In the age of Trump, Canada triples down on the trade file

Canada now has three cabinet ministers working on the trade file. But history suggests escaping the U.S. economic orbit won’t be easy.

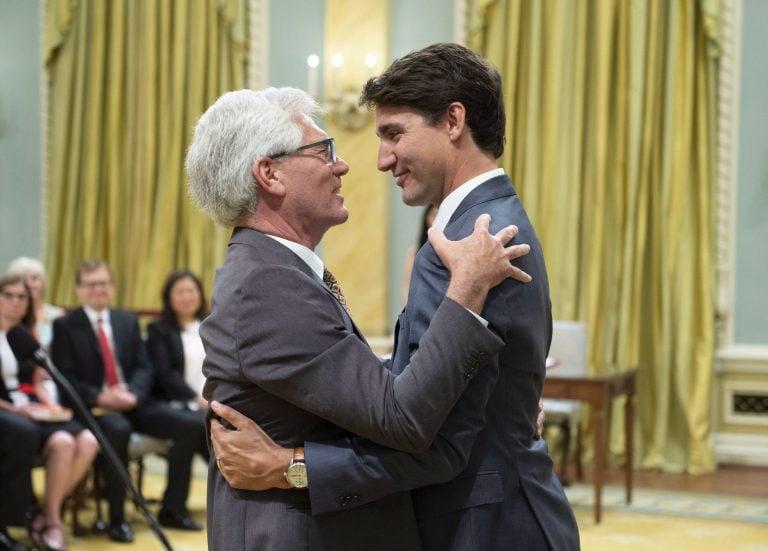

Jim Carr hugs Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after being sworn in as Minister of International Trade Diversification during a ceremony at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Wednesday, July 18, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Share

If the allocation of people is any signal of priorities, then trade is now the top focus for this Liberal government. Following last week’s shuffle, Canada now has three cabinet members of whose portfolios economic exchange forms a major part.

Foreign affairs minister Chrystia Freeland has spent a considerable portion of her time since moving up from the trade job in Washington, D.C., renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). But Wednesday’s shuffle hedged against U.S.-linked economic trouble, with former natural resources minister Jim Carr in the newly-renamed role of minister of international trade diversification while new entrant Mary Ng took the role of minister of small business and export promotion, with that last file a new addition to the title.

At Rideau Hall, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau noted that there’s a need for Canada to “ensure that we are not as dependent on the United States.”

Budget 2018 provided cause for concern about the government’s lack of emphasis on economic issues, says Brian Kingston, vice-president of policy at the Business Council of Canada. The document made little mention of how Canada planned to respond to tax cuts in the U.S., a choice he calls “surprising and shocking.”

Relations between the Trump administration and Ottawa hit a rhetorical low following the G7 summit earlier this year, and the prospect of reaching a deal on NAFTA any time looks remote. The U.S. and Mexico have reportedly been discussing a bilateral deal that would exclude Canada.

RELATED: How Canada’s NAFTA charm offensive hit a wall of confusion and apathy

But Kingston has since seen a change of tone. The addition of “diversification” to the trade minister’s title is symbolic, but an indication of seriousness, and it’s also positive that the job went to a “senior minister” in Carr.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau has also been talking about competitiveness more. “There’s a recognition that we do have a problem here, and things could get very, very bad, very quickly,” says Kingston, pointing to tariffs on autos or withdrawal from NAFTA as actions that Trump has mooted that would have serious adverse economic consequences for Canada.

RELATED: The Trudeau Liberals are failing to turn economic success into votes

Still, intent alone won’t lead to less reliance on trade across the southern border. “Good luck,” laughed one close U.S.-Canada observer, when asked about the government’s renewed diversification focus. The market just over the border has always been one of the biggest impediments to growing trade with places further way. It’s the “gravity model,” says Kingston. “Trade naturally will go to an economy that’s large and in close proximity to Canada.”

Diversification could take the form of selling more to existing non-U.S. partners. Ng said last week that with Pacific and European trade deals done, it was time to “help [Canadian] small businesses access those markets.”

Another tactic involves opening up opportunities on other continents via trade agreements. The current enthusiasm for such treaties goes back to the Stephen Harper government when the goal became to “sign as many deals as possible and see what happens,” says Jennifer Levin Bonder, a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto whose research includes the history of Canada’s trade diversification efforts. The agreement with South Korea is one example of a few that have yet to really pay off, a reminder that “trade diversification is a good idea in theory, but it’s actually a lot harder to make it happen,” she says.

More recently, Kingston points to November’s Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiation meeting in Danang, Vietnam, when Canada appeared to walk away from the deal after the Prime Minister chose not to attend a scheduled meeting of participating country leaders. That “caused a huge amount of concern in the business community.”

RELATED: The Liberal Party insider who saved the TPP trade deal

Canada did eventually move forward on the re-named CPTPP, and enabling legislation was tabled in the House of Commons shortly before the summer recess. The treaty takes effect when six nations accede to it. Kingston says it’s crucial for Canada to be among them, or “we will not benefit from the first-mover access that you get primarily into the very large and lucrative Japanese market.” Japan itself and New Zealand have already done so, and Carr insisted last week that Canada is “absolutely on track” to join them.

With the way forward on CPTPP clear, Kingston says China is the next obvious target for a trade agreement. “It’s an engine of the global economy, and has serious market access barriers that are problematic for companies and exporters,” he says. The Prime Minister did go to China in December, but formal talks on a deal did not begin as had been expected. Critics have opposed such an agreement based on China’s poor human rights record. Shortly after being named, Carr told reporters that he was hoping for “a continuing conversation that looks for the alignment of interests” with China.

Having three ministers with trade-related mandates is fine, but coordination is crucial, says Kingston, who used to work for the trade department. The government has a number of supports for exporters, but they don’t always work together well, if at all. Budget 2018 combined five such programs under the Trade Commissioner Service.

A lack of coherent economic policy around diversification has also scuttled previous pushes, Bonder says. In the early 1970s, the unfriendly policies of the Nixon administration as well a desire to disassociate from the U.S. stoked by the “violent images on TV” from Vietnam and domestic race riots encouraged Canadian cultural and economic nationalism. The levels of foreign direct investment entering the country was also viewed with suspicion. “The Americans were buying up absolutely everything, so [the fear was] that there wasn’t even going to be a country left to protect,” she says.

The result was a series of what Bonder calls “policy experiments,” such as the Canada Development Corporation and the Foreign Investment Review Agency. (The Liberals’ Invest in Canada organization is simply the latest example of this strategy). But businesses did not appreciate the government’s limits on foreign investment, and no industrial strategy was established to integrate the various efforts. There were plenty of “one-off things to appease various segments of the population,” says Bonder. “But it never really fit into a a larger scheme.”

Canada needs to have “a little bit more foresight” and “try to plan instead of just always reacting to the United States,” Bonder says. As far as the current round of diversification enthusiasm goes, it’s too late for that.