Bob Rae’s rise and fall as Ontario’s first NDP premier, as told through Maclean’s archives

It’s been nearly 25 years since Bob Rae left office, yet his controversial tenure continues to loom over this year’s election campaign

CANADA – SEPTEMBER 06: Bob Rae 1990 (Photo by Boris Spremo/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Share

It may have been NDP leader Andrea Horwath who stood next to PC leader Doug Ford in the last Ontario election debate, but it was former NDP leader Bob Rae who Ford seemed to be campaigning against. He repeatedly warned of massive job losses under the NDP by harking back to the mass layoffs Ontario saw in the early 1990s, when Rae was premier, and he falsely accused Rae’s NDP of pushing Ontario into recession. (The 1990 recession actually began seven months before Rae was elected.)

READ MORE: Bob Rae responds: ‘At some point, the lies have to be answered’

Ford’s attacks weren’t new however. Rae’s controversial tenure as premier from 1990 to 1995 has followed Horwath from well before the campaign even began. But while Horwath has tried to shake off the Rae ghost—“This is not 1990 and I’m certainly not Bob Rae,” she said during the debate.”In fact he’s a Liberal now, but that’s another story”—the reality is a large swath of the Ontario electorate was not even born when Rae was in office.

To help make sense of why Rae continues to cast such a long shadow over this campaign, we delved into the Maclean’s archive and gathered five stories that explain the rise and fall of Bob Rae’s NDP government.

A rejuvenated Bob Rae fires up the NDP (Aug. 27, 1990)

Excerpt:

Rae’s character had been sorely tested in the period leading up to the campaign. Since his wife Arlene’s parents died in a car crash in 1985, three other people close to him have also died unexpectedly. The most shattering of Rae’s losses was the death in June, 1989, of his younger brother David, who lost a battle with cancer at age 32 after Rae underwent a painful bone-marrow transplant in an attempt to save his brother’s life. “It’s not easy to let the public in on your feelings,” Rae told Maclean’s. “But I was devastated by my brother’s illness and death.” In the wake of that loss, Rae decided after considerable soul searching not to seek the leadership of the federal NDP. And Rae’s performance during much of the winter session of the provincial legislature seemed distracted. But, by last spring, the NDP leader confided, “I decided the best tribute to my brother was to pull up my socks.” In fact, Rae now says that the tragedy “allowed me to put a lot of other things in perspective. Minor glitches in a campaign seem just that: minor.”

That new serenity has plainly encouraged confidence in his party, which held 19 of the 130 seats in the previous legislature and in the 1970s captured as many as 38 seats in a smaller, 125-member assembly. Campaign director and key Rae adviser David Agnew, for one, predicted that the party will gain seats across the whole province, not just in traditional NDP urban strongholds. Said Agnew: “The political universe is changing.”

And as the race passed its midpoint last week, the NDP’s campaign remained comparatively glitch-free. Rae’s well-appointed campaign bus ran on time, with the leader concentrating his message on one issue each day. Illustrating an attack on inadequate Liberal spending for education, Rae posed in a school yard dotted with portable classrooms. A decaying apartment building framed his criticism of provincial rent-review legislation. Said Rae: “Our strength is that we run on substantive issues and we put the Liberal record on trial.” (Continue reading.)

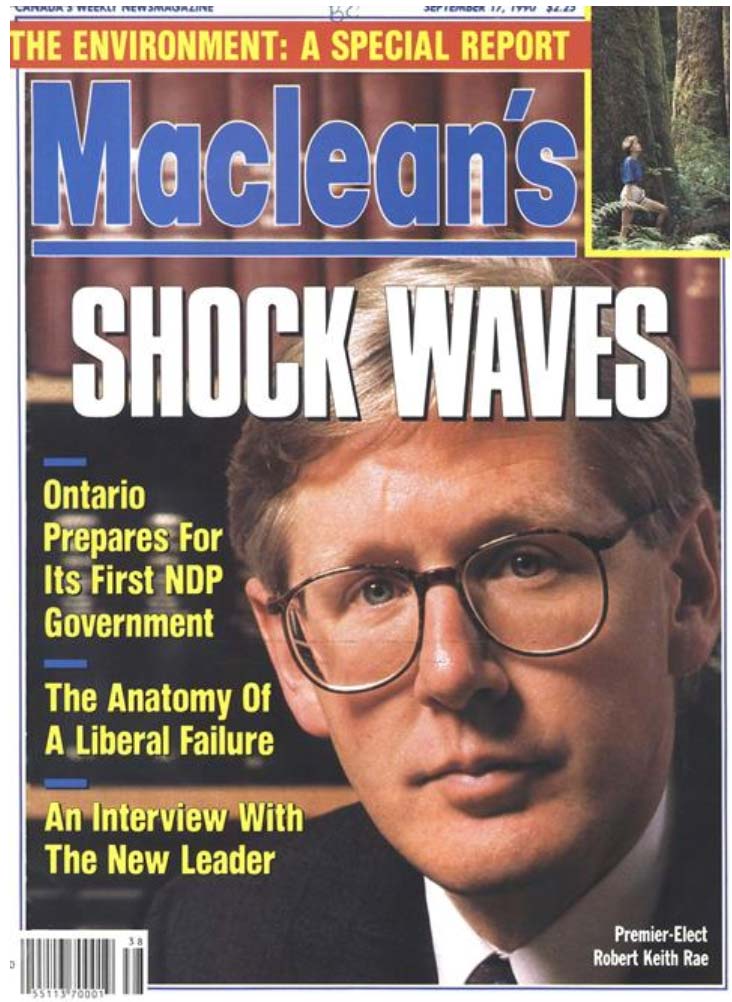

Shock waves as Ontario elects its first NDP socialist government (Sept. 19, 1990)

Excerpt:

Throughout [the campaign’s] 37 days, Rae tirelessly attacked “the Peterson government.” Early in the campaign, he bluntly accused Peterson of “lying.” Later, he portrayed the Liberal premier as the pawn of big business. Among his favorite targets was the Liberal record on the environment. Returning to the issue last week, he scheduled a helicopter flight over the Hamilton-area community of Hagersville, where a 17-day fire at a tire dump last February forced hundreds of residents from their homes— providing dramatic TV pictures. Noting that the Liberals had instituted a $5 tax on new tires last year and had promised that the money would be used for tire disposal, Rae charged, “They used the environment as an excuse to raise the tax—and then they did not invest the money to deal with the problem.”

At the same time, Rae avoided making clear commitments of his own. Said his campaign director, David Agnew: “We were determined not to fall into the trap of making a promise a day.” But Rae did make some pledges. They included a far-reaching economic agenda that would cost $4.2 billion, to be financed at least in part by a minimum eight-per-cent tax on business profits—and from a $1-billion provincial deficit for the next two years. Among Rae’s other economic promises: to limit rent increases to the rate of inflation, and to tax individual incomes earned from real estate speculation and inheritances of more than $1 million.

Those plans generated apprehension among many business leaders. But throughout the campaign, the enthusiastic welcome that voters gave to Rae suggested that he was striking a responsive chord. As the leaders crisscrossed the province, bystanders frequently greeted Rae’s tour buses with thumbs-up signs. In stark contrast, Peterson’s buses frequently attracted considerably ruder gestures. (Continue reading.)

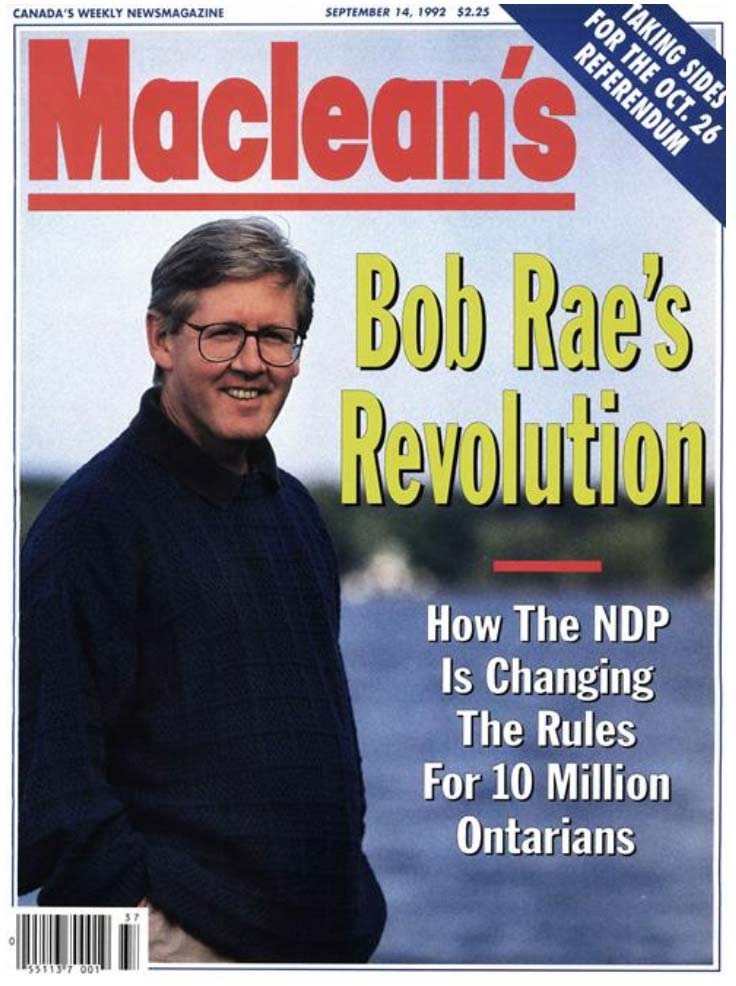

Bob Rae’s revolution (Sept. 14, 1992)

Excerpt:

The NDP’s raft of suggested new laws and programs would have far-reaching effects on everything from picket lines to police stations, classrooms to nursing homes, factories to doctors’ offices. In spite of the diversity of those initiatives, a common thread runs through each of the major elements in the NDP’S social reform agenda. Two years after the party’s surprise election victory over David Peterson’s Liberals on Sept. 6, 1990, its declared aim is nothing less than to change the distribution of power and redress what the government perceives as deep-seated social injustices in Canada’s most populous province. “We are empowering people by creating a new set of rights and new centres of power,” Rae told Maclean’s last week during a break in a three-day cabinet meeting at a lakeside resort north of Toronto. He added that his government’s objective is to generate “countervailing power that will have an impact where power is very much held by small groups.”

Rae’s administration has ventured onto ground where no other North American government has trod—including Canada’s two other NDP provincial governments, in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. One of the most controversial planks in the Ontario NDP platform is what officials describe as the continent’s most progressive labor legislation— a bill that, among other things, would prohibit companies from hiring replacement workers during a strike. It would also ban any union member who wanted to work from going to his job during a strike. And the New Democrats are intent on expanding the pay equity program introduced by the Liberals, already one of the western hemisphere’s most comprehensive efforts to ensure that women are paid as much as men for work of equal value.

Most recently, and perhaps most significantly, Ontario has become the first province in Canada to propose a mandatory employment equity program that would have the effect of requiring privately owned companies to hire and promote women, nonwhites, aboriginals and disabled people.

So far, the government’s opponents have taken aim most directly at the proposed labor laws. Business groups and many of the country’s largest employers have argued that the legislation will give trade unions too much power and frighten off investors from Canada’s industrial heartland. Critics also charge that the New Democrats’ approach to empowering vulnerable or disadvantaged members of society—including workers, visible minorities, women, natives, children, the elderly and the disabled—is fundamentally misguided. They claim that some of the programs will hand power to narrowly focused interest groups rather than to needy individuals. Acknowledged one veteran NDP organizer: “We are getting into some very dicey areas. If we are not careful we can create all kinds of tension.” (Continue reading.)

Ontario unions break with the NDP (Dec. 6, 1993)

As a veteran of demonstrations against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, it was the kind of guerrilla tactic that Ontario NDP Premier Bob Rae might once have appreciated. At the end of an otherwise peaceful protest outside the Ontario legislature last week, angry members of the Ontario Federation of Labor (OFL) broke through a police barricade and began hammering on the oak-panelled doors of the building. ‘We want Rae!” they shouted, as a swirling battery of TV cameras recorded the event. We want Rae!”

…

Two days earlier, delegates to the annual convention of the OFL, which represents about 800,000 workers, had voted to cut all ties with the provincial NDP unless it rescinds Bill 48, its so-called social contract legislation.

That bill, passed in August, outraged labor leaders by freezing wages, forcing workers to take unpaid leave and otherwise breaching existing contracts. The OFL’s motion of censure was far from unanimous: about a third of the 1,500 delegates, most of them from private-sector unions, boycotted the vote, arguing that, for all its faults, the NDP remains labor’s logical political home. Still, the fact that so many of the people who helped to put Rae into power three years ago are now prepared to help bring him down bodes ill for the beleaguered premier. Observes Brian Tanguay, a political scientist at Waterloo’s Wilfrid Laurier University: “This really cripples the NDP at a time when it can least afford it.” (Continue reading.)

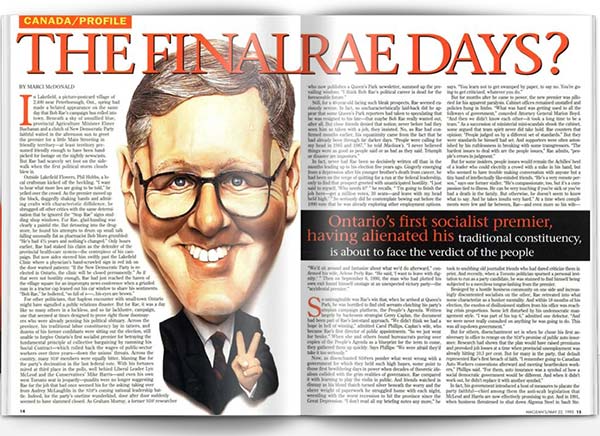

The final Rae days (May 22, 1995)

Excerpt:

Across the province, his traditional labor constituency lay in tatters, and dozens of his former confidants were sitting out the election, still unable to forgive Ontario’s first socialist premier for betraying the fundamental principle of collective bargaining by ramming his Social Contract—which rolled back the wages of public-sector workers over three years—down the unions’ throats. Across the country, many NDP members were equally bitter, blaming Rae for the party’s decimation in the last federal vote. With his fortunes mired at third place in the polls, well behind Liberal Leader Lyn McLeod and the Conservatives’ Mike Harris—and even his own west Toronto seat in jeopardy—pundits were no longer suggesting Rae for the job that had once seemed his for the asking: taking over from Audrey McLaughlin in the NDP’s coming national leadership battle. Indeed, for the party’s onetime Wunderkind, door after door suddenly seemed to have slammed closed. As Graham Murray, a former NDP researcher who now publishes a Queen’s Park newsletter, summed up the prevailing wisdom: “I think Bob Rae’s political career is dead for the foreseeable future.”

…

Now, as disenchanted NDPers ponder what went wrong with a government for which they held such high hopes, some point to those first bewildering days in power when decades of theoretic idealism collided with the grim realities of governance. Rae compared it with learning to play the violin in public. And friends watched in dismay as his blond thatch turned silver beneath the worry and the sheer weight of paperwork he struggled home with each night, wrestling with the worst recession to hit the province since the Great Depression. “I don’t read all my briefing notes any more,” he says. “You learn not to get swamped by paper, to say no. You’re going to get criticized, whatever you do.”

…

Besieged by a hostile business community on one side and increasingly discontented socialists on the other, Rae retreated into what some characterize as a bunker mentality. And within 18 months of his election, the exodus of disillusioned staffers from his office was reaching crisis proportions. Some left disturbed by his undemocratic management style. “I was part of his top 6,” admitted one defector. “And we were never really consulted on anything he was going to do. This was all top-down government.”

…

No matter how deep corporate Canada’s disdain, Rae seemed determined to show that he could play on its terrain and even adopt its lingo. Increasingly, he talked of cuts to social services, welfare fraud and the need for tough choices. Then, word went out among NDP ranks: the premier was so enamored of a W5 television show on how New Zealand dealt with its fiscal crisis that he had ordered copies to screen for his cabinet. The Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) contacted New Zealand union leaders who disputed W5’s version of events, charging that it had been skewed in favor of neoconservative economics. But Rae’s enthusiasm remained unshaken. (Continue reading.)

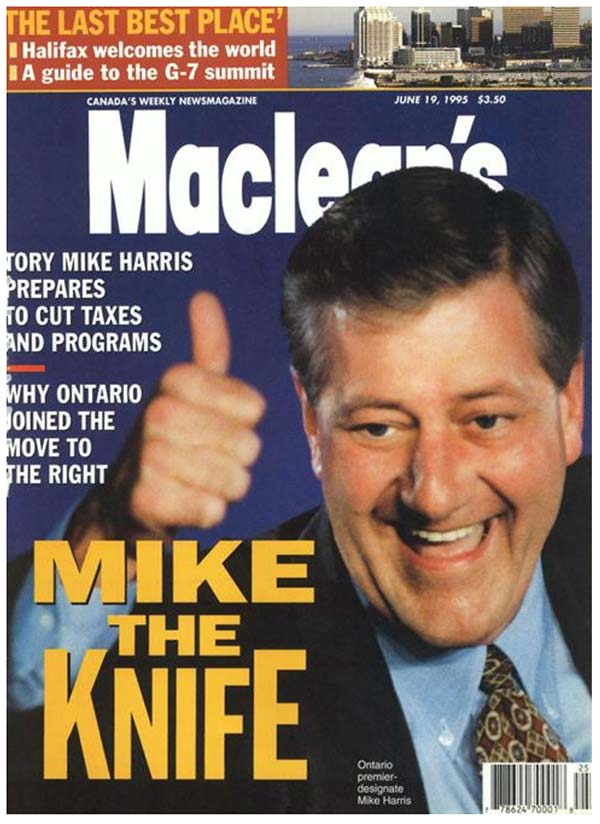

Cover from June 19, 1995: “Mike the knife”

MORE ABOUT 2018 ONTARIO ELECTION:

- The two ex-political staffers behind the Ontario election’s most digital-savvy outside groups

- Why anti-elitism is such a potent force in the Ontario election

- In the Ontario election, there’s a lot of change that’s hard to believe in

- Ontario election 2018: Doug Ford, Andrea Horwath and Kathleen Wynne face off