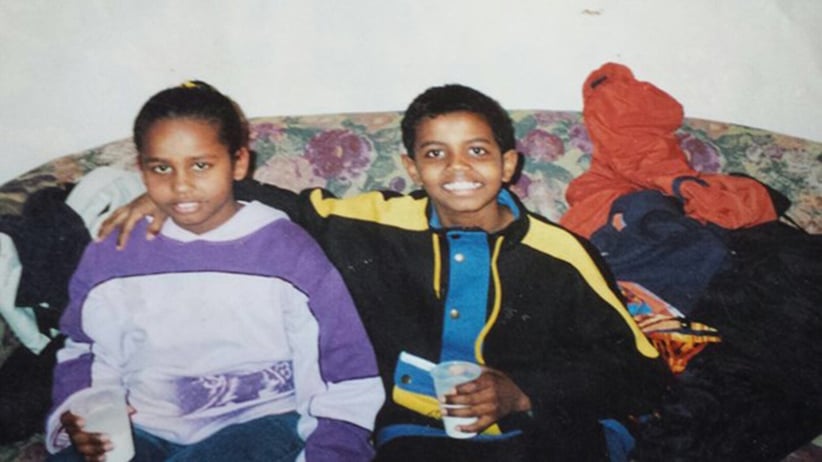

Right, Abdoul Abdi.

Share

A couple of decades ago, a close relative of mine switched careers away from Ontario’s social services sector. She’d worked in the field for years, in group homes and schools for children with special needs. I had the impression she enjoyed working with young people and effecting a positive impact on their lives, so it came as a surprise that she would leave the field. “It’s not the kids,” she explained at the time. The difficulty in working with a system whose clients included runaways, foster children, and children with special needs, she said, was that the system was set up to continuously fail those children. When failures were discovered, they persisted beyond efforts to improve that system.

The stories of Abdoul Abdi and Tamara Malcolm, though wildly divergent in their origins, are of a piece with the kinds of failures that have plagued children’s aid services across the country, and which illustrate the ways bureaucratic racism can upend lives and destroy families. I don’t believe that people who work in the sector are to blame for its failures. But there is a singular frustration that many share—both in the social services area and in the communities where youth are most often taken into care—that systems designed to protect can so often do grievous harm. The cases of Abdi and Malcolm have only worsened these frustrations.

READ MORE: How Canada’s child-welfare system fails refugees like Abdi

Shortly after Abdi and his family came to Canada as refugees from Somalia, he was removed by police and placed into the care of Nova Scotia Department of Community Services. To this day, Abdi’s family claims they weren’t informed why he and his sister Fatuma were removed; both Abdoul and Fatuma have said they were neither abused nor neglected. For years, Abdi’s family fought to regain custody, while he was bounced from one foster home to the next. During this time, Abdi’s family obtained citizenship. But the Department of Community Services failed to make an application on his own behalf—a failure he discovered only after he was convicted on assault charges.

Tamara Malcolm, on the other hand, is an Indigenous woman whose involvement with the system came not from any criminal action on her part, but due to an a violent ex-partner who was found to be abusing her son. In a Kafkaesque twist that’s become a signature for Canadian social services agencies where Indigenous communities are involved, Malcolm’s children were taken from her based on the abuse that someone else committed, and kept from her by West Region Child and Family Services even after stabilizing her household environment.

For ten years, despite no contact with her ex-partner (she has since married, moved to Ontario with her husband, and given birth to a daughter), Malcolm’s children have been kept from returning home. As detailed in the story she gave to Maclean’s reporter Kyle Edwards, as well as her numerous Twitter updates, Malcolm has not only been threatened by the agency for trying to raise awareness of her situation, she’s been forced to spend her own money to combat a system that, where breaking up Indigenous families is concerned, has seemingly limitless reserves of cash to spend.

READ MORE: Inside the crisis around First Nations kids in foster care

Despite the compounding loop of errors and oversights that put Abdi’s family through hell, the RCMP continues to pursue the agenda of deporting him to a country whose civil war his family fled when he was six years old. The RCMP does this because the province of Nova Scotia failed him, and no one seems to be willing or able to take accountability for that fact. Despite the decade that Tamara Malcolm has spent trying to prove her fitness as a mother, and despite her oldest son attempting suicide while in foster care, West Region Child and Family Services continues to fracture her family.

It’s not just the community voicing these frustrations. Provincial and federal ministers, as well as the Prime Minister himselfagree that the machinery of our children’s aid systems can, and often do cause irreparable harm. But the thing is, the machinery is built and operated by people. Within the framework of our system, even despite recent updates in Ontario and Nova Scotia, for example, communities are still being affected by outdated regulations often steeped in bureaucratic discrimination and cultural misunderstandings. Those communities are being acted upon by people following orders.

Malcolm’s children weren’t ripped from her arms by a system. Machinery didn’t place a condition on her son’s Christmas visit asking her to stop tweeting about trying to reunify her family; people did that. The system didn’t take Abdi from his family as a child, neglect to file necessary paperwork, and ultimately place him in far greater jeopardy than if he’d been left in their care. People who collect a biweekly paycheque did this, and are still doing this to him. Aside from government intervention to stop these injustices, there doesn’t appear to be any outcome that doesn’t end in Abdi being deported, and Malcolm’s two children being kept from home until they too age out of the system.

For every Tamara Malcolm and Abdoul Abdi, there are dozens of families who have long since lost the time, the energy, and the money to keep fighting. Meanwhile, Black and Indigenous youth taken into care prior to recent changes, if any, continue to be overrepresented in the foster home and in the detention centre. Indigenous women give birth to children in secret, away from the purported safety of hospitals, to avoid those children being taken away. Touting efforts to do better accomplishes little for families that have already fallen through the system’s built-in holes.

The vast majority of people who work in social services are surely good-hearted, well-intentioned people; it is hard, often thankless work. But it is baffling that the decision-makers among them can collectively allow these failures to happen, repeatedly, and not be shamed enough to resign. At some point accountability should be demanded, but in the meantime a more direct hand is needed to make sure the machinery operates the right way. Ending the injustices being done to Abdoul Abdi and Tamara Malcolm would be a good place to start.