At the global security gathering in Halifax: Up the down escalator

Paul Wells: Top defence officials gathered at the annual Halifax Security Forum to discuss the big threats. This year’s preoccupation: A re-election of Donald Trump.

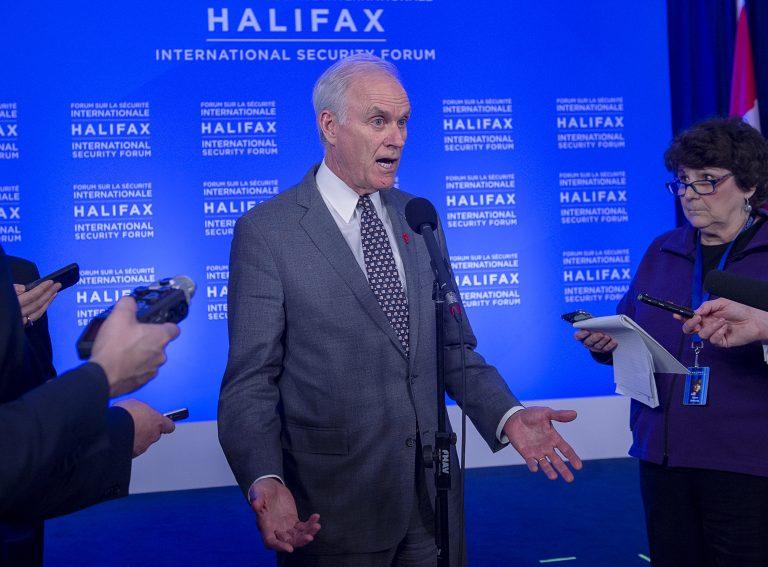

Richard Spencer, U.S. Secretary of the Navy, fields questions at the Halifax International Security Forum on Nov. 23, 2019 (Andrew Vaughan/CP)

Share

You get used to feeling existential dread at the Halifax International Security Forum, which after all exists to give an international who’s who of soldiers, defence and foreign ministers, academics and think tankers a spot to ponder the world’s gravest dangers.

This year’s edition, the 11th since the annual meeting kicked off in 2009, heard the usual fun notes from all over. Cindy McCain presented the conference’s John McCain Prize for Leadership in Public Service to the people of Hong Kong, who were too busy to accept in person. The regime in Iran has lately denied internet access to most of the population. Support for nationalist parties in Germany in 2017 elections closely matched support for Hitler 84 years earlier. The climate is warming, populations are migrating, the “rules-based international order” to which Canada’s government so regularly pledges allegiance is honoured most often in the breach, not to say the travesty.

But the thought I heard most often over coffee or lobster rolls at the Westin Nova Scotian, during breaks from the official program, was this: What if Donald Trump wins next year’s U.S. presidential election?

By the time the Halifax regulars gather again, at this time in 2020, the winner of next year’s election will be known. If it’s not Trump, great, the world can get back to its usual level of chaos. If it is—well. “Europe will say, ‘You’ve seen this guy. You know what he’s like. And you still want him?'” one conference participant said.

In that world, institutions that have been barely hanging on might start to unravel in a string of exhausted divorces. The G7 (which Trump is hosting next June at a venue to be named. Will he invite Russia?). NATO, which doesn’t get much love from its largest contributor. The European Union? The White House doesn’t get a vote, but who knows, maybe it sets a tone. I had four versions of the what-if-Trump-gets-re-elected conversation, started each time by somebody else, in the space of 36 hours, and I’m not a big schmoozer.

READ MORE: The knockout of Donald Trump looks as distant as ever

This is my third visit to the Halifax forum. Each time I find myself playing Rank-The-Threats. In 2014 Russia had just invaded Ukraine, and Stephen Harper had whipped out his CF-18s to attack Daesh targets in Iraq. My summary of that year’s forum doesn’t mention China. By last year, 2018, China was coming on strong, probably the main subject of preoccupation. Even Ukraine’s then-foreign minister, Pavo Klimkin, was spooked by China, although in contrast to Russia it was not formally, physically, invading his country. “Russia is in destroy mode,” he said then. “China is trying to create structures and rules.” In context, it was clear they were structures and rules Klimkin didn’t like.

This year, on the eve of local elections in Hong Kong and with a veto-proof Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act sitting on Donald Trump’s desk, China so dominated the early discussions that people who worry about anything else had to plead for the crowd’s attention.

“It’s interesting, no matter what panel, it always goes to China,” Gen. Rajmund Andrzejczak, Poland’s top soldier, mused during a panel discussion that was nominally about alliances among democracies. “But I’m from the centre of Europe.” And if you read NATO threat assessments, as he often does, “it’s absolutely clear. Number one, Russia. Number two, terrorism.”

If China had any competition for space in the forum’s nightmares, the competition was not so much a place or thing so much as an absence: the lack of a minimally coherent “we” that could serve as the subject of the sentence, “What are we going to do about China?” Or climate change. Or migration. Or assorted fundamentalisms (white supremacist violence was on the Halifax agenda for the first time, at one of nearly two dozen breakout dinners on Saturday night).

The “rules-based international order” that featured in so many Chrystia Freeland speeches over the past few years is increasingly hard to find. Alliances don’t thrive on stasis. They need leadership. The leadership that was assumed in the construction of so many alliances, especially the aforementioned NATO and G7, was that of the United States. And the current U.S. president is a random-event generator.

On Saturday, Navy Secretary Richard Spencer bragged to the Halifax crowd that he had not threatened to resign over Trump’s decision to reverse disciplinary measures against a Navy SEAL. A day later Spencer was fired for meddling in the same case and released something that read a lot like a resignation letter. He saw a conflict between a presidential order and the constitution, he wrote. He also wrote: “The rule of law is what sets us apart from our adversaries.” Well, yes, ideally. A succession of Trump administration officials addressed the forum. Perhaps one day we can contrast their reassuring comments with the likely language of their own eventual resignation letters, memoirs or testimony.

The weekend’s biggest uproar was over a panel on women’s contributions to global security that, in its original formulation, had four men and no women. It was an astonishing choice from an organization that runs a professional-development program for women in security-related fields and has spent four years trying to figure out its relationship with the Trudeau government, which pays close attention to gender balance. By the time the panel actually happened, it had been rejigged to include the political scientist Janice Stein and Jody Thomas, Canada’s deputy minister of defence. “We are not rare, shiny objects,” Thomas had written before the forum began. “We are here because we belong here.” It was a spectacular own goal on the forum’s behalf.

Everything was easier when Stephen Harper was the prime minister and Donald Trump was not yet the omnipotent six-year-old at the head of U.S. Republicanism. Before he died, John McCain’s arrival was the highlight of each Halifax weekend; the conference’s first edition in 2009 was a portal to an alternate universe in which he’d beaten Barack Obama for the presidency. The Arizona senator’s fondness for gunboat diplomacy was always debatable but these days it’s routinely discarded as an option, for different reasons, in both Washington and Ottawa. The premise of these conferences is that problems have solutions and that liked-minded western allies can agree on what those solutions should be. It’ll be a good thing if that’s true, but lately wishing doesn’t seem to make it so.